How Daniel Clowes Reinvented Comic Books

“My earliest memory is of anxiety!” cartoonist Daniel Clowes tells an interviewer in The Art of Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist, the first serious monograph of the work of this seriously funny and seriously ambitious artist. Anxiety rules much of Clowes’ world, but it’s the anxiety that comes with questions of identity and belonging—all wrapped in a quirky and hilariously human package. “Unlike most writers and artists who take it for granted that human beings naturally seek each other’s company,” writes friend and fellow cartoonist Chris Ware, “Clowes seems to keep asking: What is it we really want from one another, anyway?” It’s Clowes’ complex technique matched with such deep questions as that one that lead at least one critic to claim that Daniel Clowes has reinvented comics.

Kristine McKenna lists Clowes’ themes as “longing, shame, loneliness, cruelty, and compassion,” which he handles with “a very light touch” despite their profundity. “That’s the great art part,” she adds. Clowes’ parents divorced when he was 2 (hence the anxious earliest memory), his stepfather died in a car accident when he was 5, and he had heart surgery in 2006 at the age of 45—just a few highlights of misery. Asked if he was depressed as a child, Clowes responds, “Not as a child—I got to that later.” “Later” meant the depressing experience of striving to become a working artist after graduation from art school. “I don’t think we’re in control,” Clowes muses. “I think it’s mostly random.” The closest Clowes comes to a secret to life is when he offers that “[l]ife is much easier when you’re only aware of your own little orbit and the injustices in that. Once you become aware of the global situation, as far as injustice, it’s almost too much.” Think locally, not globally, when it comes to wrong in the world, Clowes suggests, something that comes out in his often insular, but always intimate brand of darkly humorous analysis.

