How schizophrenia is linked to common personality type

(shutterstock)

- A new study shows that people with a common personality type share brain activity with patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.

- The study gives insight into how the brain activity associated with mental illnesses relates to brain activity in healthy individuals.

- This finding not only improves our understanding of how the brain works but may one day be applied to treatments.

Researchers have found that the signals in the brains of people with schizophrenia are similar to signals in the brains of people with schizotypal personalities. This discovery opens up new ways of looking at the condition as well as new avenues for treatment.

The study, published in Schizophrenia Bulletin,was carried out by scientists at the University of Nottingham, the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, and Cardiff University. Building off previous research and ideas on personality types going back decades, the study suggests that schizophrenia is not an entirely distinct condition but is instead an extreme variation of a common personality type.

The Schizotypal Personality

The schizotypal personality is characterized by social anxiety, magical thinking, unusual perceptual experiences, eccentric behavior, a lack of close friends, atypical speech patterns, and suspicions bordering on paranoia. These personality traits that, taken together, resemble the symptoms of schizophrenia.

A person with schizotypal personality disorder has these personality traits at a level where they begin to interfere with their lives, such as preventing them from forming close relationships, but they lack the hallucinations or delusions commonly associated with full-blown schizophrenia.1

The similarities between this personality type and the symptoms of schizophrenia interested the researchers. Since previous studies had shown that the electrophysiological response patterns in the brains of schizophrenic test subjects were often strange (the patterns showed a reduced post-movement beta rebound [PMBR] to be precise), the study looked at the brains of healthy patients to see if a person with a schizotypal personality would have similar brain activity.

Eduard Einstein (left) and his father Albert Einstein. Eduard was a brilliant student who wanted to study psychiatry before being diagnosed with schizophrenia at the age of 20. He lived a difficult life afterwards, dying in an institution at the age of 55.

(Einstein: His Life and Universe)

The experiment

The experiment took 112 test subjects and had them answer a questionnaire, similar to others available online, to determine how many features of the schizotypal personality they had. They were then strapped into a magnetoencephalography (MEG) machine to have their brains scanned while they performed a simple motor task.

The volunteers were asked to move their index fingers when given a prompt. The reaction in their brains was recorded. The results were then compared to the answers the test subjects gave in their questionnaires.

As expected, the higher that a person scored on the schizotypal personality test, the more subdued their PMBR brain activity was—just as it is for patients with schizophrenia. This brain activity was particularly associated with scoring high on the parts of the test geared towards reveling the subject’s tendencies to disorganized thinking and difficulty in forming interpersonal relationships.

