Creative people’s brains are uniquely wired, scientists discover

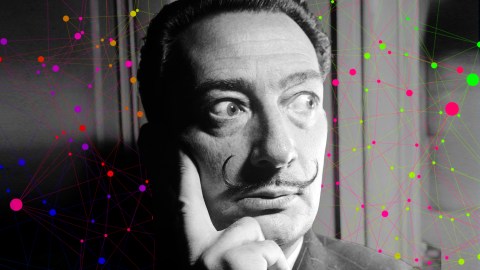

One of the most important aspects of innovation is creativity. But the trait has been elusive. How on earth do you generate it? Stories of artists regale us with bizarre methods. For instance, Salvador Dali would nap in a chair with his keys dangling over a metal plate. Once he relaxed enough to let go of the keys, they’d go crashing down onto the plate, rousing him from his slumber, his dream still fresh in his mind. Dali would then rush to capture the memory of his dream.

Russian-American composer Igor Stravinsky had an altogether different but no less bizarre method. He would stand on his head, in a way taught to him by a Hungarian gymnast. The act, he claimed, would “clear his brain.” While inventor Yoshiro Nakamatsu who had 3,000 patents to his name—including the floppy disc—would go on dives and wait beneath the waves for inspiration to come, which he said often arrived “just 0.5 seconds before death.”

We don’t get progress on technology or the arts without creativity. And yet, artists and inventors have had such varying and oftentimes outlandish methods that neuroscientists have wondered whether or not there are certain uniform patterns associated with the creative state. Due to its centrality, such scientists have argued whether they can decipher creativity, or boost it in a methodical way. This latest study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), suggests we can.

Artists use varying and sometimes bizarre methods to inspire creativity. Credit: Getty Images.

What researchers discovered is that when we’re being creative, a certain neurological pattern or signature occurs inside the brain. “We identified a brain network associated with creative ability comprised of regions within default, salience, and executive systems—neural circuits that often work in opposition,” researchers write. “Across four independent datasets, we show that a person’s capacity to generate original ideas can be reliably predicted from the strength of functional connectivity within this network, indicating that creative thinking ability is characterized by a distinct brain connectivity profile.”

Don’t worry. We haven’t yet developed some Phildickian mind-reading machine. Instead, researchers are just beginning to understand what neurological patterns are associated with creativity. Psychologist Roger Beaty of Harvard University told The Guardian, “We have identified a pattern of brain connectivity that varies across people, but is associated with the ability to come up with creative ideas.” He added, “It’s not like we can predict with perfect accuracy who’s going to be the next Einstein, but we can get a pretty good sense of how flexible a given person’s thinking is.”

The networks involved are the default mode network, the executive control network, and the salience network. The default mode network is what takes over when you daydream or your mind wanders off. If you ever started your commute and ended up at home, without any memory of driving there, you’ve had your default mode network engaged. The executive control network kicks in when you are fully engaged with your thoughts, making plans, decisions, learning, remembering, and so on. And the salience network is what helps us decide what to pay attention to, and what to ignore. Among the three brain networks, two work against one another. What creative people can do better than others is the ability to apprehend insights coming from each system simultaneously. “An interesting feature of these three networks is that they typically don’t get activated at the same time,” Beaty writes. “For example, when the executive network is activated, the default network is usually deactivated. Our results suggest that creative people are better able to co-activate brain networks that usually work separately.”

