Workplace “aporia”: How to handle unresolvable arguments

- Sometimes, you will witness or be part of a debate where there is no resolution. Both parties will reach an uncrossable divide.

- This point is known as “aporia” in ancient Greek.

- We look at three manifestations of aporia and consider how we can resolve them.

It’s late in the night, and Mollie and Seb have been having the same argument for an hour now. Everyone else has gone quiet. They occasionally throw in a line or two, but they mostly just want to go to bed. The argument has long since gone around in circles. It’s going nowhere. It’s not a shouting match by any means. Mollie and Seb are both reasonable, respectful, and calm. It’s just that they’ve reached “That Point.”

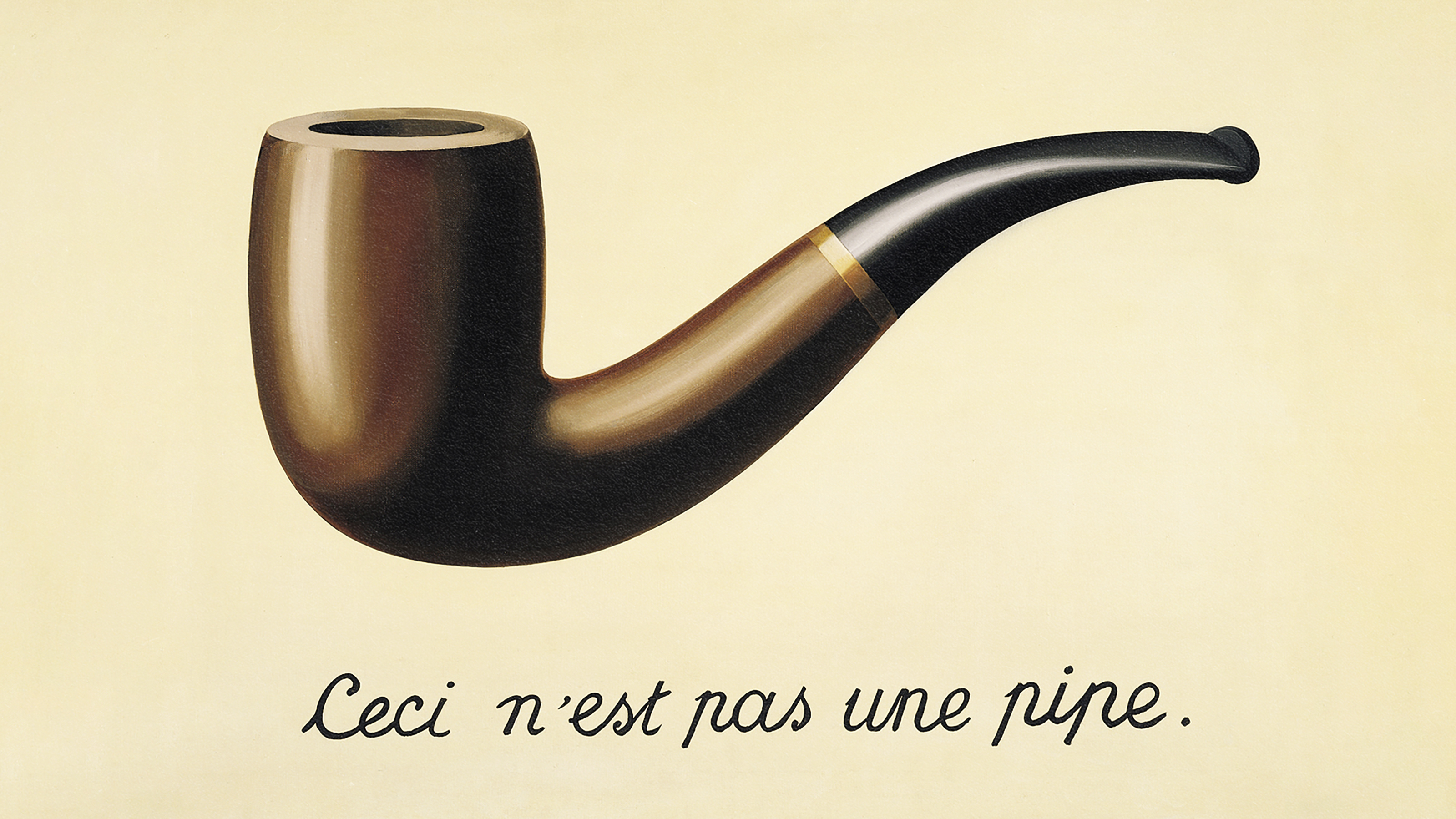

That Point is the part of a debate where rational argument can go no further. They’ve each unpacked one another’s premises and called out non-sequiturs, ad hominem arguments, and false dichotomies aplenty. But That Point cannot be crossed. It’s a locked door and an unbudgeable rock. That Point is the moment you say, “Well, that’s just what I believe.”

