How to Steal a Surrealist Painting Surreally

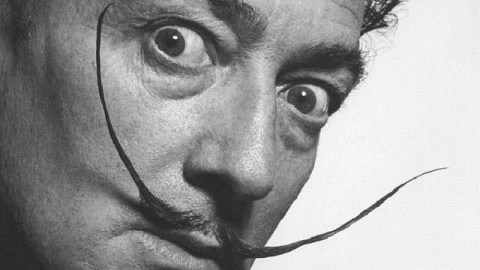

Art theft is a terrible problem worldwide. Aside from robbing the public of enjoying the great works of the past, art theft often leads to damage to the art and involvement with organized crime, who see great art with established monetary value as a readymade kind of currency. However, the recent theft of Salvador Dalí’s 1949 painting Cartel de Don Juan Tenorio on June 19th and its subsequent return on June 30th adds a fittingly surreal twist to the taking of a work by the arch surrealist (shown above). Not to condone art theft in any way and not to make light of breaking the law, but is it possible to see this caper as a work of art itself? Is it permissible to steal a surrealist painting surreally?

On June 19th, a thin, balding, Caucasian man approximately in his 30s and wearing a black shirt with white polka dots and dark pants entered the Venus Over Manhattan gallery in New York City carrying a black bag. (Some nice surveillance images here.) Venus Over Manhattan had only opened on May 9th and was still showing their inaugural exhibition, À rebours, a reference to Joris-Karl Huysmans’ experimental 1884 novel whose title translates from the French as “against the grain” or “against nature.” The eccentric aristocrat in Huysmans’ novel escapes the constraints of Paris’ conservative circles and begins collecting art—specifically exotic, often African fetishist art. The gallery gathered together 50 works that fit the “exotic fetishist” bill by artists such as Odilon Redon (the fictional character’s favorite artist), Henry Fuseli, Gustave Moreau, Jeff Koons, Glenn Brown, and Salvador Dalí. (A nice little “zine” accompanying the exhibition and featuring Dalí heavily is available online.)

Posing as a potential customer, the man began strolling about the exhibition. At some point, he pulled Dalí’s Cartel de Don Juan Tenorio from the wall, placed it in his black bag, calmly walked out of the gallery, and took the elevator down three floors to the ground floor and freedom. The theft baffled police until the gallery received an e-mail (from an untraceable address) saying that the painting was on its way back to the gallery. New York police seized the painting in customs upon its return from Greece and returned it to the gallery, who believe it is the original and claim that it seems to be unharmed, although the frame was not returned. The police still have no suspects and may never solve the case.

Is this a victimless crime? The gallery lost the chance to show the work for nearly two weeks, but they did gain a great deal of publicity from the crime. (I’m not saying that they orchestrated the whole thing for headlines, and neither should you.) The work itself seems to be unharmed by its Greek odyssey. As in all good unsolved mysteries, the question remains—“Cui bono?” I’ll argue that the art world does, in a small and, yes, surreal way.

A full-blown surrealist heist of a Dalí would feature a felon in a cumbersome, old-fashioned diving suit brandishing a lobster like a loaded weapon as he or she backed up to a window where a rope dangling from a hot air balloon shaped like a melting clock waited to carry the thief away. Surreal, yes, but hardly efficient—and easy to spot from a mile away. It would be like trying to steal a Magritte wearing only a bowler hat while threatening the gallery owner with your umbrella.

Just as feminist artist Roisin Byrne sees her thieving ways as a “parasitic” artistic response to the male-dominated art world, is it possible for us to see this theft as an artistic response to surrealistic art? What would that response be trying to say? Are we being asked simply to pay attention? Was the work taken from the gallery and returned (coincidentally?) on the last day of the exhibition a way of saying that its inclusion in the À rebours exhibition somehow demeaned Dalí’s art? At the very least, the low-key robbery and return goes against the grain of your everyday art crime and against the very nature of taking art for personal gain. Will copycats follow suit? Imagine an army of surrealist-stealing (and returning) criminals. I imagine that Dalí would approve.