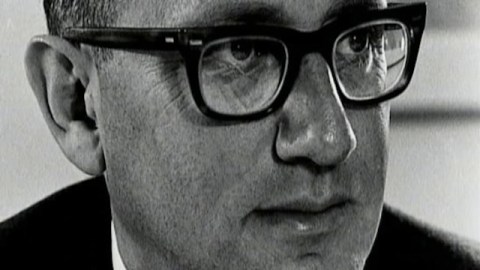

Kissinger’s Prescience

In Greek mythology, the gods sometimes punished man by fulfilling his wishes too completely. This is the first line of Henry Kissinger’s 1957 Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy. Always controversial, always compelling, Kissinger—according to the new Atlantic—is worth re-reading right now. What makes an old book newly relevant, or even sends it soaring—in scholar’s eyes, on syllabi, on Oprah? Wise writers and editors. Perhaps this old Kissinger can be our warm-up for Niall Ferguson’s biography of its author. Perhaps it can also convince key policy makers to think again on this issue.

Kissinger said many things we will remember. Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac. And, Each success only buys an admission ticket to a more difficult problem. And, In crises the most daring course is often the safest. These are all lines that state (what some would call) An Obvious Truth, then makes that truth elegant, epigrammatic. Kissinger’s mind is one we will study forever, but is it possible that the world’s current powers have shifted only so far as to make a book written fifty years ago a current must read?

Robert D. Kaplan’s “Living With a Nuclear Iran” recommends it. He writes:

At the time of his writing Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy, some analysts took Kissinger to task for what one reviewer called “wishful thinking”—in particular, his insufficient consideration of civilian casualties in a limited nuclear exchange. Moreover, Kissinger himself later moved away from his advocacy of a NATO strategy that relied on short-range, tactical nuclear weapons to counterbalance the might of the Soviet Union’s conventional forces. (The doctrinal willingness to suffer millions of West German civilian casualties to repel a Soviet attack seemed a poor way to demonstrate the American commitment to the security and freedom of its allies.) But that does not diminish the utility of Kissinger’s thinking the unthinkable. Indeed, now that the nuclear club has grown, and nuclear weaponry has become more versatile and sophisticated, the questions that his book raises are even more relevant. The dreadful prospect of limited nuclear exchanges is inherent in a world no longer protected by the carapace of mutual assured destruction. Yet much as limited war has brought us to grief, our willingness to wage it may one day save us from revolutionary powers that have cleverly obscured their intentions—Iran not least among them.

Kissinger apparently also said, We are all the President’s men. As a scholar, as an analyst, as a thinker and writer—Kissinger will remain one “we” look to when attempting to understand the global map’s never-ending puzzles.