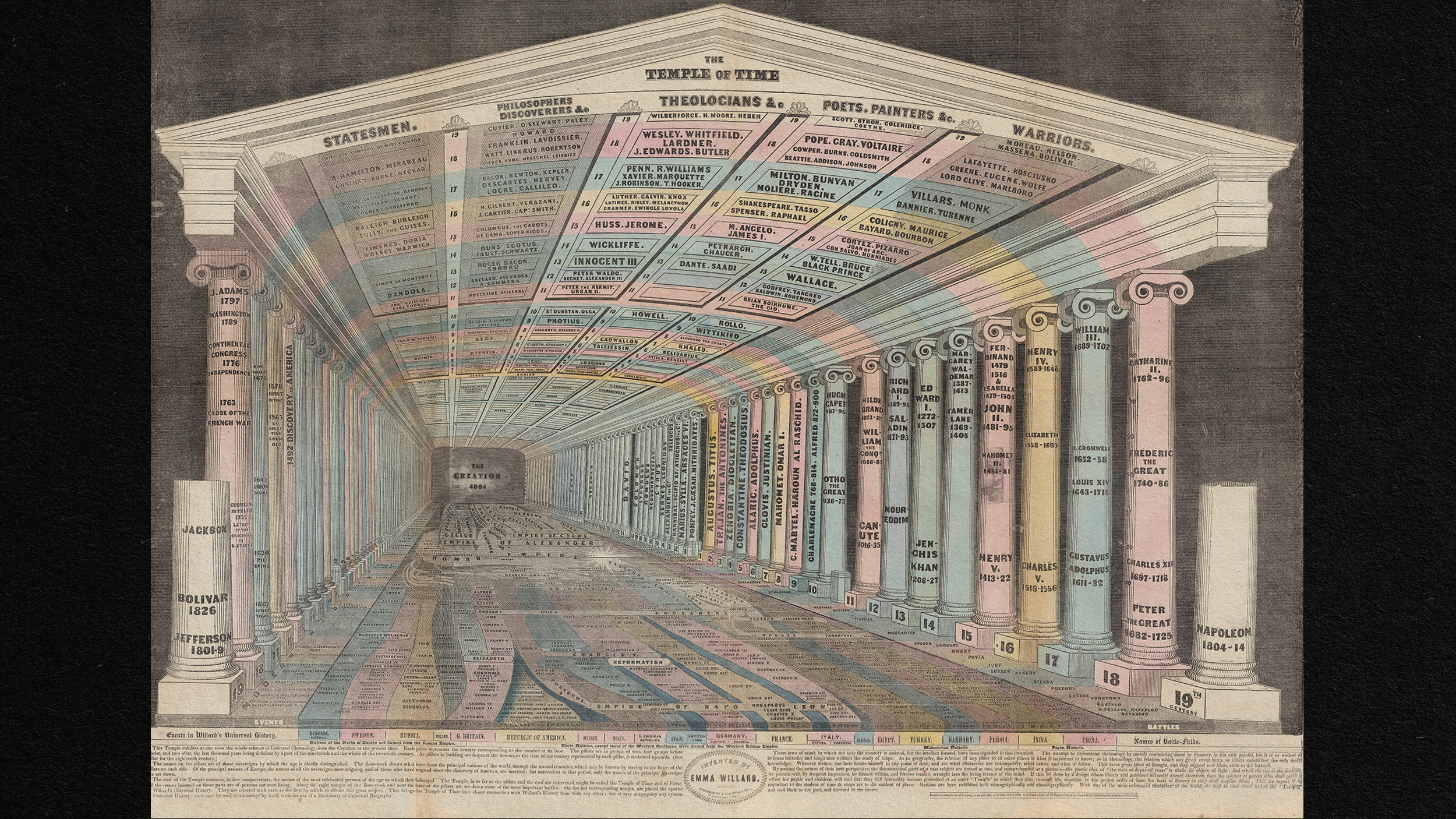

Credit: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In this study, Beaty and Austrian and Chinese colleagues recruited 163 participants. Creative types such as musicians, artists, and scientists were recruited. Each took part in what was called “a classic divergent thinking task,” while hooked up to an fMRI. Recruits had 12 seconds to think up the most creative use for mundane objects such as a sock, a bar of soap, or a gum wrapper. The recruits called out their answer as quickly as they could when it flashed upon a screen. Participants’ white matter was scanned as they answered. As for the level of creativity, recruits’ answers were scored by independent assessors.

Previous research at the University of North Carolina concluded with the same results. In future studies, researchers want to scan the brains of people taking part in the arts, sciences, and other creative pursuits, to see if they identify ways to boost the creative juices. In the U.S., arts programs have suffered deep budget cuts in schools across the nation. Has this harmed the development of future innovators? Researchers must find out in future studies if creativity is translatable or inherent to each individual.

To learn more about the intersection of neuroscience and creativity, click here: