What Procrastination Teaches About the “Parliament of the Mind”

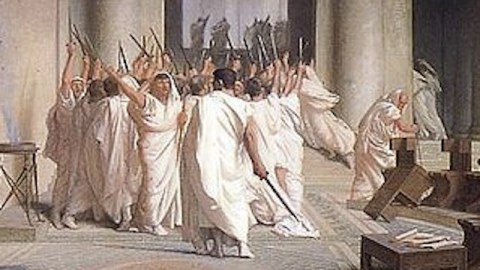

With all its inefficiencies, waste and contradictions, democracy may not be equal to our social problems. But it sure is a great model of the human psyche, as writers keep rediscovering—from Jay McInerney (“you are a republic of voices tonight. Unfortunately that republic is Italy”) to Steven Pinker (“our mental life is a noisy parliament of competing factions”) to Ian McEwan (“the mind could be considered as a parliament, a debating chamber. Different factions contended, short- and long-term interests were entrenched in mutual loathing”) to Philip Rieff (“reason was made a constitutional monarch, charged with […] appointing ruling parties to office from the parliament of emotions”). Yet what’s obvious to novelists and psychologists is invisible to any economist or philosopher whose theory depends on people being consistent and coherent. And despite all the recent hoopla over behavioral economics, that old-school idea still casts a pall—even on people who think they’ve left it behind.

It’s one thing to know, as James Surowiecki writes in his recent New Yorker piece on procrastination, that people should imagine their minds “not as unified selves but as different beings, jostling, contending, and bargaining for control.” But it’s hard to see the jostling factions as equals. Surowiecki’s piece illustrates that, too.

In the late 1970s, when I was a fledgling putter-off of things, shrinks at my college’s health center would lean into a reasonably serious suicide attempt or a sexual-identity crisis, but talk of undone term papers bored and annoyed them. Procrastination wasn’t considered very interesting by the sort of self-disciplined people who decide what matters in academia. Now, though, the subject is respectable (Surowiecki’s essay is a review of The Thief of Time, a collection of philosophical essays on the subject).

One reason is that more people than ever say it troubles them (quoting the University of Calgary’s Piers Steel, Surowiecki says four times as many people said they have procrastination trouble in 2002 as did when I was avoiding writing papers back in 1978). Second, the divided-soul feeling of procrastination (planning to do X but then doing Y instead) is a perfect testing ground for the sort of multiple-self theories have thrived in the social sciences over the past few decades.

Unfortunately, many of those theories don’t really depart from the old model of a single, unitary psyche. Though they declare that the psyche is a multiparty democracy, they aren’t nearly democratic enough. Instead of impartially examining all the mind’s factions, the experts favor only one. The part of the mind that plans to save for retirement? He’s the one who ought to be in charge. The part that wants to borrow money for a vacation? Bad news; let us figure out how to manage him.

In Surowiecki’s essay, too, only one of your multiple selves—the one that plans to lose weight by April, or start a savings account next week—is the real you. The others (the self who wants to eat potato chips for dinner or spend whatever you have at the moment) are enemies that undermine you. In that metaphor, the mind is not really a legislature composed of many factions; it’s a dictator wrestling with an insurgency.

The excuse for this point of view is that those impulsive, erratic other parts of the mind are bad for us; heeding them is “self-destructive.” This is the essence of many people’s anguish over procrastination: Why do I spend my whole paycheck, when I know I will be better off saving for retirement? Why, oh why am I smoking dope with my roommates, when I know it will give me less time to work on my history paper?

