Beyond Celebrity Adoptions

What’s the Big Idea?

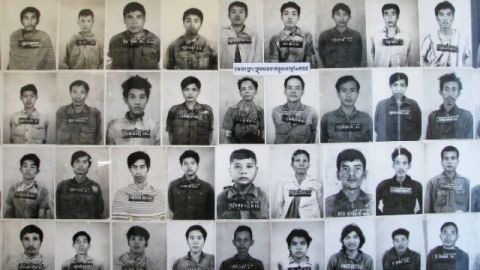

Three decades after the defeat of the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia remains socially and economically scarred– worse off in many ways than it was in 1960, when the country was an Island of Peace. Labor conditions are so wretched that many young women choose sex work over jobs in the booming textile industry.

24/7 the news stream spits out statistics like these: x thousand dead in Darfur, x hundred killed by a roadside bomb in Kabul. We’ve all read the meta-news, too: we know we’re being “bombarded” by media and that we’ve become “desensitized” to human suffering. We’ve seen the South Park parodies of Sally Struthers weeping, trying to convince us to sponsor this particular child, and of philanthropic celebrity adoptions that treat rescued children like a seasonal accessory.

How do we* get inside this? Graphic photos of atrocities? Guilt-inducing harangues from zealous missionaries? What, if anything, can move us to take the suffering of people outside our immediate families personally?

Compassion comes naturally to Sophal Ear – autobiographically, you might say. He owes the fact that he’s alive today to his mother, Cam Youk Lim, and, horribly enough, to the death of his father. When he was still a baby, the Khmer Rouge packed up his middle-class family and shipped them from Phnom Penh to a rice-paddy labor camp. Working long hours and subsisting on Khmer-issued rice gruel, Sophal’s father soon died from malnutrition and dysentery. While alive, he had been too weak to travel. His death freed Sophal’s mother to take advantage of Vietnam’s repatriation program, using her (very) limited Vietnamese to pass the border test and save the lives of her five children.

Fast-forward to now. Sophal is 36 years old. An assistant professor at the US Naval Postgraduate School, he researches, writes, and speaks internationally about post-conflict reconstruction, development, and growth, in particular, for Cambodia. He has worked for the World Bank, whose mission at the time was “to reduce poverty and improve living standards through sustainable growth and investment in people.” His life’s work is explicitly driven by gratitude to his mother for her sacrifices on his behalf, and compassion for people like his father who weren’t so lucky.

Sophal Ear: I got to Berkeley when I was 16. It was really an incredible experience. This is a school with a dozen plus Nobel Laureates. I understood then that I had a responsibility from having gotten into such a school to give back. . . and then to have the opportunity four years later to go to Princeton and get a Master’s Degree at no cost because I won a fellowship for that, that was the moment I decided that, if I do anything in life, I’d better work in international development and try to alleviate poverty, to try to help Cambodians, in particular. Whether politically or in terms of helping the economy – to give back because I certainly feel that from those towhom much is given, much is expected.

Powerful though his motives are, Sophal Ear is just one person. He can’t alleviate global injustice and economic hardship singlehandedly. A large part of his time, therefore, is spent motivating people who have led more or less comfortable lives to take human suffering personally. Like any good storyteller, Ear uses humor, generosity of spirit, and precise, often personal detail to bridge the distances between himself and his listeners. His personal homepage, for example, not only offers rich resources on the Cambodian genocide – it also invites you to share his passion for amateur photography.

Sophal Ear On Public Speaking:

When I describe my personal experience to audiences, I think that they can relate to the fact that I grew up poor, I was on welfare, I had, for example, an incident where

my Kindergarten teacher would send back a note through my backpack in France. And my mom would throw it away because she didn’t read it or she couldn’t read French. And then finally she was accosted and told that I wasn’t wearing underwear to school. And you know, it’s not a cultural thing . . . my mom said, “We don’t have money for underwear.”

And I think audiences generally relate to that when I say that it was “the case of the missing underpants.” Because it’s really how we were able to clothe ourselves that winter when the

teacher found, you know, collected from the community bags of clothes for our

family. That’s an experience that is not unique to me. Millions of people have undergone that. And audiences who haven’t should hear about that.

What’s the Significance?

The frequency and sophistication of advertising is increasing by the second. From every direction, messages cloaked in casual, friendly, story-like language attempt to cajole, seduce, or guilt us into action. Journalism, too, has become so politicized that we scan every article for subtext, for hidden intention. Like children, we’ve become highly sensitive instruments for detecting deception. Oversensitive, even, viz. this article (and subsequent retraction) about corrupt charities.

Good storytelling, sadly, isn’t enough anymore to penetrate our bristling defenses. The storyteller matters, too. Bono will not end poverty and war, however sincere he might be. What the world needs now – and just might be able to listen to – are humanitarian ambassadors like Sophal Ear, who have experienced atrocity and devoted their lives to doing something about it.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and Sophal Ear, not of the US Government.