Consider the following argument, examined in Alasdair MacIntrye’s After Virtue:

“Justice demands that every citizen should enjoy, so far as is possible, an equal opportunity to develop his or her talents and his or her other potentialities. But prerequisites for the provision of such equal opportunity include the provision of equal access to health care and to education.”

It’s a rational, convincing, and plausible ethical position. Yet nothing can budge. The debate depends almost entirely on the weight you ascribe to “justice.” That Point is known as aporia in philosophy. There are moments when there is a problem or a conflict with no possible (or, at least, no apparent) resolution. An unsolvable puzzle. A riddle with no answer.

We look at how common aporia is and how we can deal with it in the workplace.

Let’s agree to disagree

In our opening example, let’s imagine Seb is trying to persuade Mollie that battery farms are immoral. They debate and argue, and Seb says, “Don’t you care about animal suffering?” and Mollie honestly replies, “Well, no, not really.” Where does Seb go from here? What more can Seb say?

In our everyday social interactions, there will come a point when you meet someone who holds drastically and fundamentally different views from you about a topic. Their starting position and their initial premises are different. This is aporia. When this occurs, what usually happens is one of two things. Either you resort to name-calling,: “You monster!” Or, you agree to disagree and hope to go about your lives as smoothly as possible.

The defining characteristic of aporia is that there is no workable compromise position. Let’s say, at work, that someone prefers meetings in the morning and someone else prefers them in the late afternoon. A compromise position might be to arrange meetings around 11 a.m. or even to mix it up. No one’s entirely happy, but the meeting gets done, and the conflict has been resolved. Aporia, though, allows no middle ground. Two rams will butt heads until one is either broken or has fled.

Resolving the unresolvable

What happens, then, if aporia pops up in your workplace? How do you deal with unresolvable dilemmas and uncompromisable positions in your interactions with colleagues? Here we look at three examples and possible solutions.

Get rid of the personality. There are few things so popular in the corporate world as a good, increasingly old-fashioned psychometric test. Even if your company hasn’t officially conducted one, you can bet many people think in terms of them. “Oh, she’s such a Type A person,” someone might say. Even if you’re suspicious of psychometric tests, the fact is that you will find some people at work hard to work with. You’ll find conversations hard, and the workflow is more work-trickle. How, then, are you to reconcile the fundamental difference in personality? One study from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, offers up two practical pieces of advice. First, “start the discussion by describing the gap between the expected and observed behavior.” Be honest about how you see yourself and how you see other people. Second, “[begin] with the facts from your perspective… and share all appropriate and relevant information.” Keep it as neutral, objective, and professional as you can. In other words, if there’s a clash of personalities, try to get rid of the personality.

Use cutting-edge translation tools. There is nothing so unresolvable as literally not understanding someone. It’s rare for a company to have people of entirely different languages, but it’s increasingly common for a colleague’s language to be a second language. Struggling to communicate with someone can be both demoralizing and inefficient. Time is lost explaining terms and ideas. The instructions or requirements might be confusing. There are two ways to resolve this. The old-school way is to invest in translation services or use more visual aids. Reduce the use of overly complex language, where possible. The second way is more modern. This year will be the year of AI translation. There are already a great many options for “live translations,” and it’s a safe bet these will be common and freely included in existing services by the end of the year.

Build in a response buffer. It’s likely that you will, eventually, have some kind of conflict with someone at work. Often, that will be about some moveable and time-sensitive issue. At other times, it’s aporia. It’s irreconcilable. In these instances, it can be quite easy to simply label that someone as “that conflict person.” You will go into meetings with them tense. You’ll be looking for slights and annoying habits. You want them to fail, and you’re ready to pounce on the smallest mistake. On Big Think+, Dan Shapiro, Director of the Harvard International Negotiation Program and author of Negotiating the Nonnegotiable, calls this “repetition compulsion.” It’s a Freudian idea that you will behave with someone out of habit, not rationally. In the video, Shapiro gives a great many ways to combat the issue, for example, by just taking ten minutes to think before you respond to someone you find hard.