Before Israel, the Jewish People Had a Socialist Utopia — in Siberia

Since the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 AD and their subsequent banishment from Palestine, the Jews had been without a national home until the founding of Israel in 1948. Right? Wrong.

The Soviets beat the Zionists by a few decades, and organised a Jewish Autonomous Region, improbably located on the Russian-Chinese border beyond Mongolia. Even more improbably, that region’s ‘Jewish’ status has survived stalinism, wars, deprivation and the fall of communism. But few Jews still reside in what was once billed as a future judeo-socialist utopia. Birobidzhan’s history remains, as one of the more bizarre footnotes in the struggle for a Jewish homeland.

“The Soviet solution of the national question is strikingly illustrated by the way the problems of the Jewish people have been dealt with in the Soviet Union,” writes D. Bergelson in ‘The Jewish Autonomous Region’, a English-language pamphlet published in Moscow in 1939, entirely written in socialist utopian mode. It describes how Jews, formerly oppressed by the Czarist regime, are now flourishing in the egalitarian Soviet Union:

“Jewish fliers took part in the historic expedition to the North Pole. Thousands of Jews operate machines in factories and mills. In the city of Gorky (formerly Nizhni-Novgorod), in which Jews were not allowed to live in the times of tsardom) there are about eight thousand Jewish workers employed in the automobile works alone. Among the prominent Stakhanovite workers we find many Jews like Blidman, Khenkin, Yussim and others, whose names are known all over the country. Jewish Red Armymen who took part in the battles at Lake Hassan were among those decorated by the Soviet Government for their heroism and devotion. Jewish names are among those of the Heroes of the Soviet Union, as well as among those of the Deputies to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and the Supreme Soviets of the Union Republics.”

One of the peculiarities of Soviet-style communism was the reality of having to deal with over 100 nationalities on the territory of the former Russian Empire. Not long after the 1917 Revolution, Moscow granted all of them a maximum of cultural and territorial autonomy (at least on paper). For the Jews, who had been a people without a country for 19 centuries, this was an unprecedented opportunity: “In addition to securing the Jews full equality, the Soviet Government has set aside a large district — Birobidjan — as a Jewish national territory. The Jews have thus acquired their statehood in the Soviet Union — the Jewish Autonomous Region, which is a unique and a most momentous development in the history of the Jewish people as a whole.”

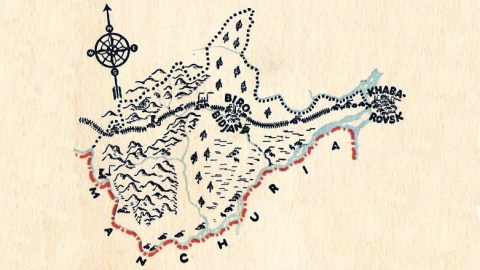

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast (in Yiddish: Yidishe Avtonome Gegnt) was created in 1934 within the framework of Stalin’s nationality policy, centered on the town of Birobidzhan, along the Trans-Siberian Railway, close to Khabarovsk. The settlement of the area (by Russians), under way from the middle of the 19th century, was greatly speeded up by the Trans-Siberian Railway (completed in 1916). The creation of the JAO was meant to counter both Zionism and (religious) Judaism by creating an atheist, Soviet version of Zion, and further to settle the still sparsely populated Siberian lands bordering China.

A more cynical view of the genesis and location of the JAO is that it would make it possible to deport the Soviet Union’s entire Jewish population to one of the remotest corners of the country. Initially, Jewish pioneers were lured to Birobidzhan by a concerted propaganda effort, ranging from posters and pamphlets to movies and books – one movie told the story of American Jews escaping the Depression to start over in the Jewish utopia.

As the number of settlers grew, Jewish culture in the region blossomed. Valdgeym, Amurzet and other Jewish settlements were established, the Yiddish-language newspaper Birobidzhaner Stern (‘Star of Birobidzhan’) was founded. But the growth of the JAO was cut short by Stalin’s purges before and after the Second World War, and by the war itself. The purges even led to the burning of the entire Judaica collection in Birobidzhan’s local library. In the decades following the war, many Birobidzhan Jews chose to emigrate; in 2002, Jews constituted less than 2% of the region’s 200,000 inhabitants (90% Russian, 4% Ukrainian).

Bizarrely, this has not prevented a Jewish renaissance of sorts: Yiddish is once again taught in Birobidzhan’s schools, there are Yiddish-language radio and tv programmes and the aforementioned Birobidzhaner Stern continues to publish a section in Yiddish.A new synagogue was opened in 2004, and there is a Jewish National University.There are extensive links between the region and Israel, which is the home country of Mordechai Scheiner, the JAO’s chief rabbi from 2002 to 2011. The rabbi is optimistic about the future of Yiddishkeit in Birobidzhan: “Today one can enjoy the benefits of the Yiddish culture and not be afraid to return to their Jewish traditions (…) Jewish life is reviving, both in quantity as in quality.”

—

This map is the cover of D. Bergelson’s pamphlet, which can be read in its entirety here at the Internet Archive. Many thanks to Thomas C Kneisley for sending it in.

Strange Maps #333

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].