“Life does not exist”: The deceptively tricky task of defining life

- In the 2024 book Life As No One Knows It, physicist and astrobiologist Sara Imari Walker explores the thorny problem of defining life.

- Walker explains why our current definitions of life fall short, arguing for a new and experimentally testable theory for what life is.

- In this excerpt from her book, Walker overviews how the boundaries between life and nonlife began to blur as humans began to learn more about chemistry and its underlying physics.

Have you ever wondered what makes you alive? What makes anything alive?

At the 2012 meeting of the American Chemical Society, in a session on the origin of life, Andrew Ellington proposed a radical theory: “Life does not exist.” Andy is a chemistry professor from the University of Texas at Austin, and this was the first slide of his presentation on RNA chemistry and the origin of life. His idea left me incredibly perplexed.

I was perplexed because I probably should have agreed with Andy. But I don’t. When I attended Andy’s lecture I was pretty sure I was alive, as I am now. You’re probably confident you are alive too. Haven’t you spent your whole life, well, living? Being alive matters. It’s very different from not being alive.

Yet despite our natural confidence in our own existence, some scientists challenge it and argue that life may be just an illusion or epiphenomenon, explainable by known physics and chemistry.

Physicist and public intellectual Sean Carroll is one such individual. In a crowded evening lecture on the Arizona State University campus where I work, I was aghast in my seat as Sean stated how the equations of particle physics are sufficient to explain the existence of all matter—including you and me. Jack Szostak, a Nobel Prize winner, holds a similar view, arguing that the focus on defining life is holding us back from understanding life’s origin. According to Jack, the closer you look at any of the “defining” properties of life, the more the boundary between life and nonlife blurs.

As a child, I remember trying to take an insect apart and then failing to restore it to its original state. I was too surprised at the time to even feel upset. We are all familiar with how life cannot be reduced to its parts, be they elementary particles, atoms, or even molecules. Perhaps it is easiest to take the view, as Andy, Jack, and Sean do, that life is not a property of its parts, and that therefore we don’t need to worry about defining it. If true, it follows that all we need to understand what life does and how it emerges is to understand those parts.

In my training as a theoretical physicist, I was taught to believe that life was not a conceptually deep scientific problem. Instead, the most fundamental concepts regarding the nature of reality were what other physicists had studied—things like space, time, light, energy, and matter. Indeed, the successes of physics have been nothing short of profound: over the short span of the last four hundred years, we have gained a deep understanding of how our universe works. We have even defined what we mean by “universe.” At the very small scales, we understand much about the elementary constituents of all matter. At the very largest scales, we can take photos of distant galaxies whose light took more than 13.5 billion years to reach our telescopes.

Yet the origin of life remains one of the greatest puzzles in science. Physics, as we collectively understand it at this moment in history, provides a fundamental description of a universe devoid of life. It’s not the universe I live in, and I bet you don’t live there either.

But if life does exist, what is it?

What are we?

If Vitalism Is Dead, Maybe You Are Too

In stark contrast to the views of modern physicists and chemists, scientists used to believe life exists as a separate category from matter.

Animated matter was believed to be imbued with a “vital” force, sometimes referred to as the élan vital. Aristotle called it entelechy; Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz called it monads. They were both describing, as many have, a unique quality found only in living entities that directs living behaviors, such as the development of an embryo, regeneration of a lost limb, or any of the other purposeful activities that seem uniquely characteristic of life. This concept of being alive is somewhat akin to the religious concept of a soul, and some have even called it that. Whatever you call it, we think these features are unique to life because we do not observe them in nonliving things. A rock does not restore its original shape when cut in two, but a planarian worm can and does. Vitalism, as the scientific movement came to be called, was driven by the idea that what makes matter come alive cannot be described mechanically and is therefore not material.

