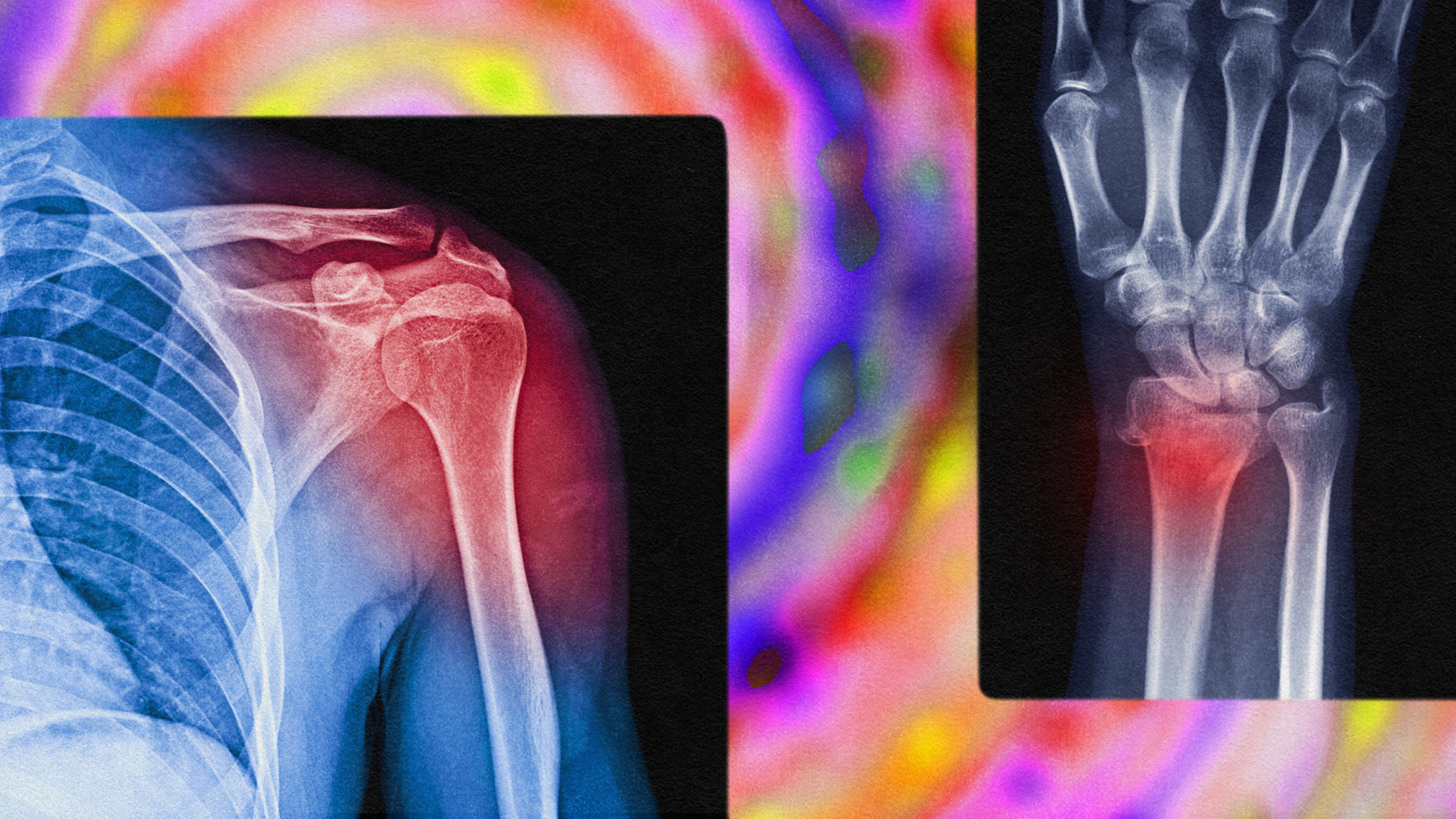

Can psychedelics help treat pain?

Photo by Joe Amon/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images

- Pharmacology professor Richard J. Miller is hopeful for the resurgence in clinical studies of psychedelics.

- Ibogaine, used in France for decades, is making a comeback in potentially helping curb addiction and treat pain.

- Psychedelics were deemed illegal for political and not medical reasons, an error we are reinvestigating.

With all the hype regarding the potential for psychedelics to help treat anxiety and depression, with the potential to replace or coexist with SSRIs, there are yet more realms hallucinogenic substances could aid in. Whereas psilocybin and MDMA are showing positive results in sufferers of mental pain, a formerly sanctioned drug, ibogaine, is making a comeback in pain management and addiction circles.