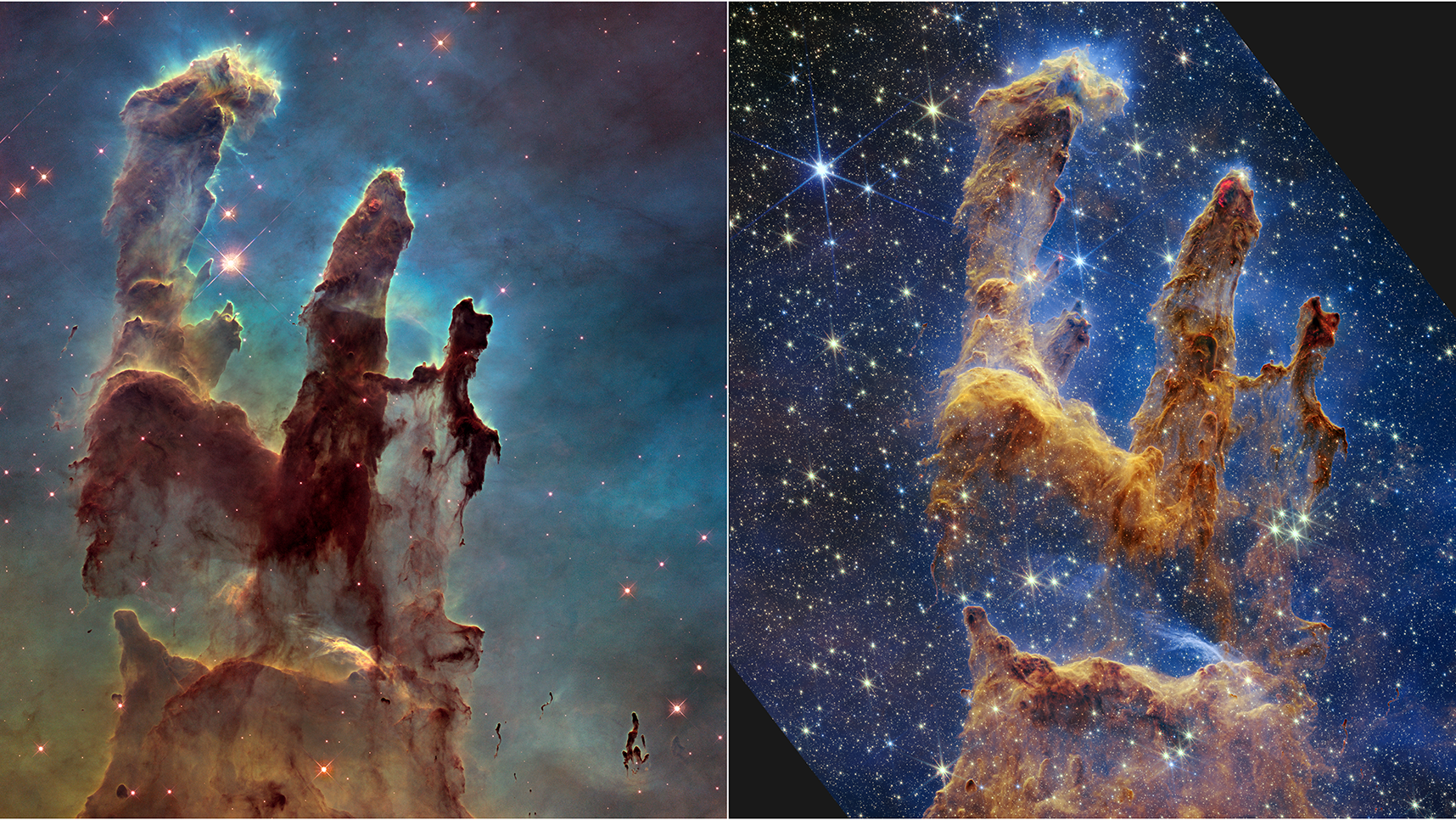

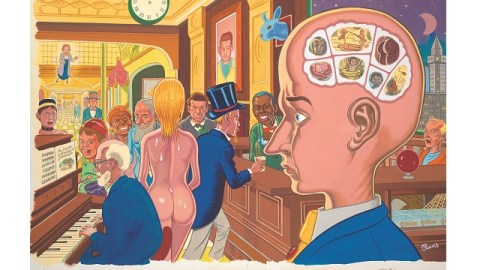

Eightball, which ran from 1989 through 2004, first showcased Clowes varieties of anxieties. The cover of no. 17 from August 1996 (shown above) looks like Clowes’ subconscious laid bare, complete with Freud himself at the piano. “Eightball is different…” Clowes wrote in a two-page advertisement for the series, “it might be a little bit scary at first… there’s some ugliness, gratuitous violence and weird sex… but stick with it…” In that free-form forum Clowes created a cast of characters grotesque yet familiar as versions of ourselves. Sex in myriad forms predominates in Eightball, but only to draw out the flaws of individuals and social mores in what volume editor Alvin Buenaventura calls Clowes’ “sardonic take on American culture.”

Almost all of Clowes’ major projects (Lloyd Llewellyn, Pussey!, Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, Ghost World, David Boring, Ice Haven, and The Death Ray) got their start in Eightball, which he stopped writing in 2004 to concentrate on such larger projects. Work on two film adaptations of his cartoons (Ghost World in 2001 and Art School Confidential in 2006, both directed by Terry Zwigoff) brought Clowes’ work to larger and larger audiences. But as Clowes seemingly got more “commercial,” he actually got more and more nuanced and mature. “What started as pleasingly manic chaos,” Chip Kidd writes, “has graduated into something more mature, bold, and sharply focused.”

Clowes’ Wilson and Mister Wonderful stand as his, so far, crowning achievements in the eyes of these critics. Ken Parille goes so far as to claim that Clowes has reached “the end of style” in a style-less style of sorts found in “[t]he narrative complexity of his post-Boring comics [that] works in unison with their highly accessible cartoony surfaces.” Using a generous helping of visual examples (the entire book is a feast of Clowes’ imagination on display as much as a catalog of his evolution), Parille shows you as well as tells you exactly how “[b]y the end of the post-Y2K decade Clowes had completely reinvented comic-book storytelling.” Big words, but Parille shows how Clowes can back them up, especially in the masterpiece Wilson. Clowes draws the title character in a variety of styles—all drawn from the visual lexicon of comic history stored in his head—so seamlessly you might miss what those differences are doing. “Each style communicates Wilson’s feelings about himself,” Parille believes. “Unknowingly, he becomes the visual narrator who inflects each page’s images with his thoughts and emotions at that moment.” Yet, Parille continues, “[d]espite Wilson’s many styles, there’s only one Wilson.” Clowes illustrates the very “paradox of identity” in which we’re constantly shifting yet still somehow “stable in our essence,” Parille explains. It’s deep stuff, but Clowes makes the comic medium seem the perfect outlet for exploring it.

In his hilarious tribute, “Who’s Afraid of Daniel Clowes?” Chris Ware writes that “[a]s does Robert Crumb, Clowes draws like nature,” while “[a]s did Vladimir Nabokov, Clowes writes like water.” Making Daniel Clowes sound like the odd love child of Crumb and Nabokov would make a great storyline for Eightball, but in the real world it works, too. The Art of Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist demonstrates in words and pictures just how central Clowes was and still is to the modernization of cartooning to the status of high art in a seemingly low-brow package. If you want to know what’s been happening in cartooning in the last 25 years—and what will be happening in the next 25—read The Art of Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist.

[Image:Daniel Clowes. From Eightballno. 17, August 1996. Copyright Daniel Clowes.]

[Many thanks to Abrams ComicArts for providing me with the image above and a review copy of The Art of Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist, edited by Alvin Buenaventura.]