5 books you probably haven’t read (and how to pretend you have)

- When it comes to literature, you sometimes have to discuss books you’ve never read and bluff your way through the conversation.

- There are some general tips for managing this successfully, such as feigning memory loss and learning the basic ideas behind the books.

- Here is some advice on bluffing your way through five much lauded, but seldom read, books.

For one reason or another, you sometimes have to talk about a book you haven’t read. It might be that you want to impress your boss or appear intellectual on a first date. It might be that you’ve got a selection of books on your shelves that one looks suspiciously new, with its pristine spine and unthumbed pages. So, what do you do if someone asks you about those books? How do you respond if someone presses you for more than a blurb’s worth of information?

To help you on your way to Blagville, we’ve compiled five of the most common books people pretend to read and explain how to bluff your way through a conversation about them.

War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy

Bluffer’s blurb

It’s a snowy, cold evening in St. Petersburg in 1805. The rich and mighty of Russian society are hobnobbing and chortling away with caviar and clinking glasses of bubbly. Bursting in on the scene is Napoleon with his undefeated French army. Russian high society reels. It’s time to go to war. No more fireplace flirting and ballroom dances. Now is the time for patriotism, comradeship, and frozen battlegrounds steaming with spilled blood.

What should I say?

War and Peace is nearly 600,000 words long. No one can remember the whole thing. The best bet is to feign memory loss or at least memory fragmentation: “Oh, I read it a while ago, but I can remember only a few things.”

What are those few things? First, there is the jarring dissonance between the comfortable domesticity of Mother Russia and the brutality of war. Second, the transformations of Prince Andrei and Natasha. Prince Andrei hates his aristocratic life and initially welcomes the war and the opportunity for glory. After a near-death experience, he looks for love and deeper meaning. Natasha is a carefree and naïve socialite. But various heartbreaks and the ongoing war turn her from an impulsive girl into a resilient and mature woman. “The personal narratives of the characters essentially mirror the geopolitical ones” is a great line to drop.

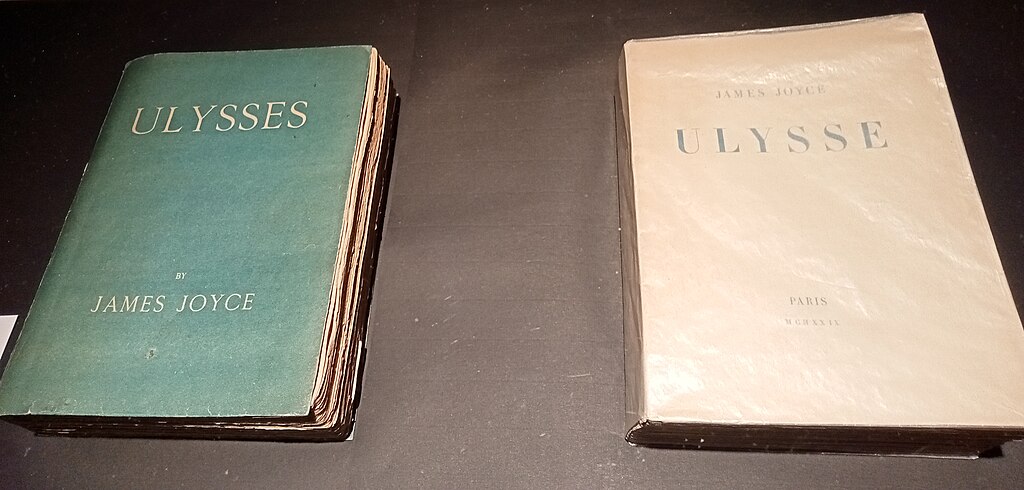

Ulysses, by James Joyce

Bluffer’s blurb

Imagine the closest thing you can to someone’s stream of consciousness written on a page. But this is not a curated, edited, and formatted diary entry, but a messy, confusing, random slideshow of thoughts. This is Ulysses. It’s a human mind’s experience in the streets of Dublin on an ordinary day in 1904.

What should I say?

