Eudaimonism is False

My pals over at Bleeding Heart Libertarians are having an interesting conversation about the best justificatory foundation for their brand of classical liberalism. Kevin Vallier argues, correctly in my view, that “Utilitarianism is too consequence-sensitive and self-ownership is too consequence-insensitive.” Contractualism, he suggests, offers a third way that gets it just right in the consequence-sensitivity department.

Roderick Long replies by offering an alternative third way: an interesting version of eudaimonism that includes a not-overly consequence-insensitive version of the self-ownership thesis. Vallier responds by embracing eudaimonism himself, while countering that “the content of the virtue of justice is best specified by a contractualist principle rather than the self-ownership principle.”

I would like to intervene here to argue that both Long and Vallier are wrong because eudaimonism is false.

The eudaimonist says that eudamonia is the aim of life and the ultimate end of practical reason. Eudaimonia is often translated as “happiness,” but it’s better understood as flourishing or functioning excellently as the kind of thing one is. Acting in accordance with certain virtues is thought to be both instrumental to and constitutive of flourishing or excellent functioning. Both Long and Vallier accept a version of the unity of the virtues thesis, according to which the content the virtues can be fixed only by reference to the content of the others.

My trouble is that it is hard to make sense of eudaimonia within a Darwinian worldview, and that there is no good argument to the effect that eudaimonia, whatever it is, ought to be the aim of action.

