Who Is the Greatest Philosopher in American Art History?

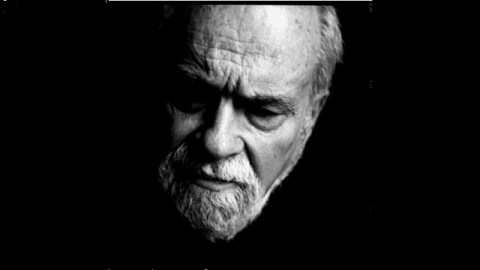

“Philosopher” is one of those job descriptions in America that brings inevitable jokes about unemployability. Carlin Romano’s new book, America the Philosophical, aims at transforming the Rodney Dangerfield of academic disciplines into a more respectable and surprisingly “American” enterprise. Romano argues that philosophy isn’t the epistemological navel gazing normally associated with the term but actually the everyday, pragmatic analysis that surrounds our every decision point. When it comes to the art world, Romano picks Arthur Danto (shown above) as the greatest philosopher in American art history—the man every thinking art lover has to read and every other philosophical critic needs to come to terms with in one way or another. Is Romano right? If not, who deserves Danto’s crown?

America the Philosophical operates from Romano’s central position that Americans don’t appreciate their own “philosophicalness” because it doesn’t look or feel like the philosophy inflicted upon them in that core requirement class they had to take in college. Instead, from Charles S. Peirce and William James on down, pragmatism has ruled the philosophical American day. Rather than Socrates, Americans have (unknowingly, according to Romano) followed Isocrates (“a man, not a typo,” according to Romano). Isocrates’ “vision of philosophy jibes with American pragmatism and philosophical practice far more than Socrates’ view,” Romano believes. “Indeed, he is the single intellectual of ancient Greece who incarnates the contradictions, pragmatism, ambition, bent for problem solving and getting things done that mark Americans… America the Philosophical operates under the sign of Isocrates. We simply haven’t heard of him.” With modern assists from philosophers Richard Rorty and John Rawls, Isocrates’ ancient pragmatic spirit has penetrated every pore of American society.

As wonderfully as Romano writes and argues, it’s difficult to acknowledge the influence of people almost no one has ever heard about. Romano concludes his case by calling President Obama as “both philosopher and cosmopolitan in chief.” “Overall,” Romano writes, “Obama’s most singular philosophical breakthrough was to project the cosmopolitan idea that the U.S. president must care about non-Americans” and even “think of other global citizens as constituents.” I wonder if Romano wants to change that last sentence in light of the recent craze for drone plane attacks.

Danto comes in where he uses philosophy to make sense of modern art, beginning with his early writings that helped explain Andy Warhol and Pop Art to the mainstream. Romano cites Danto’s “core subjects” as “the non-perceptual criteria by which we distinguish art from non-art; the necessary link between reasoned interpretation and art; the importance of understanding art, criticism, art history and philosophy as connected elements of an organic culture.” It’s that “organic” (i.e., pragmatic) approach that has separated Danto from the October set of Rosalind Krauss and others whose more classically philosophical art criticism makes my and many others’ brains hurt.

Romano effusively praises Danto’s essay titled “Post-Historical Period of Art.” “Post-historical, to Danto,” Romano explains, “meant post-narrative, because in an age of extreme aesthetic pluralism, ‘the master narrative of Western art is losing its grip and nothing has taken its place. My thought is that nothing can.’… But something could—smart essays of the sort Danto turned into his signature genre.” When art itself threatened to lose all meaningful connection to the world, Danto bridged the gap with his sharp mind and sharper prose. Danto eventually became “the one contemporary thinker about art that every intellectual interested in the subject had to read, the one critic simultaneously reviewing current shows and offering a broad aesthetic theory that explained both past and recent developments.”

I like Danto’s thinking, so I can’t really argue against his importance, but I think Romano shortchanges John Dewey’s thinking on art as a subset of Dewey’s ideas on education. Staying in the sphere of education, I think the ideas on art’s place in society promoted by Howard Gardner and Elliot Eisner are also significant on a pragmatic, policy-related level, although neither of them are “officially” philosophers, but Romano dubs plenty of non-philosophers philosophers in his book. In fact, every argument-loving, blogging American is a philosopher according to Romano. At the very least, Romano’s book will get a segment of the population thinking about thinking philosophically. Just starting an argument about who’s the best art philosopher in American history the way many argue over the best baseball hitter ever is a home run for Romano.