Ulysses is the literary gemstone for any English literature graduate, an experiment in language as much as plot. When blagging, you will want to hug closely to the deliberately enigmatic aspects of the novel: “I never felt I could entirely grasp what was going on. It was like letting the story flow over me.” Mention how each chapter has a different tone and style, and how that reflects human life well. Humans change all the time, and so a stream of consciousness will change too.

The book also has an epic, mythological feel to it. There are many allusions to the Odyssey, for instance, so you could mention how it felt mysterious and yet strangely familiar.

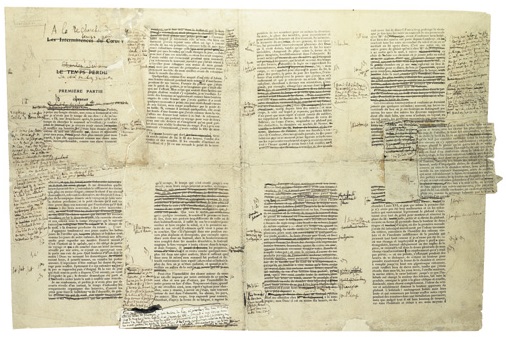

In Search of Lost Time, by Marcel Proust

Bluffer’s blurb

In many ways, Proust is similar to Joyce — which is a nice blagging line itself. His multi-volume novel is written in a stream of consciousness as well; however, this stream meanders into the hidden geography of Proust’s memory. There is a plot of sorts, but it’s more of a Tarantino time-warp of overlapping plots that (kind of) converge into a whole.

What should I say?

Proust is like an invitation to remember aspects of your own life. The defining feature of In Search of Lost Time is “involuntary memories.” These are memories that hit you like an unexpected steam train when you’re busy doing something else. A wiff of a passerby’s perfume conjures up an image of your dead grandmother. A song reminds you of that summer when you got your exam results. Proust’s autobiographical, gate-crashing memories elicit your own.

Say something like, “Funnily enough, whenever I read Proust’s recollections, I have my own. The way he talks about those madeleines made me consider how important food is to memory.”

Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville

Bluffer’s blurb

Moby Dick is about obsession. It’s about that pathologically addictive and irrepressibly driven aspect we all have for something. Ahab lost his leg to the white whale — which is fair grounds for revenge in his book — and the novel chronicles the dark, neurotic extremes he undergoes to hunt the limb-munching cetacean.

What should I say?

Try and defend a “hot take” with this one. Mention something like, “Most people focus on the obsessive aspect of hunting for something that gets away, the white whale that can never be caught. But I think it’s more about how contagious obsession is.”

In Moby-Dick, Ahab is not only obsessed; he needs everyone else to share in his obsession. In one evocative scene, Ahab cajoles, bribes, and threatens his crew to take up his mania. Like anyone who’s truly, fanatically, madly obsessed, he needs everyone to feel the same way. Make this about the dark side of neurosis — not only on the sufferer but on those who are damaged in their wake.

