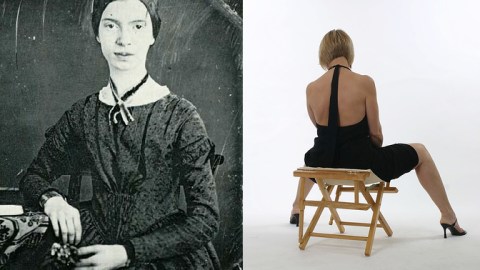

Emily Dickinson, Erotic Grief Counselor

Most people know that Emily Dickinson was a great poet, but it takes a deep plunge into her collected poems to realize just how staggeringly great she was. Usually represented in classrooms by a handful of brilliant but overfamiliar lyrics (“Because I could not stop for Death,” “There’s a certain Slant of light,” etc.), she wrote hundreds of poems of comparable quality, most of them within the span of just three or four years. During the years 1861–64 she produced, on average, a poem every two days, turning out masterpieces the way some people turn out diary entries.

This output is as much a neurological mystery as a literary feat, and I think it deserves an anniversary celebration. One hundred and fifty years ago, Emily Dickinson caught fire, and no poet—not even Rimbaud a decade later or Rilke in 1922 or Plath in the autumn before suicide—has reached quite the same degree of “White Heat” since.

The English language is such an unwieldy monster that truly mastering it seems impossible; most great writers are lucky just to tame it for a while. Not Dickinson: some of her poems are more interesting than others—she grew less radical as she aged—but she never really wrote a bad poem after 1861. Her ear, which seemed so eccentric to contemporaries, turned out to be nearly flawless. In her ability to verb nouns, noun verbs, scramble syntax, and mint a seemingly endless supply of original metaphors—all while exploring the outer reaches of intellect and emotion—she’s American literature’s best example of someone “thinking like Shakespeare.”

Like Shakespeare, too, she wears a permanent biographical mask. Who was she, really? Why did she stop leaving the house? Did she suffer from all the mental illnesses she’s been retrospectively diagnosed with—or some, or none of them? (“Much Madness is divinest Sense…”) What was her sexual orientation? One thing is certain: her life, romantic and otherwise, took place predominantly on the page.

Because misery loves company, Dickinson is the perfect poet to read when you’re in pain. Whatever kind you’re feeling—grief, anger, jealousy, loneliness—she’s felt it as intensely and can express it better. Not that she’s always healthy to read at those moments: like Kafka, she’s a paragon of neurotic martyrdom, of acquiescence to the “Geometric Joy” of our daily prisons. Where Walt Whitman provides ringing affirmations of hope, Dickinson’s poems counsel the voluptuous pleasures of “that White Sustenance – / Despair.”

Even so, there’s something sustaining and even indomitable about her vision. Here’s my favorite Dickinson story: after the death of the wife of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the literary editor and friend who infamously advised her against publishing her work, she sent him a letter containing a four-line poem:

Perhaps she does not go so far

As you who stay suppose –

Perhaps – comes closer – for the lapse

Of her corporeal clothes –

Who else would have the nerve to console a grieving widower by eroticizing death? And yet I can’t imagine a more mysteriously comforting sentiment to express in the face of such a loss. We don’t know how Higginson reacted to those four lines, but they get me every time.

Dickinson’s work as a whole is in that spirit: oblique comfort wrested out of agony. For all her self-proclaimed despair, she never did give up—never did commit suicide or stop writing extraordinary poems and letters. (As a master of the epistolary form, Dickinson is one of the great prose writers in English, although no one ever calls her that.) Making despair sensuous and luxuriating in it was her victory over it. You can argue that some of her suffering was self-inflicted, or pathological—but realistically, how many of her contemporaries could have understood such a bizarre genius, or given her the kind of companionship she craved? In the end she had to make do for herself, and she proved herself surpassingly “adequate”—one of her signature words—to the challenge.

[Images: literaryhistory.com, cltampa.com.]