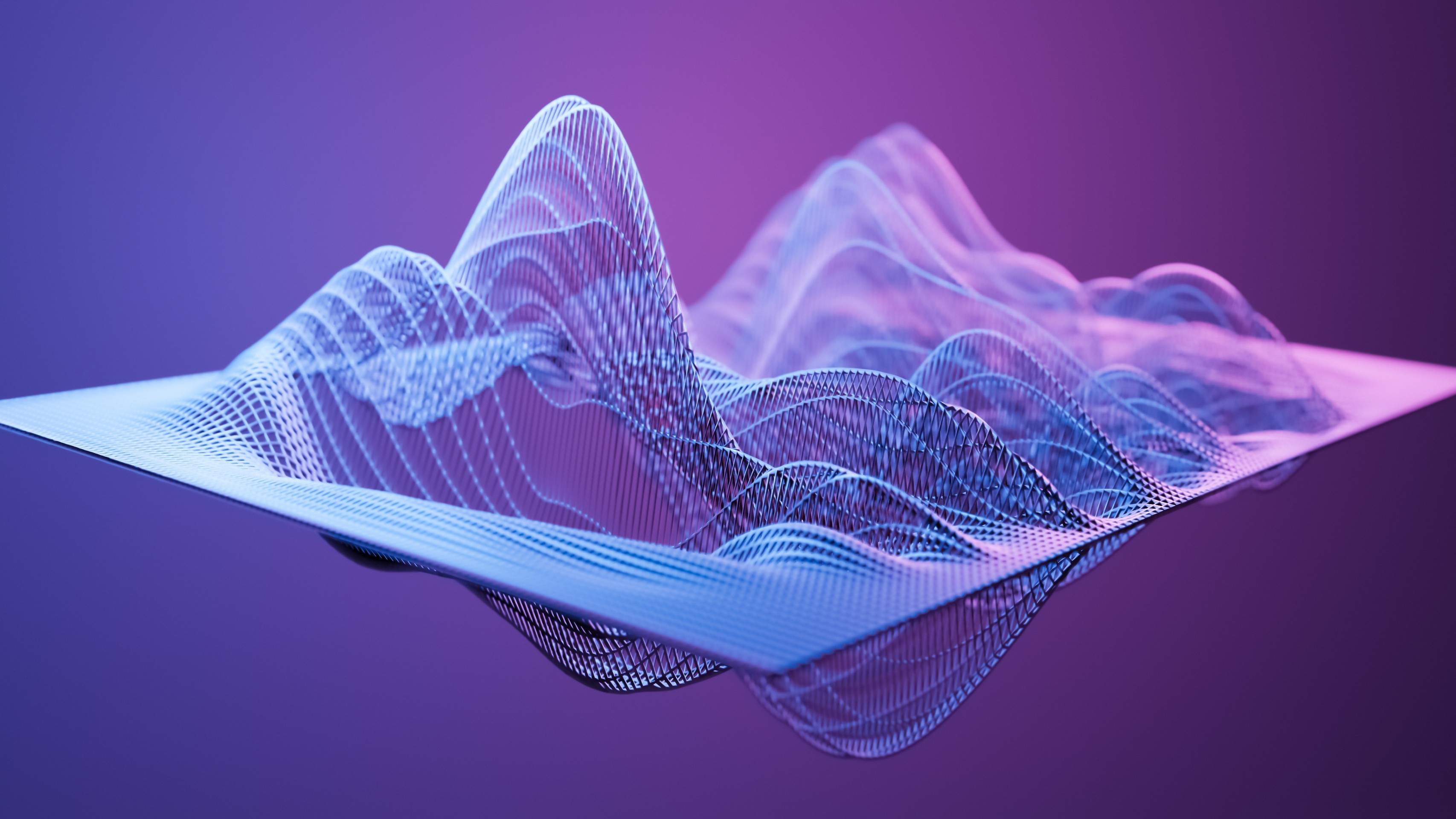

Sample brain scans from the study. Here we see false color images of the brain, with areas that showed higher brain activity during the experiment shown in the most vibrant shades. The top row shows the change above baseline and the bottom shows the change below it. In a test subject with either schizophrenia or many schizotypal traits, the amplitude of the change would be greatly reduced.

(Hunt et al.)

What are the implications of this study?

The authors conclude the study by explaining

The finding that diminution of PMBR, previously reported in schizophrenia, is correlated with the severity of schizotypal features across the range observed in the general population, supports the hypothesis that at least some aspects of schizophrenia lie at the extreme end of a normal personality variant.

This idea, which has been around since the seventies, has recently been given more attention as a result of increasing interest in the concept of viewing mental disorders as existing on a gradient. This new view could lead to a better understanding of schizophrenia and perhaps even better treatments over the long run.

The results might also be of use in reducing the stigma around mental illness, as the study shows that the thought processes of people with schizophrenia are not categorically different from those of many other people. It is a difference of severity, not substance, which seems to separate those suffering from schizophrenia from the people who are merely eccentric.

Of course, more research is needed. At this moment, scientists aren’t sure what neural mechanism even causes this brain activity, let alone how to treat the more extreme manifestations of the reduced activity seen in cases of schizophrenia.

Our understanding of mental illness has changed drastically over the last few decades as old ideas of what counted as mental illness are thrown out, and new ideas step up to replace old paradigms. The results of this study suggest that the brains of patients with this disease are more similar to the minds of healthy people than had previously been thought. While it will take years of more research before any medical advances are made on this information, our understanding of the people who go through life with this condition can be improved today.

1 Schizophrenia is not multiple personality disorder, despite the common misconception.