The unexpected first jobs of famous scientists

- First jobs can have often contradictory expectations and feel like an odd fit for your talents.

- If you feel that way, you’re not alone: Isaac Newton once worked as a farmer.

- One tip for your first job: be an observer of people and your environment.

The great American writer William Faulkner used to work in a post office. Whoopi Goldberg was a morgue beautician. Colin Powell — former Secretary of State and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — worked in a baby furniture store.

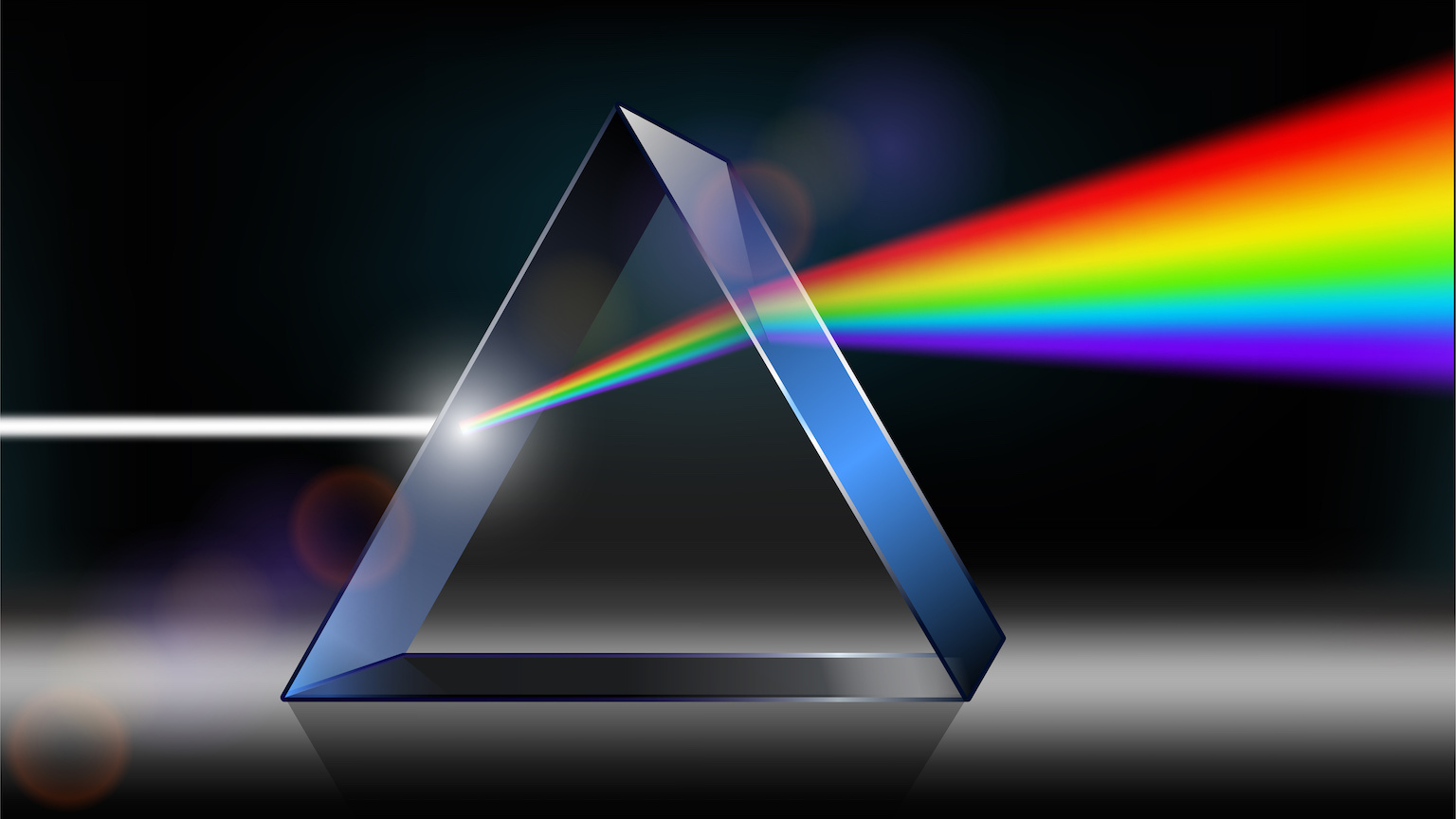

This holds true for some famous scientists, too. For instance, Isaac Newton — the man who helped develop calculus, the laws of motion, gravity; who helped establish the foundations of classical mechanics; who built the first ‘practical’ telescope and developed a theory of the color spectrum (and whose papers you can read online here) — went through a period of life where his mother urgently and dearly wished him to be a farmer.

With his mother divorced for a second time when Isaac was nearing 16, the budding mathematician was ordered to quit school and come home to work as a farmer. By all available reports, he did not make a success of it.

The conditions and profitability of farming in the U.K. in the 17th century didn’t necessarily make his work any easier either. The Agriculture Revolution was — at best — just beginning to stir, and, as Joan Thirsk noted, grain prices “rose by only two percent between 1640 and 1750. Grain fell by 12 percent, and wool by 33 percent.”

Marie Curie. Photo source: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Another scientist who had a job different from the one they ended up with was Marie Curie. Marie Curie — the first woman to win the Nobel Prize for her research on radioactivity (and the first person and first woman to win the Nobel Prize twice) — worked as a governess when she was younger, where she was in charge of the children of an “agriculturist who ran a beet-sugar factory in a village 150 kilometers north of Warsaw. What can we begin to suss out from the discrepancy between someone’s first job and the job for which they eventually became ‘known?’ Consider the advice offered up by Jodi Glickman in Harvard Business Review:

“Be an observer of people and your environment. What is the team dynamic like? Why do people love (or hate) the boss? Who can you emulate or model yourself against as you move through the ranks? … Who wields power and influence and who is relegated to the sidelines? How do people who always solve problems do it?”

