The Real Heroes and Villains in Comic Books

Good versus Evil will always be the stock and trade of storytelling, especially in comic books. The skill of separating good guys from bad comes early to readers, with the occasional antihero appearing as an interesting change of pace. Behind scenes of these imaginative creations, however, many of their flesh and blood creators fight a never-ending, just slightly less Manichean battle for truth, justice, and an equitable share of the profits denied to them by the corporate comic publishers. In Comic Book Babylon, Clifford Meth chronicles the struggles of comic book creators of the past fighting against Marvel Comics and DC Comics for royalties and, just as importantly, recognition. In the midst of this often life-and-death struggle for aging artists, Meth separates the angels from the demons and uncovers the dirty realities behind the comics’ fantasy industry. Meth’s raucous, passionate, no-holds-barred style will leave you looking at comics and the corporate giants they’ve spawned with new eyes. Forget Superman. Forget Doctor Doom. Here are the real heroes and villains in comic books.

As most comic fans know, the story of the first comic superhero is also the story of the first comics creators getting ripped off. In 1938, artist Joe Shuster and author Jerry Siegel, fresh out of high school, signed away the rights to the multi-million dollar property Superman for $130 and set the stage for decades of corporate profits and their own slow decline into poverty. Not until the 1970s did an organized movement win them recognition and long overdue financial compensation. (Brad Ricca’s Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster—The Creators of Superman, which I reviewed here, tells their story in precise, troubling detail.) Comic artist Neal Adams spearheaded the campaign for Siegel and Shuster’s rights by using his considerable influence in the industry. When Meth found that his friend, comic artist Dave Cockrum, faced mounting medical bills and few prospects for new work, he called on Adams, a true comics hero, for advice and support.

Cockrum broke into the comic business writing fan letters, sending cover suggestions, and publishing in fanzines even while serving in the Vietnam War. Cockrum’s greatest claim to fame rests in his X-Men characters Nightcrawler, Storm, and Colossus. When those characters began to hit the big screen and make the big bucks, Cockrum received nothing as his diabetes took its toll on his health and finances. In rushed Meth, Adams, and others from the comics community heroically not just to help Cockrum, but also to set a precedent for other struggling comic creators to follow in fighting for their rights.

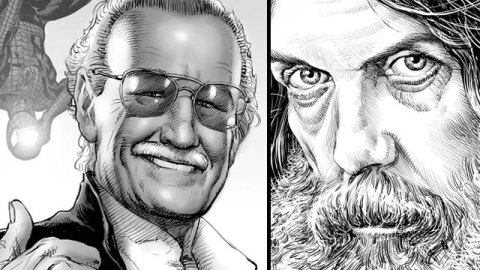

“Neal and I agreed that the first approach was gathering as many comics creators as possible for a fundraiser,” Meth writes. “[W]hile the Cockrums could certainly use the money, we’d be simultaneously spreading the word and gathering support for what would, of necessity, become a publicity war. We could never beat Marvel in a courtroom—that was their domain.” Facing down the corporate colossus, Meth and his cohorts decided to put Dave Cockrum’s face (reproduced in the book in Michael Netzer’s portrait that gracefully captures the artist’s kindness and gentleness) on the problem for all the world to see and judge.

Meth manages to put a face on the faceless corporation as well by slyly shining a spotlight on Marvel artist and editor Joe Quesada. Quesada’s dismissal of Dave Cockrum’s work as too old fashioned to run today initially raised Meth’s ire. But Quesada’s stonewalling over Cockrum’s rights really brought out Meth’s sharpest rhetorical knives. He faintly praises Quesada as “probably a very nice man” who “doesn’t spit in the soup,” as the old Yiddish expression goes, before striking a different tone with “But Joe Quesada is an honorable man” after Quesada tells Neal Adams he was doing everything he could for Cockrum. Like Shakespeare’s Marc Anthony coming not to praise the slain Caesar, but to bury him, all while harping on how Brutus is “an honorable man” until the mob turns the statement into a question, Meth buries Quesada and those siding with corporate interests over basic humanity under a landslide of snark. Maybe Quesada’s not the villain, but he’s surely not the hero.

Against the backdrop of this sad struggle, Meth presents the pantheon of modern comic book creators from an insider’s point of view. Stan Lee, the long-time face and voice of Marvel Comics as well as the co-creator of Spider-Man, the Hulk, the Fantastic Four, Iron Man, Thor, and X-Men, seems like the ultimate company man, but even he’s sued (and lost to) Marvel. In an extended interview with Lee, Meth gets at the creative mind and soul beneath the beaming, “Excelsior!” exuberance (captured, again, perfectly by Netzer’s portrait, shown above). Asked to name his favorite Marvel characters, Lee answers with the obvious Spider-Man but also with the more interesting Silver Surfer. “I got more philosophy into the Silver Surfer than anything I ever wrote,” Lee confesses. “He was always giving his opinions about life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness… I think those 17 issues of Silver Surfer that I wrote and that John Buscema drew are the best 17 comics that have ever been done. They’re classics.” Likewise, Alan Moore (drawn by Netzer above), the mysterious mage behind Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comes off in his interview as less mysterious but far more interesting and intellectual than comic books, their fans, and their creators are usually given credit for.

The tragedy of the slow, senseless decline of this league of extraordinary gentlemen (and gentlewomen, as Meth includes the stories of women comic artists Paty Cockrum, Dave’s wife, and Marie Severin) often overpowers the victories won for these artists. If you’re a fan of comic books and their history, this book opens a door into a world quickly disappearing (which includes the occasional party neatly summarized as “three kegs, two girls, and one fat lip”). In a final, “tribunal” section, Meth renders his final verdict on comic books. After remarking that “that ship has sailed” on the future of comics, Meth reveals why he wrote Comic Book Babylon. “Eventually, you hope the kid reading Batman pulls aside the curtain and sees the guys pulling the levers,” Meth writes. “This book commemorates the people I interviewed over the years. It’s a time capsule.” Unfortunately, it’s a time capsule with still living, breathing people trapped inside.

Dig deep into Comic Book Babylon’s darkness, however, and you’ll find a glimmer of hope. Just as Meth’s dark, often disturbing fiction (which I once reviewed here) can strike a humanist note if you listen closely enough, his advice to true believers will restore your faith in comics, heroes, and people. “Want me to share a lesson?” Meth offers. “Try this: When you admire someone’s work, tell them. A letter, a Facebook message, a beer if you see them slumped at the bar at a convention… People appreciate being appreciated.” Secondly, “Don’t cheat people… And buy art. Art is nice. Buying art supports artists, especially if you buy it from them.” Do unto others, especially if you like their work. Support the creators who made you believe that a man could fly, that the underdog had a fighting chance, that the good guys and gals win in the end, even if everyday truth says differently. Hope, as Emily Dickinson once wrote, is “the thing with feathers,” but it’s also the character in the cape racing to save the day. Comic Book Babylon by Clifford Meth will have you believe again that good people can fly in the face of corporate evil and win the day.

[Image:Michael Netzer. (Left) Portrait of Stan Lee. (Right) Portrait of Alan Moore. © Michael Netzer.]

[Many thanks to Aardwolf Publishing for providing me with the images above and a review copy of Comic Book Babylon by Clifford Meth.]

[If you’re interested in joining the fight for comics creators rights, consider contributing to Hero Initiative: Helping Comic Creators in Need, The Dave and Paty Cockrum Scholarship, or any other way of saying thanks to these talented men and women.]