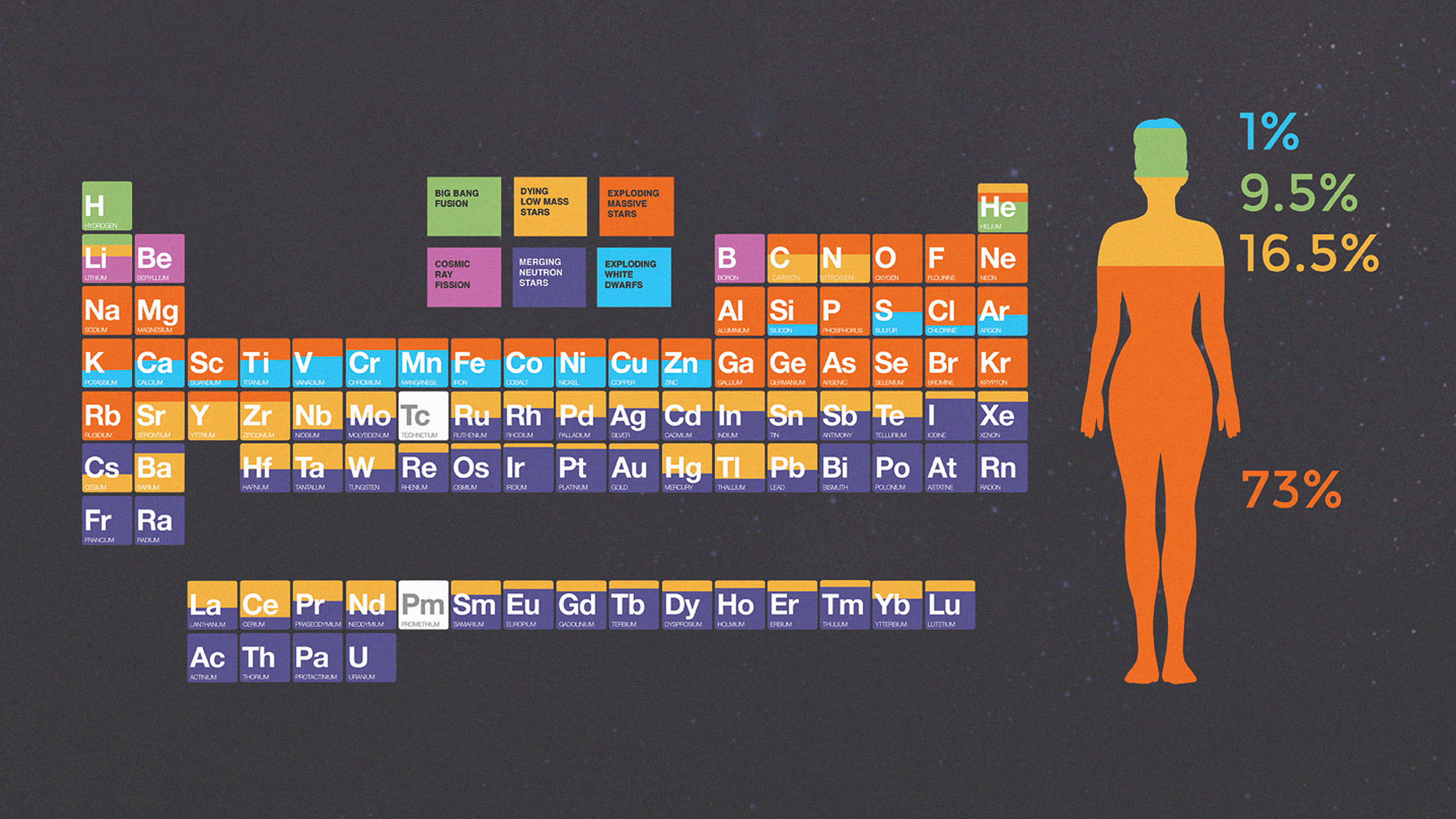

You are not an instance of a natural kind. You are a member of a genetic line. You have no essence. If you can be said to have a natural telos, it is to maximize inclusive fitness. But that is not only not in any sense a rationally mandatory aim, it’s a completely stupid aim. Making copies of your genome is, in an important sense, what you are for. But it has next to nothing to do what what you ought to try to do with yourself.

Relatedly, there is no non-stupid natural fact of the matter about what it would mean for you to realize or fulfill your potential, or to function most excellently as the kind of thing you are. Our potentialities are relative not only to individual biological make-up, but to culture and technology as well. Potential for mathematical or hockey greatness is meaningless in a world without mathematical notation or hockey. It may be that the world in which you have the greatest chance for really meaningful achievement and fulfillment, given your particular endowments, is one that does not yet exist. Bummer. What is means to function excellently in the here and now depends on the possibilities for functioning given the current cultural, economic, and technological dispensation.

Why not de-teleologize eudaimonia and stipulate that henceforth eudaimonia will mean “physical and psychological flourishing” or “good all-round health” or something wholesome like that? Good idea! But it’s hard to see this as an idea with normative teeth independent of the reasons we already have to seek good all-round health, or whatever. And we may well have reasons to do things that will keep us from really flourishing. What if you’re more interested in truth or beauty or justice come what may? What if you think a fixation on happiness and health is the enemy of art? With all due respect to Aristotle, I suspect philosophical contemplation isn’t really very good for people. But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth devoting your life to! Misery can be worth it! It really can be better to burn out than to fade away! Anyway, if I’m not making some huge mistake by saying “To hell with eudamonia!” which is, in fact, what I’m inclined to say about it–if it’s an aim one can choose to take on or not–then it doesn’t seem well-suited for foundational justificatory work.

Anyway, to say that utilitarianism is too consequence-sensitive is just to say that it is too everything else- insensitive–that it neglects values other than good consequences and it wrongly refuses to acknowledge the fact that we often have good reason to make decisions on the basis of other considerations, like fairness or beauty. To say that the principle of self-ownership is too consequence-insensitive is just to say that if we were to make it our single, supreme, indefeasible political principle, we’d screw over a lot of people and generally make a huge hash of things.

Why not this? There are a plurality of often competing values. There are a plurality of often competing reasons for action. What counts as a virtue depends on what you’re trying to do with your life and the kind of society you’re trying to do it in. I would suggest to Vallier that contractualism is the best framework for the justification of social morality and political institutions not because it hits the consequence-sensitivity sweet spot, butbecause pluralism is true, and contractualism, unlike the alternatives, doesn’t need it not to be.