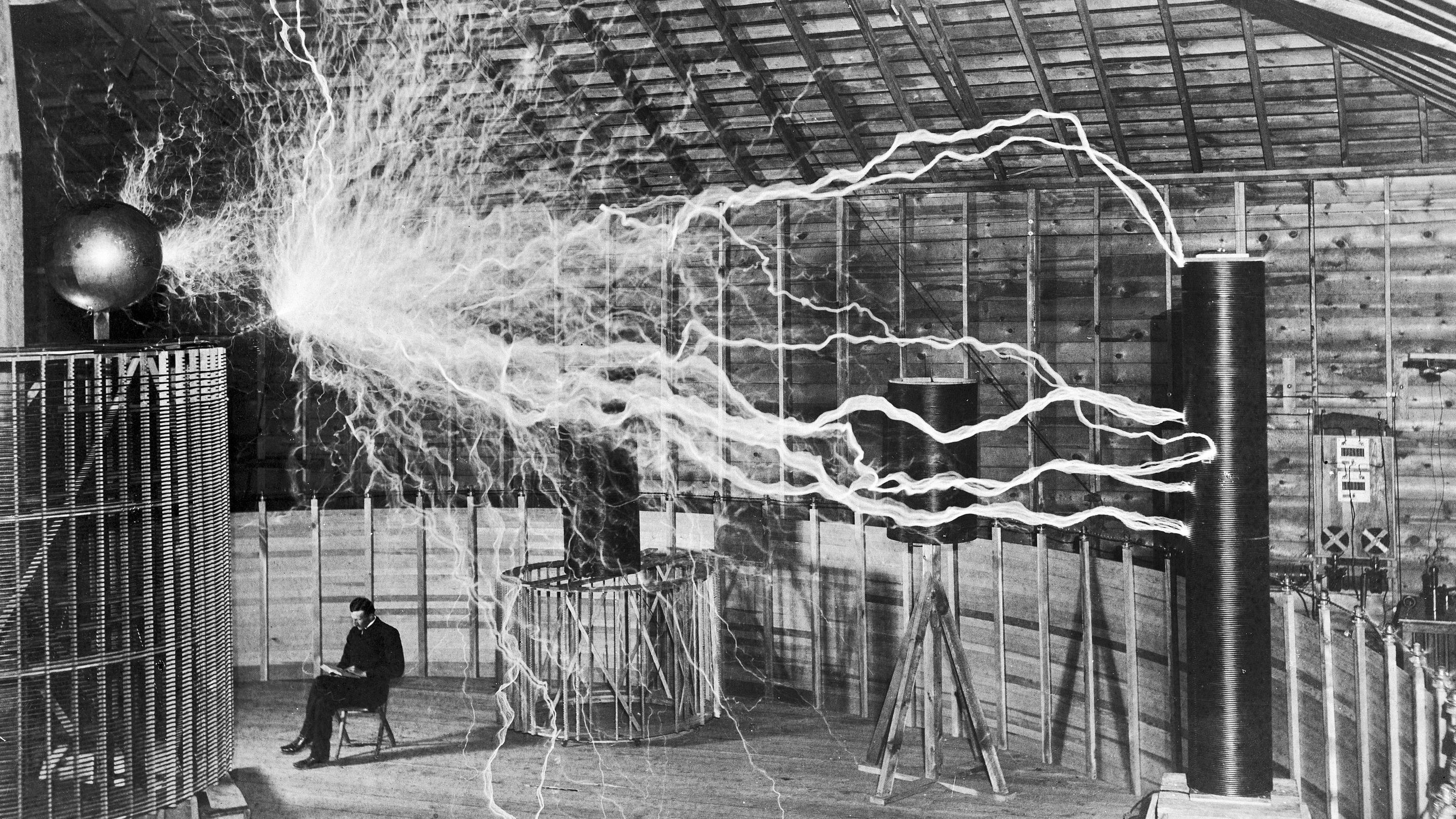

This becomes an apt paragraph when we consider that Gregor Mendel — who discovered the basic principles of heredity — worked as a gardener. It’s apt when we consider that Michael Faraday — who established how magnetic fields reacted to electricity and light; who worked to catch particles in a vacuum and much — was an apprentice to a bookseller and a bookbinder (that is how he began his education).

So there’s a degree to which it doesn’t matter if your first job was — as someone mentioned on Reddit— “collecting and buffing chicken shit off eggs.” It’s about what you observe. And there’s a degree to which the job will simply feel odd, too, and the degree to which you’ll evolve.

In 2014, the New York Times ran a piece exploring how certain people navigated their first jobs and many of them discovered contradictions of who they were then compared to who they are today. Some people were too polite. Some had showed too much initiative. Some didn’t dress as well as they could have. Some dressed too well —as if they were already aiming above their station. Their past behaviors didn’t ultimately reflect who they became.

For example: consider the case of the young man who couldn’t get a recommendation from his professors because he kept interrupting classes, kept “approaching the blackboard to finish equations without being asked,” was alternatively indifferent at other times to participating altogether and so — as a result — ended up getting a job at a Swiss patent office. That man was Albert Einstein.

All of this said, sometimes we follow a circuitous-seeming path. Complex dynamics often shape an individual’s life.