How to create an “idea generation assembly line”

- Main Story: Investor John Huber’s answer to the problem of generating great ideas consistently is simple: write more, and more often.

- Huber contrasts the art world’s highly selective approach to creative output with the arena of idea generation, the core of investing, where volume is king.

- Also among this week’s stories: Humanoid robots, the long-term thinking of Kevin Kelly, and the (com)pounding engine of success.

The investor John Huber posted a smart essay earlier this month about a recurring theme in this newsletter: how to consistently generate good ideas.

John’s answer is simple: write more — and get more reps in. “The more I write, the more I think,” he says. He continues:

Key quote: “I once heard that the difference between the great photographers and the average ones are that the great ones take average photos just like everyone else, they just never show those ones to the public, whereas the average photographer shows everything. Perhaps in the art world, it is better to be exclusive and strive for perfection, but in the world of idea generation, which is really what investing is about at its core, I think it’s more productive to put more volume out there than less.”

The real-world AI that could change everything

This week, we published a deep-dive research report into what’s happening on the bleeding edge of real-world artificial intelligence — and autonomous robotics.

Our takeaway: the first wave of AI-based products will be in desktop-based applications (i.e. ChatGPT, Gemini, etc.). But the next wave, which could potentially be even more profound, will be in real-world hardware applications: self-driving cars, humanoid robotics, and so on. Far from a distant reality, our conclusion is that these technologies are much closer than many people appreciate.

“It is a change in computing paradigms that could rival the introduction of the railroad, aviation, automobiles, and the Internet,” we write. “These revolutionary innovations didn’t just disrupt industries; they redefined global economies, unlocked unprecedented efficiencies (and profits), and transformed the way we live.”

Key quote: “In the past 12 months, our research leads us to believe — with a high degree of confidence — that self-driving cars have reached a major turning point. It’s no longer just another R&D line-item on an income statement. It’s real. For long-term investors looking to capitalize on artificial intelligence, the biggest opportunity lies in autonomy: self-driving vehicles (and humanoid robots) could transform industries like transportation, logistics, healthcare, real estate, and insurance.”

The long-term advantages of “radical optimism”

