John Cage: Guiding Spirit of American Modern Art?

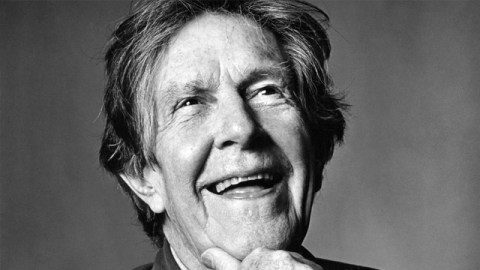

In 1951, musical composer and overall art theorist John Cage (shown above) stepped into an anechoic chamber at Harvard University. Touted as the quietest place on Earth, the anechoic chamber offered the chance for Cage finally to experience the silence he had been pursuing in his music. But rather than complete silence, Cage found himself bombarded with sounds he later learned were the workings of his own nervous system and blood circulation. Total silence, it seemed, existed nowhere. If sound was everywhere, then music was everywhere—and everything was music. That cognitive jump, combined with Cage’s explorations into Zen Buddhism, helped him spread his ideas to other forms of art, particularly the visual arts. That story and many others appear in Kay Larson’s beautifully written book, Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists. But did Cage really break new ground, or did he simply repeat what Marcel Duchamp and his readymades said decades before? That question weighs heavily on both Larson’s book and Cage’s legacy.

Larson, an art critic as well as a Zen practitioner herself, masterfully navigates the path Cage followed from simple beginnings to the complex simplicity of Eastern philosophy. Cage’s teacher D.T. Suzuki emerges as a paragon of Zen teaching and Zen living. Although I wish Larson had dove deeper into the intricacies of Cage’s music, she combines her knowledge of Zen and art to give a thorough picture of how Cage the musical theorist evolved into Cage the artistic theorist. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in the visual arts as well as Merce Cunningham (Cage’s life partner) in dance employed Cage’s ideas and followed his spirit. In Larson’s view, Cage stands at the center of the entire sphere of American modern art. “We notice that it was John Cage, not Marcel Duchamp, who first pointed artists in this direction” that led to Pop Art and Minimalism, Larson contends.

Larson lays it out simply: “This book proposes that John Cage originated the worldview that showed artists how to appreciate the work of Marcel Duchamp.” Calling Duchamp a “recluse” by the end of the 1950s who “most of the art world was determinedly ignoring,” Larson unfortunately knocks down Marcel to pump up John. “It was John Cage whose life touched multiple thousands of creative people in all disciplines, who performed—by himself, with others, and with Cunningham and company—around the world, and who was teaching and preaching nonstop,” Larson proclaims. “Cage had no need and no reason to sit at Duchamp’s feet like an acolyte… The prevailing art-world notion that Cage somehow took dictation from Duchamp is not supported by the evidence.”

When Larson says “prevailing art-world notion,” I wonder if she had the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Dancing around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp(which runs through January 21, 2013 and which I reviewed here) in mind. As the title suggests, that exhibition positioned Duchamp at the center of the circle of influence, with Johns, Rauschenberg, and Cage all having their own Marcel moments, direct encounters with the French master free of mediation. I wouldn’t say that the show presents Cage as an “acolyte” at Duchamp’s feet, but it definitely suggests Duchamp as the source of Cage’s ideas. “He used chance operations the year I was born,” the exhibition quotes Cage telling an interviewer after discovering Duchamp’s Erratum Musical.

But perhaps the question of who came first is irrelevant in the end, like original Zen question about the chicken and the egg. Larson’s writing about Cage, for whom she obviously has great admiration and affection, so she’ll naturally place him first. The PMA owns The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) and other major works by Duchamp, so they likewise naturally place him first, as does most of the art history establishment, who may still view Cage as primarily as musical innovator and only secondarily as a visual artist or influence on visual artists. To be truly Zen about the whole matter, you would say that it’s the ideas and not who delivers them that matters.

In the end, Larson’s Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists provides a fascinating new lens through which to see the whole course of modern American art. Where many see Pop Art as devoid of philosophy and purely as the use of the detritus of commercialism, Larson suggests seeing Andy Warhol, for example, as modern Zen master. The sometimes maddening lack of answers from the enigmatic Warhol thus becomes the strategic silence of the teacher of Zen desiring the student to discover the answer for him or herself. Warhol’s 8-hour film Empire (1964) capturing subtle changes in the Empire State Building in real time becomes an extended moment of Zen. As we continue to come to grips with Pop Art and its repercussions, Where the Heart Beats might hold some answers or at least propose new questions. The question of where John Cage and Marcel Duchamp belong in the messy mix of influence and who influenced whom, however, may never be convincingly answered, although it will remain an important one to ask and continue to explore.