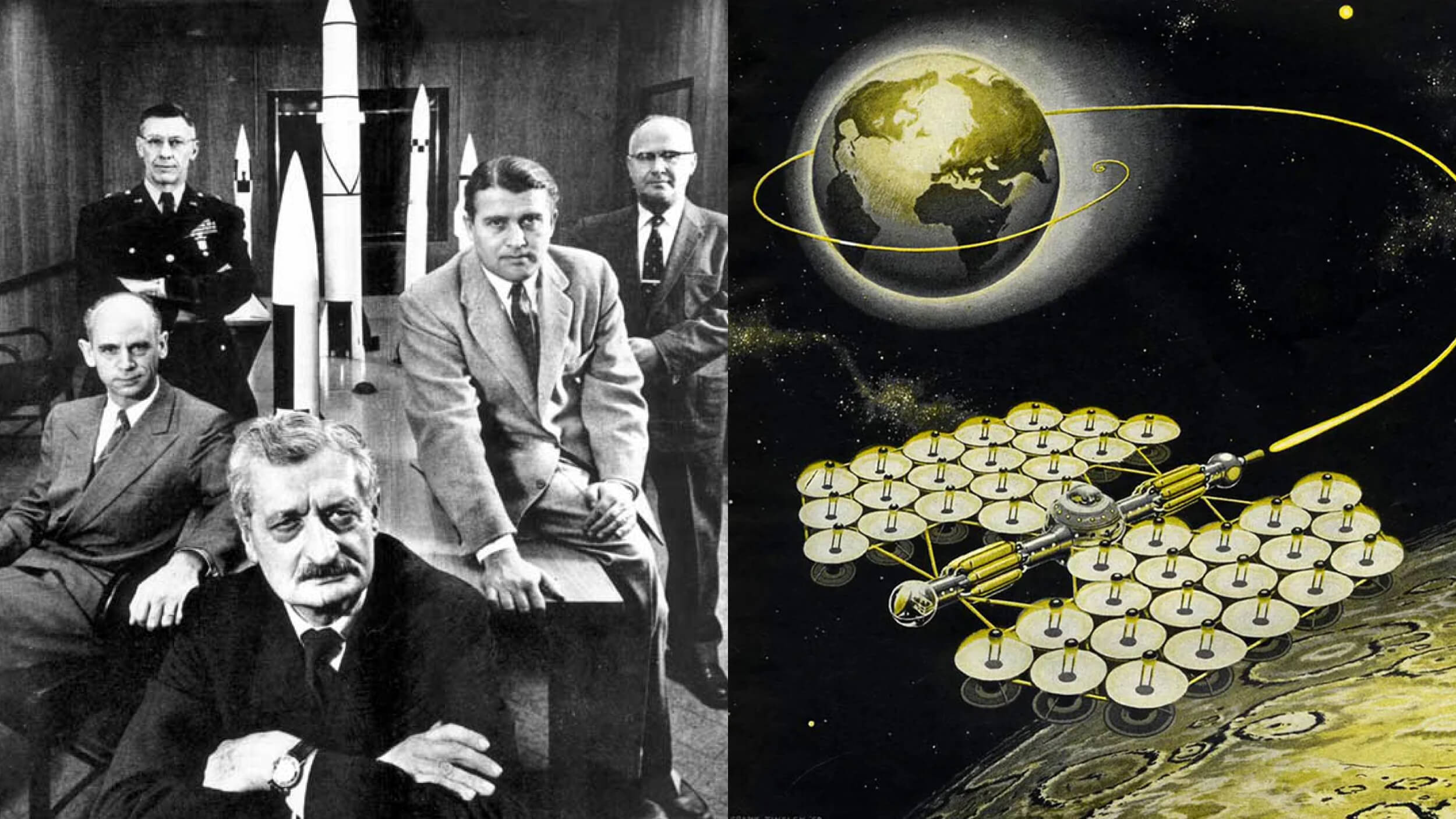

There’s not much proof, though, that the sensible, plan-ahead self is always right. After all, careful investing didn’t work out too well for Bernie Madoff’s clients, or these guys or millions of Russians who lost their savings in the early 1990’s. Over the years, they might have been better off spending every penny as it came in. Let’s face it: Disciplined planning for the long-term may pay off, or it may not. The answer will depend on political and economic forces that you can’t control.

As for the term paper, perhaps it’s not worth writing. When there is a gap between one’s plan and one’s conduct, it is sometimes the plan that’s the problem. For young people, especially, procrastinating on a goal is often the first step toward realizing it’s not really theirs—that they were paying lip service to other people’s notions of what they should do. In that case, “self-destructive” conduct murders a self they’re glad to see gone, a self imposed by others. Procrastination of this kind might be what James C. Scott would call a “weapon of the weak“: the laziness and disorder of slaves and serfs who had no appetite for their official chores.

I suspect that this phenomenon plays a role in Steel’s finding that far more people worry about procrastination today than did 25 years ago. The more the economy depends on services and information, the more meaningless deadlines and pointless obligations it creates. A subsistence farmer who puts of planting too long will starve, which prospect is a powerful motivator. On the other hand, consider a Web designer who misses the due date on some mockups for a redesign. What difference does that make, really? She turns it in late. Or she gets fired. Whatever; life goes on. Our conscientious and cooperative selves try hard to make these information-age demands feel as urgent as hunting, and as fell as death. But we have other selves within us, and they cry bullshit.

I am not arguing that the impulsive feel-good-now parts of the mind are more true or more right. I’m saying no faction in the mental parliament is invariably more true or more right. It doesn’t matter if you think your true self is the one that invests and plans and delays gratification (popular today) or if, in reaction to that culture, you’ve opted into the Romantic dream that the true self is the one that thinks “if it feels good, do it” (which notion had a good run when I was a kid in the 1970’s). Point is, you can’t understand what’s going on in your mental parliament if, like some meddling imperial power, you’re always rooting for one faction to win.