Did Shakespeare Hold the First London Olympics?

If the Olympics are all about bringing the world together in one place to play, then William Shakespeare could be credited with holding the first London Olympics all the way back in the Elizabethan Age. The British Museum’s new exhibition, Shakespeare: Staging the World, which runs through November 25, 2012, gathers together nearly 200 artifacts related to Shakespeare’s writings that demonstrate just how the Bard brought the whole world to London, just as London itself entered the international stage as a major center of commerce and culture.

If any British artist belongs on Mount Olympus with the rest of the gods, it’s “Billy Shakes.” (Sir Paul’s a good, if distant, second, at least in my book.) Shakespeare love blossomed into Bardolatry sometime in the 18th century and continues to spread into every language and culture on earth. But before that globalization of The Globe’s in-house pen, Shakespeare himself spanned the globe through his imaginative reach and interaction with the hoards of travelers and traders that came to London. Just as Britannia began to rule the waves and colonizing much of the world, Shakespeare’s plays ruled the stage and reflected that reach of empire, but with the eyes and soul of a poet.

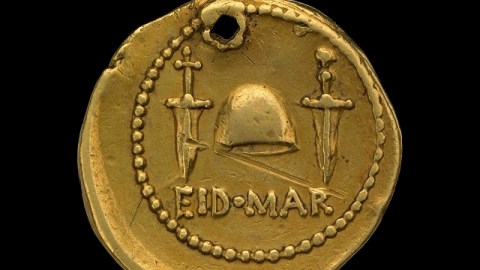

Many of the objects in the exhibition most likely were never seen by Shakespeare himself. The “Ides of March coin” (shown above) from 43 or 42 BC that commemorates the assassination of Julius Caesar (which Shakespeare dramatized in Julius Caesar, of course) brings the play alive in a way most high school English classes cannot. The daggers and cap of liberty shown on the reverse side symbolize the freedom of Rome from Caesar’s tyranny, proving that there were those who didn’t side with Marc Anthony, or at least the Marc Anthony who delivers the famous “Friends, Romans, Countrymen…” speech in the play. A portrait of Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun, Moroccan Ambassador to Queen Elizabeth I and head of a delegation of soldiers from Barbary, still has the power to fascinate and frighten. The ambassador came to London in 1600 on a state visit—a stranger in a strange land and perhaps the source for Othello, the noble Moorish soldier and tragic title character. As much as an international circus today’s Olympic London must be, the carnival atmosphere in Shakespeare’s day must have been even greater, especially before the modern technological conveniences that allow us to “explore” the world from our chair.

In addition to showing the outside world invading Shakespeare’s sphere, some artifacts give a sense of the rough and tumble Renaissance life. A rare sucket fork found during excavations of the theater district of Shakespeare’s time lets you picture a pubgoer downing sweetmeats with the forked end and lapping up the gravy with the spoon end in a hurry to make the curtain time. A bear’s skull found in the same excavations reminds us that the “high brow” Shakespeare we know today began as a very public entertainment in an area brimming over with brothels, beer houses, and bear baiting. The exhibition features many maps and drawings of London at the time, but it’s mementos such as the fork and skull that really strike home with the flavor and feel of the time.

If you’re lucky enough to be in London for the Olympics or any other time before November, take a break from the badminton and take in some Bard. The British Museum’s Shakespeare: Staging the Worlddoesn’t ask you to bow down in Bardolatry, but rather to see what the phrase “All the world’s a stage” might have truly meant to Shakespeare—the ultimate cosmopolitan in a world just learning what that word could mean.

[Image:Ides of March coin, reverse, 43-42 BC, gold aureus commemorating the assassination of Julius Caesar, Rome’s most famous murder and the subject of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. The reverse shows the daggers with which Julius Caesar was murdered and a cap of liberty to symbolize the idea of the liberation of Rome from Caesar’s rule. Lent by Michael Winckless Copyright of The Trustees of the British Museum.]

[Many thanks to the British Museum for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to Shakespeare: Staging the World, which runs through November 25, 2012.]