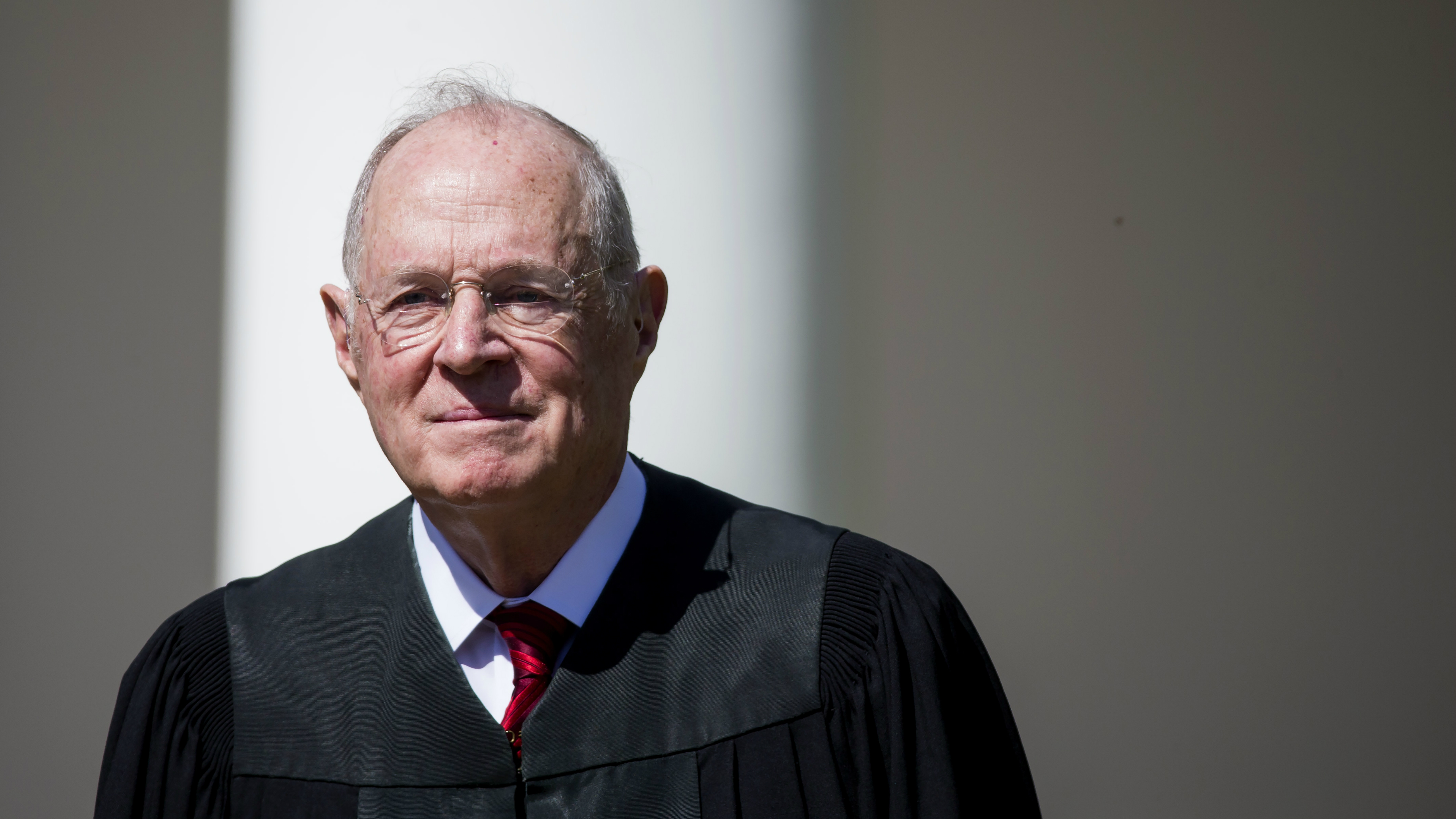

Affirmative Action is Up to Justice Kennedy

This is an edited version of a Praxis post that originally appeared on October 9, 2012.

We are hours or days away from a ruling in Fisher v. University of Texas, a case in which a white woman claims she was rejected from the university because of her race. Ten years after the Court ruled in Grutter v. Bollinger that the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection permits universities to consider race in admissions decisions, many think Justice Anthony Kennedy will cast the decisive vote ending affirmative action as we know it.

On the surface, this prediction seems like a safe bet. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, author of the Grutter decision, has retired. Her replacement, Justice Samuel Alito, is a strong opponent of race-based affirmative action, as are Justices Scalia and Thomas. Chief Justice Roberts has written that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” making an Affordable Care Act-style surprise very unlikely. Justice Kennedy dissented in Grutter, arguing that when the University of Michigan sought a “critical mass” of underrepresented minorities it “subverted” the “individual assessment” of applicants required by the Constitution.

