Embrace the Noble and Well-Intentioned Ignorant

“Every day I live in mortal fear of offending someone.”

An old friend of mine tells me this over dinner. He shouldn’t have to be afraid. He’s not bigoted or intolerant. To the contrary, he’s inclined toward broad-minded attitudes.

But in his job, he comes into contact with a range of different people, many of whom are younger, and have lifestyles, argot, and attitudes that he might not know much about, unless he can grit his teeth through a dismal episode of “Girls” or whatnot. And there are only so many hours in the day.

My friend worries that he might stumble into the thicket of a debate that he didn’t know existed over nomenclature in the mercurial world of identity politics; that he might casually articulate a belief now superseded by a shinier new one; or perform a once-polite gesture, now deemed offensive.

Were this to happen, it wouldn’t be because he intended to hurt someone or to express intolerance, hatred, or contempt. It would be, quite simply, because he was ignorant.

Can you be ignorant today without being offensive or—that catch-all pejorative—inappropriate, in your heart?

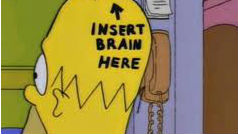

As a term, ignorance certainly accommodates a value-neutral meaning. The OED defines the ignorant, first, as those “destitute of knowledge.”

In elementary school we’d occasionally insult someone by calling them an “ignoramus.” Actually, this term has somewhat value-neutral origins as well. It comes from 16th-century jurisprudence. A Grand Jury would use this term to describe an indictment for which they found insufficient evidence.

It’s the fifth definition of “ignorant,” with more recent examples, dating from 1886 onward, that carries a stronger charge of judgment. Here, ignorant means “ill-mannered” or uncouth. This meaning of ignorant seems to prevail today.

Ignorant is now loosely synonymous with unkind, bigoted, malicious, or intolerant. A state of not-caring is gleaned from a state of not-knowing.

This is unfortunate. When people don’t know about another person’s job, lifestyle, preferences, religion, or culture, they have what I think is a natural human impulse to ask a question. From a position of noble and well-intentioned ignorance, they might be curious to learn.

As someone who identifies as a feminist, people have asked me all sorts of “ignorant” questions. They’ve asked if I didn’t think that women really regret not having children, or if feminists aren’t just unfairly hostile toward men. True, these questions embed opinions, and opinions that I disagree with. But even in these situations, I didn’t assume that the speaker was asking to hurt my feelings. I assumed that he was ignorant, in the most agnostic sense of the term, and seeking to be less ignorant by the act of asking a question, and assuming that it would be met with something other than the miffed rebuttal, “That’s Ignorant.”

This is tedious work, I know. Who wants to explain to people why they wear a headscarf, why they like guns, or how they feel about the name “Redskins?” We all want to be transparently understood by others, without having to educate, share, or build social understanding.

But building casual social understanding and good will is the nuts and bolts work of a democracy.

What’s even worse than having to “represent” for your people—which is the price one pays for having people— is that the nobly-inspired ignorant ask questions much less frequently today.

My friend is right to be afraid. One of the basic circulatory systems of democracy—the free exchange of attitudes and information through public conversation and social contact—is clogged up by the assumption that ignorance of another person’s beliefs, culture, or lifestyle signals malice, and therefore simply cannot be displayed.

If liberals sensitive to identity politics are afraid to ask ignorant questions, then other factions are proud not to. They seem to embrace unrepentant ignorance as a virtue. They give up on trying to understand, or to learn, entirely. In the anti-intellectual backlash of our times, they rehabilitate ignorance as a principled stance, on matters ranging from homosexuality to embryology to climate change and evolution.

Ignorance, in its most useful forms, acts like the ipecac syrup of intellectual culture. It gets things moving, even if noxiously, and eventually provokes understanding, which makes us feel better. When a culture doesn’t allow people to be dumb, even as more of us are dumber than ever on most topics, if only because the sheer number of topics seems to have exploded and gotten more fine-tuned, then the state of being ignorant goes underground and becomes almost a political subversion, a proudly-declared political stance. This is not good.

So, give a hug or at least a gracious helping hand to the noble, well-intentioned ignoramus today.