Can we understand other minds? Novels and stories say: no

Cassandra woke up to the rays of the sun streaming through the slats on her blinds, cascading over her naked chest. She stretched, her breasts lifting with her arms as she greeted the sun. She rolled out of bed and put on a shirt, her nipples prominently showing through the thin fabric. She breasted boobily to the stairs, and titted downwards.

This particular hyperbolic gem has been doing the rounds on Tumblr for a while. It resurfaced in April 2018, in response to a viral Twitter challenge posed by the US podcaster Whitney Reynolds: women, describe yourself the way a male writer would.

The dare hit a sweet spot. Many could summon up passages from books containing terrible, sexualised descriptions of women. Some of us recalled Haruki Murakami, whose every novel can be summarised as: ‘Protagonist is an ordinary man, except lots of really beautiful women want to sleep with him.’ Others remembered J M Coetzee, and his variations on the plot: ‘Tenured male professor in English literature sleeps with beautiful female undergraduate.’ It was a way for us to joke about the fact that so much great literature was written by men who could express perfectly detailed visual descriptions of the female body, and yet possessed such an impoverished understanding of the female mind.

This is why the philosophical project of trying to map the contours of other minds needs a reality check. If other humans are beyond our comprehension, what hope is there for understanding the experience of animals, artificial intelligence or aliens?

I am a literature scholar. Over thousands of years of literary history, authors have tried and failed to convey an understanding of Others (with a capital ‘O’). Writing fiction is an exercise that stretches an author’s imagination to its limits. And fiction shows us, again and again, that our capacity to imagine other minds is extremely limited.

It took feminism and postcolonialism to point out that writers were systematically misrepresenting characters who weren’t like them. Male authors, it seems, still struggle to present convincing female characters a lot of the time. The same problem surfaces again when writers try to introduce a figure with a different ethnicity to their own, and fail spectacularly.

I mean, ‘coffee-coloured skin’? Do I really need to find out how much milk you take in the morning to know the ethnicity you have in mind? Writers who keep banging on with food metaphors to describe darker pigmentation show that they don’t appreciate what it’s like to inhabit such skin, nor to have such metaphors applied to it.

Conversely, we recently learnt that some publishers rejected the Korean-American author Leonard Chang’s novel The Lockpicker (2017) – for failing to cater to white readers’ lack of understanding of Korean-Americans. Chang gave ‘none of the details that separate Koreans and Korean-Americans from the rest of us’, one publisher’s letter said. ‘For example, in the scene when she looks into the mirror, you don’t show how she sees her slanted eyes …’ Any failure to understand a nonwhite character, it seems, was the fault of the nonwhite author.

Fiction shows us that nonhuman minds are equally beyond our grasp. Science fiction provides a massive range of the most fanciful depictions of interstellar space travel and communication – but anthropomorphism is rife. Extraterrestrial intelligent life is imagined as Little Green Men (or Little Yellow or Red Men when the author wants to make a particularly crude point about 20th-century geopolitics). Thus alien minds have been subject to the same projections and assumptions that authors have applied to human characters, when they fundamentally differ from the authors themselves.

For instance, let’s look at a meeting of human minds and alien minds. The Chinese science fiction author Liu Cixin is best known for his trilogy starting with The Three-Body Problem (2008). It appeared in English in 2014 and, in that edition, each book has footnotes – because there are some concepts that are simply not translatable from Chinese into English, and English readers need these footnotes to understand what motivates the characters. But there are also aliens in this trilogy. From a different solar system. Yet their motivations don’t need footnoting in translation.

Splendid as the trilogy is, I find that very curious. There is a linguistic-cultural barrier that prevents an understanding of the novel itself, on this planet. Imagine how many footnotes we’d need to really grapple with the motivations of extraterrestrial minds.

Our imaginings of artificial intelligence are similarly dominated by anthropomorphic fantasies. The most common depiction of AI conflates it with robots. AIs are metal men. And it doesn’t matter whether the press is reporting on swarm robots invented in Bristol or a report produced by the House of Lords: the press shall plaster their coverage with Terminator imagery. Unless the men imagining these intelligent robots want to have sex with them, in which case they’re metal women with boobily breasting metal cleavage – a trend spanning the filmic arts from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) to the contemporary TV series Westworld (2016-). The way that we imagine nonhumans in fiction reflects how little we, as humans, really get each other.

All this supports the idea that embodiment is central to the way we understand one another. The ridiculous situations in which authors miss the mark stem from the difference between the author’s own body and that of the character. It’s hard to imagine what it’s like to be someone else if we can’t feel it. So, much as I enjoyed seeing a woman in high heels outrun a T-Rex in Jurassic World (2015), I knew that the person who came up with that scene clearly has no conception of what it’s like to inhabit a female body, be it human or Tyrannosaurus.

Because stories can teach compassion and empathy, some people argue that we should let AIs read fiction in order to help them understand humans. But I disagree with the idea that compassion and empathy are based on a deep insight into other minds. Sure, some fiction attempts to get us to understand one another. But we don’t need any more than a glimpse of what it’s like to be someone else in order to empathise with them – and, hopefully, to not want to kill and destroy them.

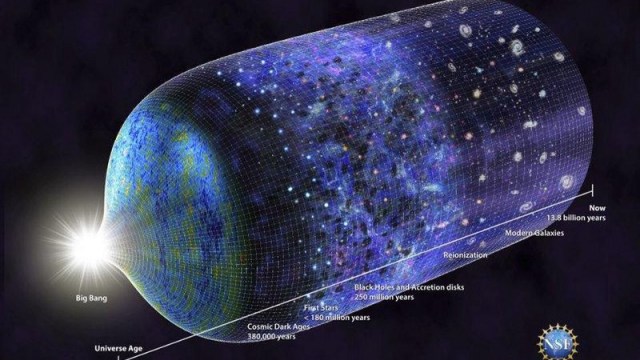

As the US philosopher Thomas Nagel claimed in 1974, a human can’t know what it is like to be a bat, because they are fundamentally alien creatures: their sensory apparatus and their movements are utterly different from ours. But we can imagine ‘segments’, as Nagel wrote. This means that, despite our lack of understanding of bat minds, we can find ways to keep a bat from harm, or even nurse and raise an orphaned baby bat, as cute videos on the internet will show you.

The problem is that sometimes we don’t realise this segment of just a glimpse of something bigger. We don’t realise until a woman, a person of colour, or a dinosaur finds a way to point out the limits of our imagination, and the limits of our understanding. As long as other human minds are beyond our understanding, nonhuman ones certainly are, too.

Kanta Dihal

This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.