Paradise Lost, by John Milton

Bluffer’s blurb

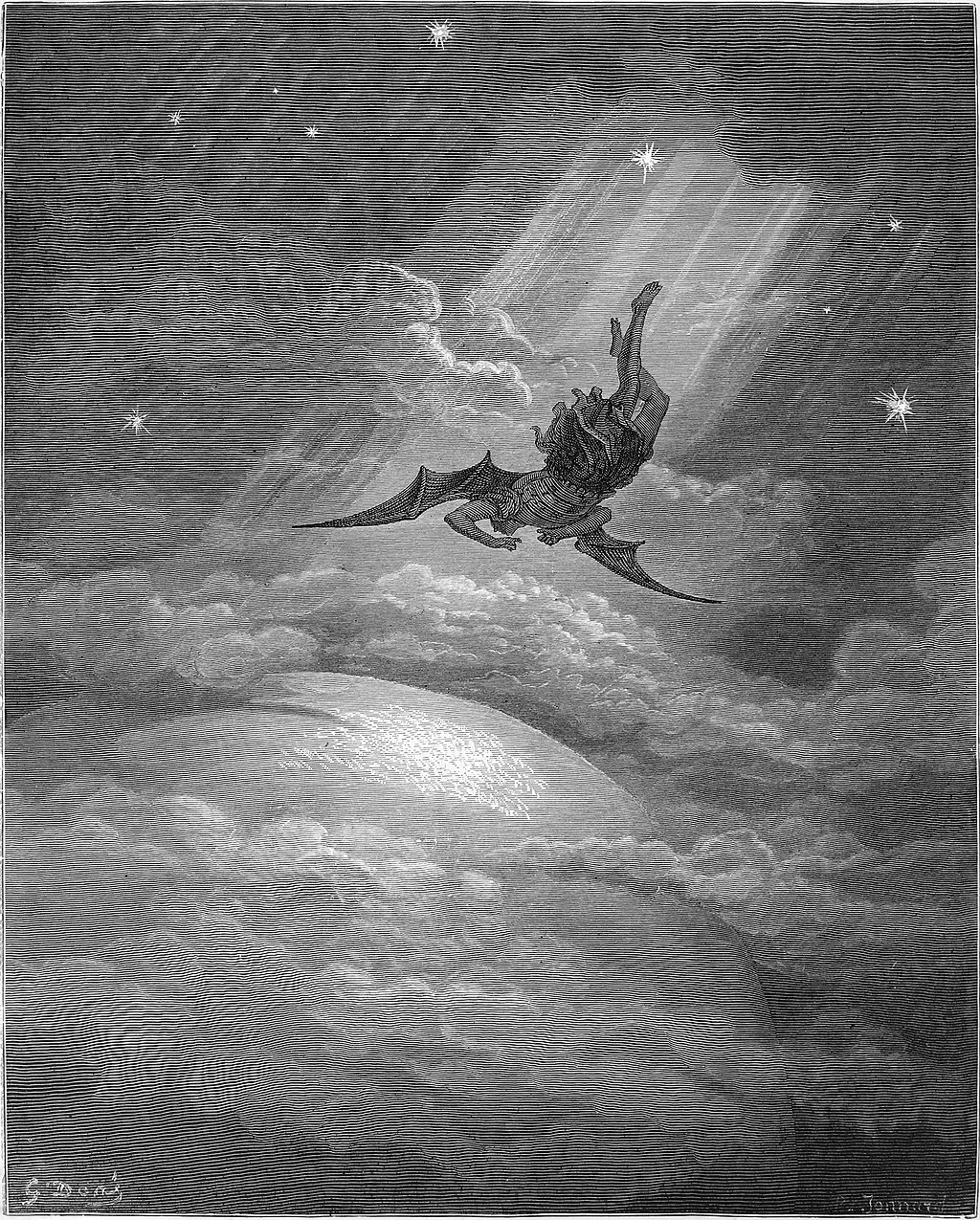

Paradise Lost is Milton’s version of a Christian epic saga. Ostensibly, it’s a 17th-century epic poem about angels and demons — a Hollywood screenwriter’s dream of celestial battles pitting heavenly forces against the depths of hell. But it’s really about the human struggle between good and evil.

What should I say?

Rather than feign memory loss, feign confusion. Paradise Lost is so popular and so enduring that its influence can’t be overstated. Say something like, “I’m not sure anymore what is actually Paradise Lost and what I’ve seen in paintings or popular culture since.” It’s in Frankenstein; it’s in His Dark Materials. Any movie or TV plot featuring warring angels and demons is basically Milton with special effects.

Of course, if you want to blag, you can’t rest on “Well, I saw the movie.” Mention two things: First, how Milton uses metaphor and poetry so artfully to evoke incredible feelings and imagery. Second, talk about how subtle and complex Satan is. He is not diabolical. He is not totally lost. He is a fallen angel with legitimate grievances.

Oh, and be sure to mention how William Blake even reinterpreted Satan as “the hero.” You can even toss in the famous footnote from Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “[Milton] was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” Now that’s some next level blagging.