Dropping a Dime on the Questionable World of Art Prizes

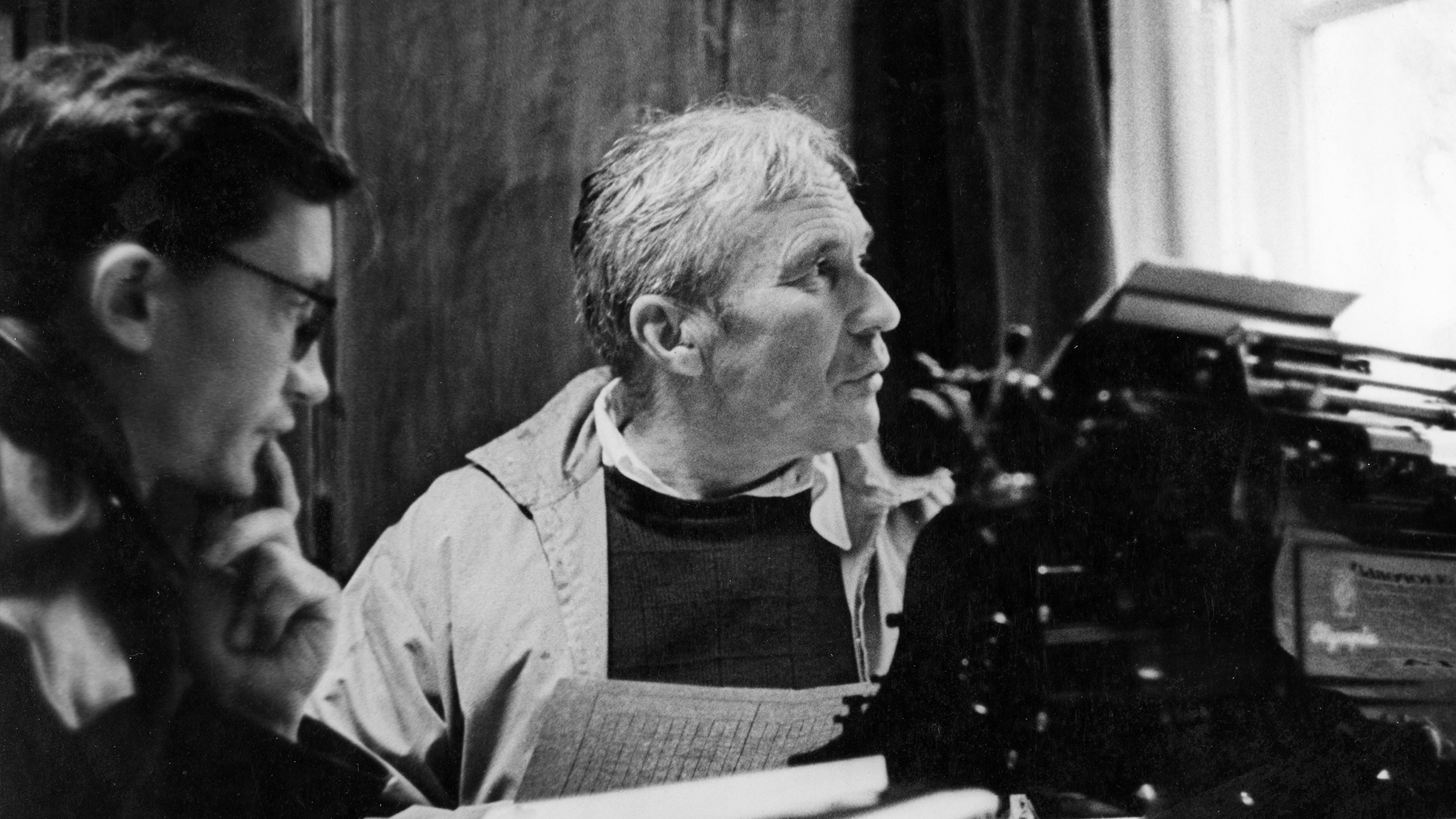

One of my favorite outdated slang phrases is “drop a dime,” which alludes to the days when a phone call still cost 10 cents and means to tell the truth about someone or something—essentially, to call them out. Last April, controversial Australian artist Richard Bell admitted that he picked the winner of the Sir John Sulman Prize, Australia’s most prestigious art prize since 1936, by tossing a coin onto a floor covered with artists’ names. The lucky coin landed on Peter Smeeth’s name, making The Artist’s Fate the winning submission. Bell (shown above, holding the now infamous coin) still refuses to apologize, claiming that “[m]ost artists know what these prizes are about. They’ve got very little to do with art and much more to do with the institution.” Ever the agent provocateur, Bell dropped a dime on the reality of art prizes with his coin stunt and started a new discussion of what the fate of art prizes should be.

Clearly a poor choice for solo judge in retrospect, Bell probably shouldn’t have been on any list of judge candidates for an establishment-supported art prize. When Bell won the National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award in 2003 for Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem), which bore the motto “Aboriginal Art—It’s a White Thing” (the title of an essay by Bell found here), he accepted the award while wearing a shirt saying “White Girls Can’t Hump.” (The shirt in the photo above reads in full: “Danger: Intelligent Black Man.)

In Bell’s essay on Aboriginal art, which he promises to be “conversational, playful, serious, tongue in cheek, moralistic, tolerant, sermonistic and informative,” Bell argues that “Aboriginal Art has become a product of the times. A commodity. The result of a concerted and sustained marketing strategy, albeit, one that has been loose and uncoordinated. There is no Aboriginal Art Industry. There is, however, an industry that caters for Aboriginal Art.” Similarly, Bell feels that the world of art prizes has become a kind of commodity in which the winner (and his or her gallery) finds instant fame and monetary success. “Like every prize, it’s a lottery,” Bell said in his defense. “’I couldn’t make up my mind so I did it by lottery.” Bell sees little fairness in the art prize system, so he simply inserted his own brand of antiestablishment randomness. In Bell’s eyes, all art prize judges pick based on some agenda, so he employed his own anti-agenda agenda in the form of a coin.

From Britain’s Turner Prize to the Golden Lions of the Venice Biennale, art prizes raise many more questions than they answer. As far back as the Lenaia of the ancient Greeks, in which Aristophanes, Sophocles, and other playwrights vied for top honors, a few have chosen to decide for the many what art is the best. Shut out of the awards doled out at the official Paris Salon, the artists known to us as the Impressionists created their own forum—the Salon des Refusés—to compete amongst themselves. Conservative establishments always hoped to hold back the tide of innovation in art by choking off all chances of publicity and profit—the immediate results of prizes bestowed. By tossing that coin onto the floor, Bell tossed something bigger into the eye of the tastemakers of the art world who dangle such prizes as a carrot to reward safe art and keep provocative art in check. Now that Bell’s dropped his dime, it’s up to the public to pick it up.