How President Woodrow Wilson tried to end all wars once and for all

Getty Images

- President Wilson proposed “Fourteen Points” at the end of World War I.

- He wanted an organization created – the League of Nations – to settle international disputes.

- The League was a precursor to the United Nations, but the U.S. never actually joined it.

Coming out of the horrendous calamity of World War I, Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the United States, developed a vision for an international world order that could prevent future war. He was passionate about the creation of the League of Nations, an organization where disputes between countries could be mediated through diplomacy – a precursor to the United Nations. The League was created in 1920 but ironically Wilson couldn’t get his own country to sign on to the pact. Despite that, Wilson’s perseverance in seeking out a new way to ensure communication and collaboration between nations had a tremendously lasting impact and is important to remember, especially as the world teeters on the edge of new conflicts.

Towards the end of World War I, on January 8th 1918, Wilson announced a set of Fourteen Points in a speech to the United States Congress. It was a statement of principles to be considered in peace negotiations that would end the war. A larger goal of the points was to create a new diplomatic order of international cooperation that would prevent another horrific war that ensnared the whole world. Wilson recognized that people don’t always have to agree but need to be able to engage with opposing viewpoints in a way that is not confrontational and destructive. The principles provided for the creation the League of Nations which would help mediate disputes and keep peace.

“XIV. A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.” – from “Fourteen points” by Woodrow Wilson.

1918 cartoon by E.A. Bushnell of Kaiser Wilhelm considering Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

Wilson’s speech was regarded as idealistic by some but became an important piece of propaganda for the Allied powers, dropped as leaflets behind enemy lines. Besides conveying the vision of a post-war order, the points were used to convince Germans that they would get a just settlement at the war’s end. The reality is that this didn’t quite pan out as the differences between the eventual Treaty of Versailles and the promises of Wilson’s Fourteen Points angered the Germans. The resentment likely carried over into the rise of National Socialists (and eventually Nazis), think historians.

About a month later, on February 11th, Wilson gave another speech in front of the joint session of Congress, elaborating on his vision:

“We are indomitable in our power of independent action and can in no circumstances consent to live in a world governed by intrigue and force, ” said Wilson. “We believe that our own desire for a new international order under which reason and justice and the common interests of mankind shall prevail is the desire of enlightened men everywhere. Without that new order the world will be without peace and human life will lack tolerable conditions of existence and development. Having set our hand to the task of achieving it, we shall not turn back.”

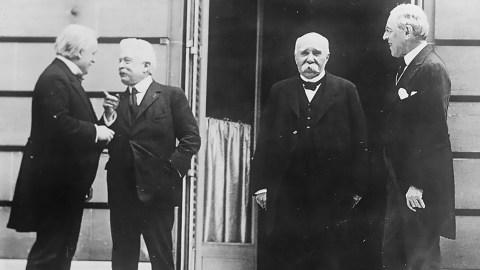

Exemplifying Wilson’s new international order, the League of Nations actually came into existence as a result of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The war-ending agreement was negotiated by diplomats from 32 countries, including the leaders of the “Big Four” comprised of President Wilson, the Prime Minister of France Georges Clemenceau, UK’s Prime Minister David Lloyd George and the Italian PM Vittorio Emanuele Orlando.

“Big Four” world leaders at Paris Peace Conference. May 27, 1919. From left to right: Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Premier Vittorio Orlando, Premier Georges Clemenceau, and President Woodrow Wilson.

Courtesy: Library of Congress

The primary goal of the League of Nations, officially founded on January 10th, 1920, was to prevent wars through collective security and disarmament, while resolving international disputes by arbitration and negotiation. It also was to take aim at issues that still sound quite relevant today – human and drug trafficking, labor issues, treatment of native people and minorities, the arms trade and global health concerns, among others.

As of February 1935, the League of Nations counted 58 members. Notably missing among them? The United States. Despite his best efforts to promote the idea back home, President Wilson, who was actually awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919 for his work in securing peace, wasn’t able to convince the U.S. Congress to make the country join this new international body. Wilson ran into concerns which you can hear around the halls of Congress even today – that the country will become the world’s policeman and lose its sovereignty.

“I can predict with absolute certainty that within another generation there will be another world war if the nations of the world do not concert the method by which to prevent it” – Woodrow Wilson, 1919.

The first session of the League of Nations in the Salle de Reforme in Geneva. 1920.

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

An important side note is that President Wilson fell ill while on an intense 8,000-mile tour to promote the League of Nations and decry isolationism across the U.S., ultimately suffering a stroke.

Wilson’s efforts can be regarded as quixotic but his own words shed light on why his goal was not only important at the time but should be considered as successful – he saw what the world needed and future generations brought about some version of such a vision:

“There is only one power to put behind the liberation of mankind, and that is the power of mankind,” said Wilson in 1919. “It is the power of the united moral forces of the world, and in the Covenant of the League of Nations the moral forces of the world are mobilised… And what do they unite for? They enter into a solemn promise to one another that they will never use their power against one anther for aggression; that they never will impair the territorial integrity of a neighbour; that they never will interfere with the political independence of a neighbour; that they will abide by the principle that great populations are entitled to determine their own destiny and that they will not interfere with that destiny; and that no matter what differences arise amongst them they will never resort to war without first having done one or other of two things – either submitted the matter of controversy to arbitration…. or submitted it to the consideration of the council of the League of Nations…”

The lack of U.S. involvement, along with absence of its own army and not getting whole-hearted support from the key powers were all factors that eventually doomed the League of Nations. Clearly, while extremely hopeful in purpose, it wasn’t successful in preventing another World War. The United Nations ultimately replaced the League of Nations after World War II as the pre-eminent entity for world diplomacy, incorporating several agencies and organizations founded by the League.

The Gap in the Bridge. Cartoon about the absence of the U.S. from the League of Nations. 1919.

Punch Magazine.