As with other psychedelics, ibogaine was swept up in Richard Nixon’s crusade against minority and freethinking populations in the late sixties and deemed a Schedule 1 drug in 1971. Yet from 1939 to 1970, ibogaine was used in French psychotherapy under the trade name Lambarene, writes Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine pharmacology professor Richard J. Miller.

As with the entire class of substances, the scheduling of ibogaine was a political, not medical, decision. As Miller recently told me from his office in Chicago,

“The drugs, at the federal level, are Schedule 1 drugs, which means that they have absolutely no medical utility whatsoever and are incredibly dangerous. People think that the reason that they’re in that schedule is based on some kind of reasonable science or other understanding of what they do rather than just some complete bullshit, which is what it is.”

I reached out to Miller after reading his excellent history on pharmacology, Drugged: The Science and Culture Behind Psychotropic Drugs (the full transcript is here). While he’s spent decades clinically studying drugs, the narrative shines when Miller discusses the cultural stories about how and why we seek to alter our consciousness, be it through caffeine or magic mushrooms.

There is no greater substance for the treatment of pain—Miller’s clinical speciality—than opiates. Drugs like morphine reduce the amount of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, causing smaller muscle contractions. The inhibition of these neurotransmitters, combined with opiate receptors in our midbrain implicated in our reward center, help to make us feel better—and get us addicted.

Which is the rub: the greatest pain reliever yet discovered is highly addictive. The novelist Amitav Ghosh wrote an entire trilogy about the political and cultural effects of the opium trade; Thomas de Quincy famously defined a genre when penning a book about his addiction to laudanum. Today, in America, we have our own opium war in the form of fentanyl. The side effects are, as we are collectively experiencing, disastrous.

Just as the mental health industry needs a better solution than SSRIs, which are remarkably effective in the short-term but also deadly over the span of years and decades, physical pain management needs a revolution. The hallucinogenic shrub, Tabernanthe iboga, might provide relief.

Though the cradle of civilization, Africa is relatively void of hallucinogens. One of the strongest utilized comes via the main alkaloid in T. iboga, ibogaine. Iboga communities exist in Gabon, Cameroon, and Zaire, where adherents either eat or drink the yellow root to experience visions in order to, as the Bwiti phrase it, “break open the head.”