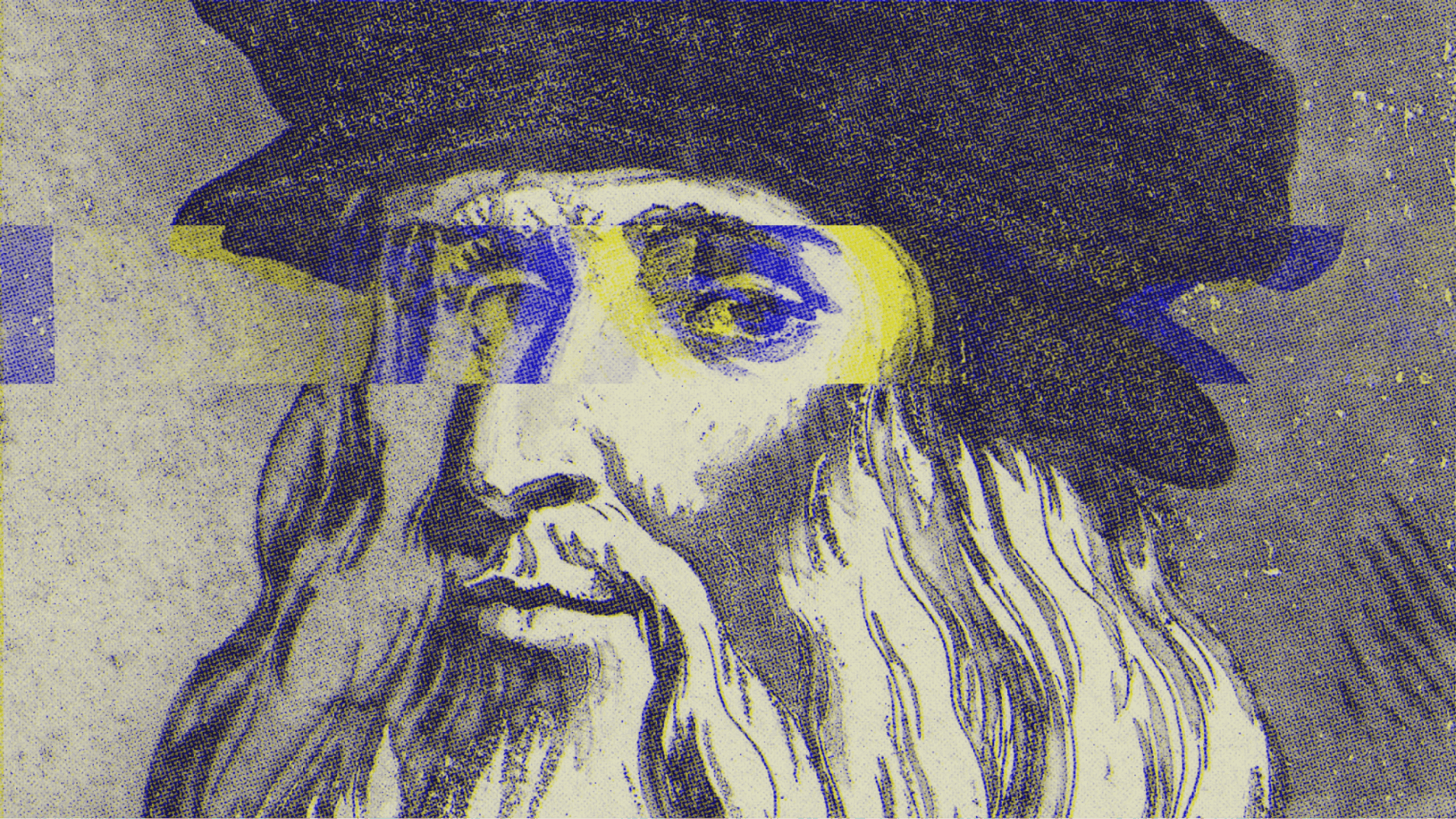

While modern materialists like Andy, Sean, and Jack regard the known properties of matter as sufficient for explaining life, the vitalists had quite the opposite view. They believed that life does, in fact, exist, but it cannot be explained in terms of the properties of matter. Often, the idea of a vital principle was discussed in terms of a life energy or vital spark that could animate even dead matter. If this sounds a bit Frankensteinian, that’s because it is. Mary Shelley was just twenty-one when her famous novel Frankenstein was published in 1818. When she penned the book, she was reflecting on the leading science of her day, particularly theories on the soul, what makes us alive, and how we might reanimate the dead with electricity. Mary was influenced by the contemporary work of Luigi Galvani, work later carried on by his nephew Giovanni Aldini. These two attempted to animate body parts through electrostimulation; they would stimulate dead frogs’ legs with electric shocks to make them “dance.” Mary was also reportedly inspired by Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of the more famous Darwin, Charles. The elder Darwin wrote on the topic of spontaneous generation, citing how inanimate materials could spontaneously become animated in water warmed by sunlight.

In Mary’s novel, the body parts of the recently deceased could be reanimated by electrocution if they were properly wired together. This is how her lead character, Dr. Victor Frankenstein, made his “living” monster from dead bodies. If we were to try to write down laws of physics that could explain Dr. Frankenstein’s unique insight in animating the monster, we might conjecture he had discovered a life “force” that dissipated slowly after death, and that whatever substance this force was made of was strongly coupled to electromagnetism. It’s a bit of an odd set of properties Dr. Frankenstein discovered in his fictional universe, but matter in our real universe has many strange properties too. Our universe is weird when you start to understand it (in fact, it gets odder the more you think you understand it).

We might imagine a consistent physics that Dr. Frankenstein tapped into that explains life. It just so happens that whatever physics he was onto is not the physics that describes our real universe. The real physics underlying life might be even stranger still. While right now we do not understand what principles govern life, they may one day be as obvious to subsequent generations as the curvature of space-time or the existence of particles of light (photons) are to us now.

Many of the vitalists thought life could not be produced by things that were not already themselves alive. Living matter was special because its parts were special, carrying some of that requisite élan vital. Thus, living things were necessary to make more living things; even Dr. Frankenstein had to make his monster from once living parts that were only recently deceased.

Around the time of the publication of Frankenstein, the idea that life is necessary to produce the stuff of life was already beginning to lose popular support within the scientific community. In 1828, Friedrich Wöhler synthesized urea, an organic molecule found in urine, from two other simple molecules, cyanic acid and ammonium. Friedrich’s experiment showed that biologically derived molecules do not carry any sort of life force. The component parts of living matter are no different from those of nonliving matter. In experiments like these, scientists have repeatedly demonstrated that there is nothing that separates the properties of nonliving chemistry from living chemistry: the former can easily be transformed to the latter under appropriate conditions. The sharp boundary between nonlife and life started to blur as humanity began to understand more about chemistry and the physics underlying it. Sean, Jack, Andy, and many others who hold similar views are right . . . to a degree.

In fact, as much as we have looked, we have found the transformation from a nonliving to a living substance is not excluded by any known law of physics or chemistry. There is no life conservation law that says life cannot be created or destroyed. Of course, this is obvious, because we know organisms are born and die— but sometimes it is the most obvious observations that are the hardest to explain scientifically, and harder still to turn into mathematical law.

What modern science has taught us is that life is not a property of matter.

Physicists and chemists see very intimately what the rest of us who think life exists cannot: there is no magic transition point where a molecule or collection of molecules is suddenly “living.”

Life is the vaporware of chemistry: a property so obvious in our day-to-day experience—that we are living—is nonexistent when you look at our parts.

If life is not a property of matter, and material things are what exist, then life does not exist. This is probably the logic Andy was going for.

Yet here we are.