OK, So Mitt Romney Despises Us. But Maybe Other Pols Do Too.

Shakespeare’s Caius Martius Coriolanus isn’t really suited to politics, but his family and friends urge him on, and so he makes a game effort at putting up with the smelly common people and their ridiculous electoral rituals, hiding his contempt. His tragedy hinges on the moment when he cracks and goes off-message—when he calls the electorate a “common cry of curs, whose breath I hate/As reek o’ the rotten fens, whose loves I prize/As the dead carcasses of unburied men/That do corrupt my air,” and (as Mitt Romney might say), so on and so forth, if you will. In this video Romney is now revealed as the capitalist Coriolanus. He talked too much, too often, in too many places about us miserable curs, and now we know him as the epitome of every boss-man we’ve ever hated. Clearly, there is something about this man that is unsuited to politics in a democracy. But this latest demonstration of his contempt for elections and the electorate has left me wondering if he’s really so different from other candidates. I wonder: Is Romney a terrible politician because he has these feelings of disdain that are unique to him? Or is it just that he’s failed to hide feelings that many politicians share?

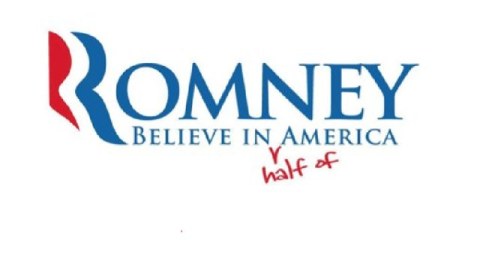

Granted, Romney’s contempt for people and institutions does seem extraordinarily vast and various. It includes workers banding together to protect their interests (speaking of “cleaning house” in the government after getting elected, Romney said “I wish they weren’t unionized, so we could go a lot deeper than we’re allowed to go” (that’s in part 2 of the Mother Jones videos, around the 6:45 mark). He laughs at the notion that diversity can add value to a group (at one point, Romney jokes that he’d have a better chance of winning the Presidency if his father had been Mexican, instead of an American born in Mexico (hard-de-har-har). And, now-famously, he shows contempt for people who aren’t like him: he said nearly half the population will vote for President Obama because they’re people who “are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it.” Where he goes on to say “my job is not to worry about those people. I’ll never convince them that they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives.”

I don’t buy the notion that this is a “real Romney” letting his hair down with his $50,000-a-plate bros. As Philip Bump pointed out over at Atlantic Wire yesterday, sucking up to $50,000-a-plate donors (by appearing to take them into the backstage of campaign strategy) is just as much of an act as sucking up to us unwashed masses. The attitude in the video strikes me as authentic because it does not differ from other versions of Romney. The candidate who once said “I’m not willing to light my hair on fire to try and get support,” the one who said “I’m running for office for Pete’s sake, I can’t have illegals,” is the candidate whose behavior in the Republican debates dripped scorn for his opponents and for the process itself. He’s transparently disdainful of the whole business of vote-seeking, as he explains elsewhere in the video: “Discussion of a whole series of important topics typically doesn’t win elections,” he says, before explaining that his campaign is in the hands of “a very good team of extraordinarily experienced, highly successful– consultants. A couple of people in particular who’ve done races around the world.” In other words: Getting elected involves a strange and distasteful set of procedures, I’ve got some guys on it. Like when we called the exterminator that time.

All in all, pretty insulting to us, the great American people. Yet I find myself wondering if Romney’s feelings are really rare among office-seekers. After all, anyone who has to respond to the needs of strangers, or who simply has to repeat the same thing over and over to people s/he doesn’t know, develops a certain weariness with human beings. If you’ve ever been a waiter, worked at a counter, canvassed door-to-door for anything, run the door at any sort of event, you will know what I mean. You begin by seeing individuals; inside of an hour you see types (who, annoyingly, don’t realize that they’re types, and that you’ve heard their jokes/whines/complaints/apologies before).

That’s generic to dealing with the public in any way. But there’s an extra stress in being a politician, which is nicely captured in Michael Lewis’ new piece in Vanity Fair about Obama: We want our leaders to do more than solve problems, and do more than merely sympathize. We want them to resonate to our emotions, embody them and reflect them back to us. That means high office as Lewis writes, involves “bizarre emotional demands. In the span of a few hours, a president will go from celebrating the Super Bowl champions to running meetings on how to fix the financial system, to watching people on TV make up stuff about him, to listening to members of Congress explain why they can’t support a reasonable idea simply because he, the president, is for it, to sitting down with the parents of a young soldier recently killed in action. He spends his day leaping over ravines between vastly different feelings. How does anyone become used to this?”

As it happens, there are researchers trying to answer that question. They’ve been at it ever since the sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild proposed the concept of “emotional labor”—the work of getting your own feelings to line up with the requirement of your job, so you can get others’ feeling what you need them to. To illustrate why this is work, Hochschild tells the story of the passenger on a long plane trip who asks a flight attendant to smile. “You smile first,” she says. He does. “”Good,” she replies. “Now freeze and hold that for 15 hours.”

Emotional labor often is studied in unprestigious jobs (Hochschild’s book discussed flight attendants, who have to be nicer than normal people, and bill collectors, who have to make themselves nastier than normal). But who has to do more emotional work than politicians? Is Romney the only one who, 15 hours into a typical campaign day, comes to resent the demands of the job, and therefore the common cry of curs who make those demands? I doubt it.