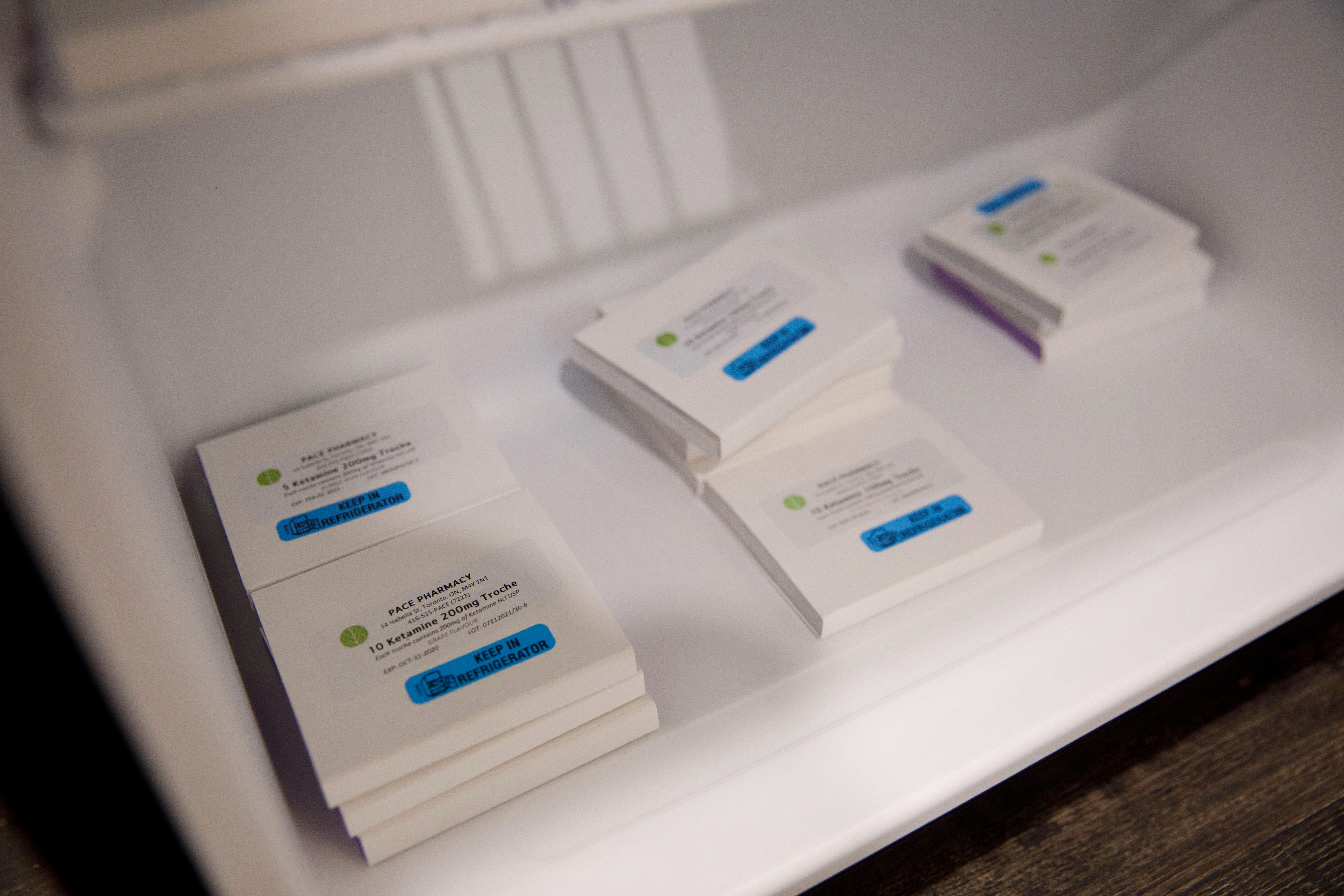

Iboga made its way to France in 1864, first appearing in the scientific literature two decades later. Ibogaine was extracted in 1901. Howard Lotsof, a heroin addict in New York City, discovered ibogaine in the sixties and self-experimented to curb his addiction. It worked. He persuaded a pharmacologist in Albany to test the substance in morphine-dependent rats, which also “appeared to work,” according to Miller. The researchers also noticed positive results getting the rats off of cocaine, alcohol, and nicotine.

The Albany team then worked with a team at the University of Vermont in an attempt to synthesize an ibogaine analog. Even the ceremonial users in Africa knew that the root is toxic; swallow too much and death ensues. The team, searching for a less toxic substance, synthesized 18-methoxycoronaridine (18-MC). Ibogaine has been used in addiction treatment for decades even as it has been predominantly illegal.

After Phase 1 trials, the funding was exhausted. A new organization, MindMed, is currently planning Phase II trials this year. So far, 18-MC does not appear to have the hallucinogenic effects of ibogaine, which might prove important if it is ever developed for widespread addiction treatment or pain management. Ibogaine notably causes cardiovascular problems in some users; 18-MC might also skirt that issue.

This also solves the patent problem. Given the money required in R&D of a new drug—over $1 billion, in some cases—it’s challenging for pharmaceutical companies to profit from new drugs. At the same time, as Miller assures me, “they are definitely making money.” That much is obvious given the billions of dollars that the Sacklers profited from helping create the opioid epidemic, the very reason we so desperately need a better solution now.

Yet it also begs the question: why are we in so much pain? The reasons are varied: sedentary lifestyles; dramatic income gaps; social media’s role promoting the constant yearning for youth; intensely laborious jobs; being overworked and underpaid. If the revolution in pharmacology last century taught us one thing, it’s that humans will seek pills to cure problems instead of addressing the root cause. As Miller and I discussed, the distance between physical and emotional pain isn’t necessarily as far as believed.

“When you use the word pain, which you just used in a certain way, pain could mean things like somebody’s emotional pain to a clinician. However, it’s usually much more involved in actual physical pain. That’s the kind of thing that people are usually talking about when they’re talking about trying to replace opiates for treatment of those kinds of things. On the other hand, there is emotional pain. On the third hand, there is actually a connection between physical pain and emotional pain. We know about how different parts of the brain connect with each other. So there are a lot of levels that you can attack pain.”

While it’s hard to find a bright side to the opioid epidemic, Miller says one positive is that governmental agencies are taking pain management more seriously. That covers mental and physical pain—there’s a reason the FDA has labelled both psilocybin and MDMA as breakthrough therapies. Regardless of the type of pain, and knowing there is a meeting point between the two, psychedelics are showing efficacy in many aspects of treatment. This is a field of research whose time has come.

—-

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook. His next book is Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.