It’s arithmetic, as Bill Clinton would say. We count five justices who have signaled a willingness to overturn Grutter versus three who seem certain to vote to uphold it. One justice, Elena Kagan, is not taking part in the case. That makes for a 5-3 decision ending racial preferences.

But the question mark in this calculus is Justice Kennedy. Though he voted against the University of Michigan law school’s admissions policy, he did not reject the school’s aim to enhance the diversity of its student body. In fact, he affirmed Justice Powell’s conclusion in Bakke v. Regents that diversity is a “compelling interest” for educational institutions. His problem with the Michigan model was what he saw as its crass means of reaching that diversity:

To be constitutional, a university’s compelling interest in a diverse student body must be achieved by a system where individual assessment is safeguarded through the entire process. There is no constitutional objection to the goal of considering race as one modest factor among many others to achieve diversity, but an educational institution must ensure, through sufficient procedures, that each applicant receives individual consideration and that race does not become a predominant factor in the admissions decisionmaking. The Law School failed to comply with this requirement, and by no means has it carried its burden to show otherwise by the test of strict scrutiny. (emphasis added)

Justice Kennedy’s assessment of the admissions procedure in Fisher will turn on whether he believes the University of Texas rejected Abigail Fisher on the basis of a genuinely individualized assessment of the merits of her application vis-a-vis those of other applicants. If he is convinced that race played only a “modest” rather than a “predominant” factor in her rejection, he may vote to uphold the school’s policy.

In other cases involving race and schooling, Justice Kennedy has struck a similarly moderate note. In a 2007 case focusing on student assignment policies to high schools in Seattle, he emphasized the inescapability of race in policymaking considerations: “In the real world, it is regrettable to say, [colorblindness] cannot be a universal constitutional principle.” Basing student placement on race alone is wrong, he argued, but a variety of alternative strategies to deepening racial diversity are consistent with the 14th Amendment:

School boards may pursue the goal of bringing together students of diverse backgrounds and races through other means, including strategic site selection of new schools; drawing attendance zones with general recognition of the demographics of neighborhoods; allocating resources for special programs; enrollments, performance, and other statistics by race. These mechanisms are race conscious but do not lead to different treatment based on a classification that tells each student he or she is to be defined by race, so it is unlikely any of them would demand strict scrutiny to be found permissible.

This passage shows that Justice Kennedy is sympathetic to the goals of those who seek diversity in higher education, but it does not (by itself) provide evidence of his willingness to uphold the Texas admissions policy. Kennedy will join the Court’s four stalwart conservatives in insisting that the University of Texas’s use of race in admissions must pass strict scrutiny — the toughest test of constitutionality, requiring that a classification by race serve a compelling government interest through narrowly tailored means. Kennedy will likely find that Texas meetsthe first test of strict scrutiny — the compelling interest prong — and focus his analysis on the details of how exactly the University considers race in admissions.

If he compares the two admissions policies, Kennedy should find that admissions decisions at the University of Texas use race less often, less directly and more modestly.

First, the race factor is operative for only 25 percent of the application files; the other 75 percent of applicants are admitted under Texas’s “Top Ten Percent Plan,” a race-neutral scheme devised in 1997 to increase campus diversity. Under the plan, the University accepts every student graduating in the top ten percent of his or her class, offering admission to many black and Latino students coming from high schools where these races represent a majority of the student body.

For those 25 percent of students who gain a spot outside the Ten Percent plan, Texas considers race as one factor among many to further enhance diversity. According to the brief of respondent filed by the University of Texas, race plays a “modest” role in admissions decisions and “race is considered only in an individualized and holistic fashion.” The University’s brief, in a not-so-subtle attempt to speak directly to Justice Kennedy’s central concerns, uses the word “modest” 17 times and “individualized” 29 times. Here is exactly where race fits in:

Race is one of seven components of a single factor in the PAS [Personal Achievement Score], which comprises one third of the PAI [Personal Achievement Index], which is one of two numerical values (PAI and AI) that places a student on the admissions grid, from which students are admitted race-blind in groups. In other words, race is “a factor of a factor of a factor of a factor” in UT’s holistic review. (emphasis added)

Viewed in this light, the place of race in admissions decisionmaking seems “narrow” indeed. The question, as the Petitioner’s brief points out, is whether the policy is too narrow: whether it is adequately “tailored” to the goal of increasing campus, and classroom, diversity above and beyond what the Ten Percent rule achieves. Emphasizing the modesty of the admissions policy’s use of race too heavily risks demonstrating that the policy does very little at all to enhance racial diversity.

This is the irony of both sides’ positions, and it is the delicate dance we will witness in the Supreme Court’s chambers sometime in the next few days.

Follow Steven Mazie on Twitter: @stevenmazie