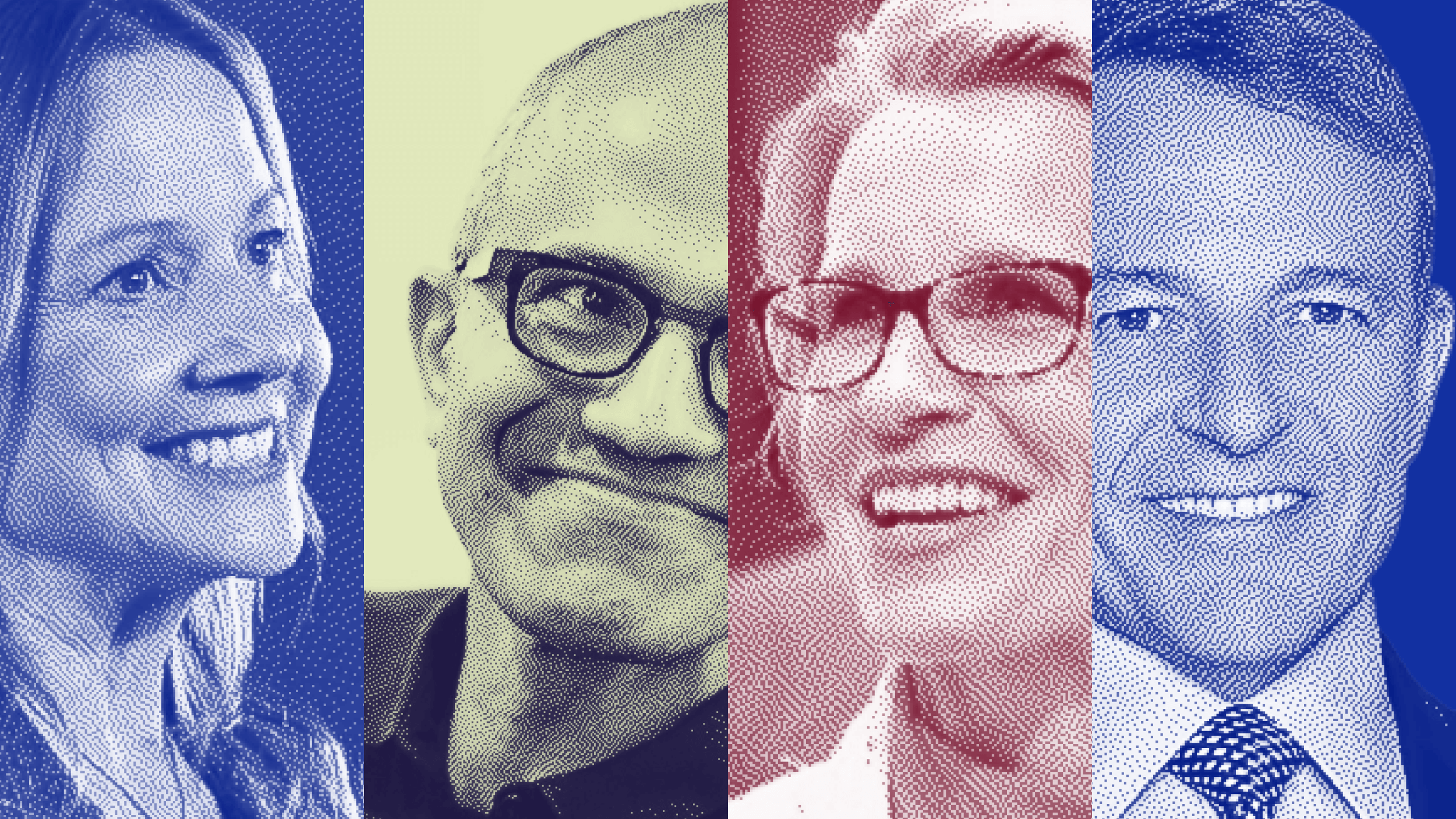

For my latest column in The Long Game, I spoke with someone who has been profoundly influential in how I think about long-termism: Kevin Kelly.

Kevin is an author, philosopher, technologist, entrepreneur, artist, and the co-founder of WIRED magazine. He’s also just a genuinely kind person with a very clear message: in order to think — and act — for the long-term, we need to remain unabashedly optimistic in an increasingly pessimistic world. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Key quote: “The longer your view is, the more optimistic you can become. A longer view allows you to overcome the inevitable setbacks that will be present in the short term. If you look at a chart of the stock market over time, World War II — which was a big, terrible setback — hardly shows up. The point is you can overcome it. The power of a few percent compounded over time is so great that it can offset very severe setbacks in the short term. Miracles can happen if you give yourself 10 years to accomplish something rather than three months or six months.”

A few more links I enjoyed:

Nick Sleep’s Letters: The Full Collection of the Nomad Investment Partnership Letters to Partners – via Founders

Key quote: “Nick Sleep’s letters are a masterclass on the importance of understanding the underlying reality of a business — what he calls the engine of its success. I read all 110,000 words of Nick’s letters (twice!) to make this episode and what I found most important is Nick’s ability to develop a deep understanding of ‘honestly run compounding machines’ (like Costco and Amazon) years before everyone else. Nick explains clearly how Jim Sinegal and Jeff Bezos set up their companies for long term success — from the very beginning — and gives us a few hints along the way on how we can do the same in our business. And the absolute entrepreneurial history nerd in me loved the references to Henry Ford, Sam Walton, Rockefeller and other greats from the past that are sprinkled throughout Nick’s letters. No surprise that someone who was able to make $2 billion for his clients has a deep understanding of the great work that came before him.”

What Comes After SB 1047? – via Dean Ball

Key quote: “Imagine if you had to file paperwork with the government every time you wanted to use a computer to do something novel. Imagine if you had to tell the government how your computer has no adverse impact on ‘decisions that materially impact access to, or approval for, housing or accommodations, education, employment, credit, health care, and criminal justice’ — every time you wanted to do something novel with a computer, and regardless of whether your computer use had anything to do with those things.”

Just do it! Brand Name Lessons from Nike’s Troubles – via Aswath Damodaran

Key quote: “Put simply, brand name value can show up in almost every input, with a more recognizable (and respected) brand name leading to more sales (higher revenues and revenue growth), more pricing power (higher margins), and perhaps even less reinvestment and less risk (lower costs of capital and failure risk). That said, the strongest impact of brand name is on pricing power, with brand name in its purest form allowing it’s owner to charge a higher price for a product or service than a competitor could charge for an identical offering.”

Visualizing the Power of Limitation – via Coleman McCormick

Key quote: “In short, the most creative solutions or discoveries emerge in the presence of constraint — on time, money, attention, resources, environment. Creating in constrained space unlocks something mentally for us that we can’t easily access when we’ve got green fields, infinite budgets, or no calendar deadlines.”

From the archives:

Technical Revolutions – via Carlotta Perez (2004)

Key quote: “This paper puts forth a particular interpretation of the long wave phenomenon, which offers to provide criteria for guiding social creativity in times such as the present. Basically, the present period is defined as one of transition between two distinct technological styles — or techno-economic paradigms — and at the same time as the period of construction of a new mode of growth. Such construction would imply a process of deep, though gradual, change in ideas, behaviors, organizations and institutions, strongly related to the nature of the wave of technical change involved.”