Researchers discover dozens of existing drugs with anti-cancer properties

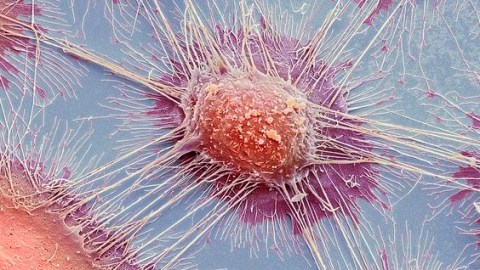

Flickr user Weining Zhong

- A recent study identified nearly 50 different existing drugs with anti-cancer properties.

- Learning about these previously unrecognized properties is critical — since drugs like these have already been approved for human consumption, they can be brought to the market and applied in cancer treatment faster.

- The study also identified novel mechanisms of action that could serve as the focus of future studies.

The anti-inflammatory drug tepoxalin, primarily used for treating osteoarthritis in dogs, was recently discovered to have more uses than just helping old dogs move better. The same was found for the alcohol dependence drug disulfiram as well as vanadium, which was originally designed to treat diabetes.

Researchers discovered that these and nearly 50 other drugs developed with a variety of purposes in mind actually have previously unrecognized cancer-fighting properties. “We thought we’d be lucky if we found even a single compound with anti-cancer properties, but we were surprised to find so many,” said Professor Todd Golub, co-author of a recent paper describing the work in the journal Nature Cancer.

The idea that a drug developed for one purpose can have other benefits is nothing new. Famously, one doctor’s observations of his patients in 1948 led to the discovery that aspirin was not only an excellent painkiller but also helped to prevent heart attacks.

These incidental uses inspired the creation of the Broad Institute’s Repurposing Hub, which contains a database of thousands of compounds approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for one use and yet may have others. The recent study was the largest to date to make use of this database.

Using cells from 578 different kinds of cancer, the researchers tested 4,518 different drugs, finding that nearly 50 had previously unrecognized cancer-fighting properties. