Nuclear-powered Mars rover to search for old life, prepare for human life

NASA/JPL-Caltech

- NASA recently unveiled the final details of the Mars 2020 rover mission.

- As yet unnamed, the Mars 2020 rover will launch in July of that same year. It’s primary mission will be to search the planet for signs of microbial life.

- However, the rover also contains instrumentation that will enable it to prepare for future human life, including a device to produce oxygen from Mars’ CO2 atmosphere.

Once every 26 months or so, Earth’s and Mars’ elliptical, off-kilter orbits align in just the right way to bring the two planets together as closely as possible, with a mere 35.8 million miles to separate them (or 57.6 million kilometers).

That’s why Mars 2020, the successor to the Curiosity Rover, is set to launch in July of 2020, when Mars is at its closest with Earth. Since its mission was first announced in 2012, the Mars 2020 rover has been designed and developed to seek out signs of ancient microbial life and even prepare Mars’ inhospitable surface for future manned missions.

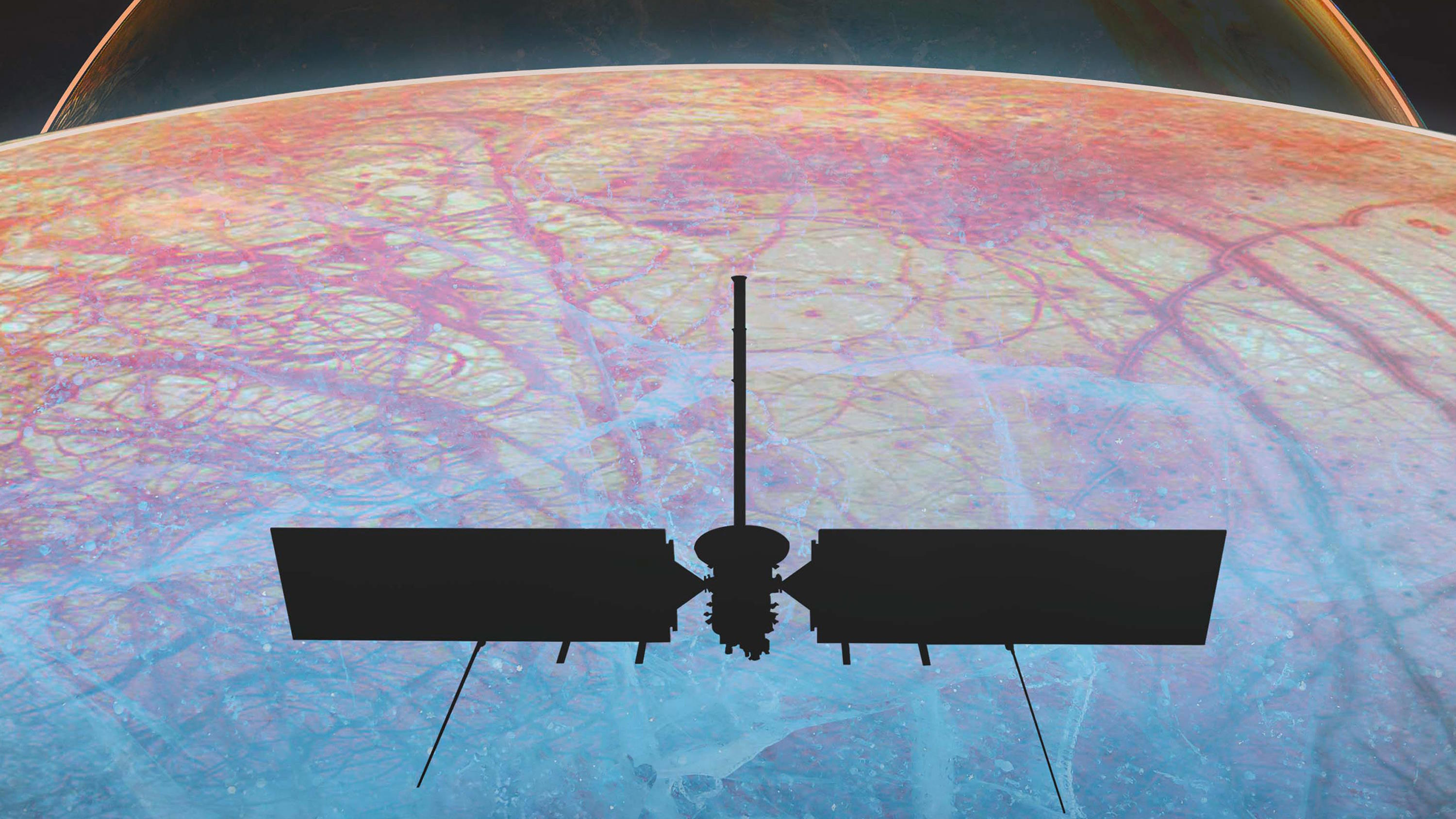

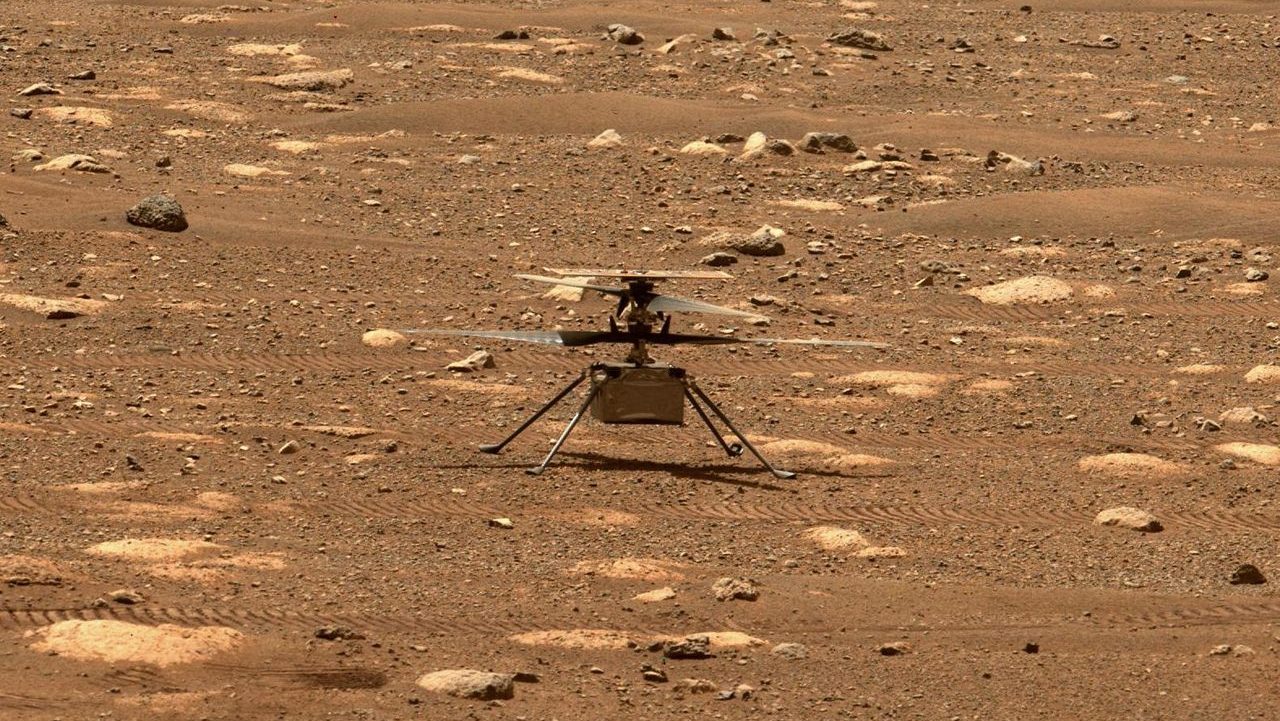

An engineer works on the solar-powered drone that will be affixed to the Mars 2020 rover.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

What will the Mars 2020 rover look like?

For the most part, the as-yet unnamed Mars 2020 rover is based on the design of the Curiosity rover. Curiosity’s original mission was only meant to last for two years, and yet the rover has been functioning and conducting science for more than seven years now. Re-using this robust design helps to cut down costs and risks for the Mars 2020 rover.

“It’s designed to seek the signs of life, so we’re carrying a number of different instruments that will help us understand the geological and chemical context on the surface of Mars,” deputy mission leader Matt Wallace told AFP.

Mars 2020 will carry 10 different instruments, including 23 cameras, microphones to listen to the rover’s performance and identify any possible mechanical issues, an X-ray spectrometer, radar, a solar-powered drone, and more.

Like Curiosity, these instruments will be powered by a miniature nuclear reactor in the Mars 2020 rover, but the new rover will have more durable wheels (you may remember occasional news articles bemoaning holes and dents in Curiosity’s wheels). Mars 2020 will also include an improved landing system, dubbed Terrain-Relative Navigation (TRN). This system will help the rover detect and avoid hazardous terrain during its descent and enable it to land within 130-foot area compared to Curiosity’s 53.4-mile landing area.

This map shows Jezero crater, where Mars 2020 will touch down, as well as the landing sites of all other spacecraft to visit Mars.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Searching for ancient life

This ability to precisely choose a landing spot is critical to Mars 2020’s primary goal, which is to search for signs of ancient microbial life. When searching for microfossils on a barren planet whose surface is exposed to cosmic rays and the elements, location is key. That’s why Mars 2020 will touch down in the Jezero crater, an 820-foot crater that used to be a lake 3.5 to 3.9 billion years ago.

Because a river delta used to flow through the ancient lake, a significant amount of sediment has collected within the crater. Specifically, NASA researchers hope to find hydrated silica, a crystalline mineral that has preserved signs of life on Earth for billions of years, hopefully having done the same on Mars.

Using a drill to gather cored samples of this material, Mars 2020 will then set aside caches on the surface of Mars. Future missions will collect these caches and deliver them back to Earth, where researchers will be able to analyze the samples in lab equipment too bulky to transport to the Red Planet.

“We are hoping to move fairly quickly. We’d like to see the next mission launched in 2026, which will get to Mars and pick up the samples, put them into a rocket and propel that sample into orbit around Mars,” said Wallace.

“The sample would then rendezvous with an orbiter and the orbiter would bring the sample back to the Earth.”

Preparing for new life

The other major thrust of Mars 2020’s mission will be to pave the way for future human missions and study Mars’ potential for habitability. The entry, descent, and landing of the rover will be carefully studied to improve future touchdowns, and the rover’s many sensors will work toward understanding the environmental conditions that astronauts will face when living and working on Mars.

Excitingly, the rover will also include a device called MOXIE (Mars Oxygen In-situ Resource Utilization Experiment). This experimental technology will suck in CO2 — which composes 96 percent of the Martian atmosphere — remove dust and other contaminants, and convert the CO2 into a small amount of oxygen.

The MOXIE device on Mars 2020 will only output about 22 grams of oxygen per hour, but if it succeeds, NASA researchers hope to land a 100-times larger MOXIE device on Mars capable of producing two kilograms of oxygen per hour.

This oxygen could be stored in tanks to be used as life support for future astronauts and for fuel for either autonomous or manned return flights to Earth.

Over the next few years, we can look forward to hearing about Mars 2020’s experiments, hopefully learning whether or not life came into existence twice in the same solar system. As those years stretch into decades, the success of Mars 2020 will set up future manned missions to Mars, possibly as soon as the 2030s.