Why Giotto Is a Man of His Time… and Ours

If you ever find yourself in a bar that takes art history trivia bets, here’s a sure winner: Who is the only artist to be named by TIME Magazine as the person of their century? Smirk when they say Picasso. Laugh at calls for Michelangelo. Then collect your winnings as you whisper, “Giotto.” Named “Person of the 14th Century” in TIME’s 1999 end-of-the-millennium roundup, Giotto continues to make headlines seven centuries later. A new edition of Francesca Flores D’Arcais’ gorgeously illustratedGiotto and a new book by Julian Gardnerfocusing on Giotto and His Publics: Three Paradigms of Patronage demonstrate that Giotto’s art remains relevant today as it continues to give up its secrets, making the father of the Renaissance not only a man of his time, but also of ours.

Only 5 years separate the first and second editions of D’Arcais’ Giotto, but, as the author points out in her new preface, “[f]ive years can be a long time for a figure like Giotto, who is the focus of ceaseless research that continuously enriches our understanding of his art, and encourages reconsiderations of it.” An earth-shaking moment in Giotto studies came in September 1997 (practically the midpoint between D’Arcais’ two editions) when an earthquake damaged the interior of the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. In addition to repairing and stabilizing the frescoes, “[p]recise chemical and physical examinations were also carried out for the first time,” D’Arcais explains, that allowed scholars finally to unlock the secrets of the techniques that Giotto, Cimabue, and others used. Turning tragedy into triumph, restorers and scholars mounted scaffolds in the style and spirit of the original artists and saw the works as Giotto himself did so long ago.

Although the exciting details of these new developments outlined in the new preface will catch your attention, the stunning comprehensiveness and insightfulness from the original volume will make you linger over the master’s work. Instead of bowing to the legend of Giotto, first peddled by Vasari in his Lives, D’Arcais blames the legend for slowing our true understanding of the man and his art. D’Arcais replaces the otherworldly Giotto with a Giotto firmly set in his time and place, yet a radical both in his humanist approach via the Franciscan movement and in his approach to art itself in terms of both modeling and color. In fact, D’Arcais argues that “Giotto’s coloristic intuitions… make him a very modern, avant-garde artist.” The author backs up this claim by making great use of the more than three hundred illustrations, which give Giotto on the grand and the intimate scale. When we look at the colored shadows of a crucifix by Giotto in Santa Maria Novella, it’s easy to understand D’Arcais’ point and to connect Giotto across the centuries to the Impressionists and even Matisse. The already renowned, radically new three-dimensionality of Giotto’s art takes on a whole new dimension when D’Arcais calls the play of light and dark on a bell tower in the background of a fresco “a true Cubist exercise.” Just as the pictures themselves seem as fresh and new in the illustrations, the artistic sensibility of Giotto seems as modern and radical now as it was in the 14th century.

While showing you how Giotto changed the way painting looked, D’Arcais explains in words and pictures how Giotto changed the way that painting thought. By following the humanism of St. Francis of Assisi (my vote for “Person of the 13th Century,” even though TIME picked Genghis Khan), Giotto painted with “an extremely radical approach to everyday life” in which “he affectionately examined it in all its aspects, from the most aristocratic and sacred to the most humble and poor,” D’Arcais writes. Perhaps Giotto painted people so well because he understood and loved people so well. Nothing escaped his attention, from popes to plants. When grand theological issues threatened to disrupt his happy world, Giotto was “an attentive and sensitive interpreter of the most gripping theological and spiritual problems of his day,” D’Arcais explains, translating complex passages of religious text into compelling pictures more easily understood.

Giotto’s interpretive power is where Julian Gardner takes over in Giotto and His Publics: Three Paradigms of Patronage.Gardner,Emeritus Professor of the History of Art at the University of Warwick, echoes much that D’Arcais says, particularly about how Giotto’s legendary greatness has become “part of the mental furniture of the Renaissance” and how earthquake-related and otherwise restoration efforts have made it possible for “the moderately energetic scholar to study virtually all the works by or attributed to Giotto from the scaffold.” Where Gardner diverges from D’Arcais is over the direction that modern Giotto studies have taken. “Modern scholarship, like modern museology,” Gardner believes, “has actually distanced Giotto from us.” According to Gardner, a “radical decontextualization” that pervades modern Giotto scholarship “increasingly abjure[s] discussions of the artist in the round.” Gardner circles Giotto by looking at his paintings “through the prism of patronage.” Follow the money, Gardner’s reasoning goes, and you’ll find the truth.

Where others emphasize Giotto’s transcendence, Gardner centers his study on Giotto’s earthbound concerns, which are the same as any other working artist—doing good work and getting paid for it. In the century between St. Francis’ good works and those of Giotto the Franciscans went the way of almost all successful anti-establishment movements—they became the new establishment. The rising merchant class donated money to the Franciscans to allow them to build chapels and other monuments to the order’s new place of prominence in the Catholic church. “The speed with which huge new churches breached the urban skyline,” Gardner suggests, “perhaps speaks more eloquently of the economic strength of Francis’s primary constituency than its embrace of his imitatio Christi.” Gardner argues that the St. Francis of the Scrovegni Chapel looks more Christ-like as part of the Franciscans’ ideological shift away from advocating for the poor to accepting a position of power in the church.

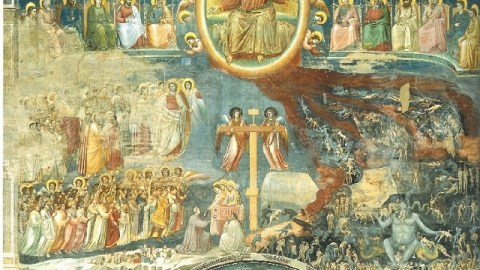

At the base of The Last Judgment fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel, Giotto paints the patrons handing over a replica of the chapel itself to the Virgin Mary (shown above). In the crowd of witnesses on the left, Giotto painted himself as an onlooker and, perhaps, approver of the transaction. As Gardner puts it, many of these merchants who grew rich by “ill-gotten profit” pursue “restitution… with the same perspicuity they brought to their prototypical capitalism.” In other words, the most fervent sinners became the most fervent believers and were willing to back it up with big bucks. Gardner excels in untangling the web of interests—sacred and secular—embedded in Giotto’s art. Knowing that such earthly concerns mixed with heavenly ideals back then just as they do today, Giotto the godlike treads the earth again and steps through the centuries into our own time with a fresh relevance. Gardner transforms Giotto from inert “mental furniture” into a vibrant, living artist once more.

Taken together, Francesca Flores D’Arcais’ Giotto and Julian Gardner’sGiotto and His Publics: Three Paradigms of Patronage transform the artist from someone we think we know to someone we want to know. After reading Gardner’s eye-opening critique, I’ll be going back again and again to the illustrations of D’Arcais’ text and looking for the hidden truths. Where Gardner will make you think, D’Arcais’ insightful aesthetic analysis of Giotto will make you feel. It’s a winning combination for any artist, in any century.

[Image:Giotto di Bondone. Detail from The Last Judgment fresco (ca. 1305) in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy.]

[Many thanks to Abbeville Press for providing me with the image above and a review copy of Giotto by Francesca Flores D’Arcais. Many thanks also to Harvard University Press for providing me with a review copy of Giotto and His Publics: Three Paradigms of Patronage by Julian Gardner.]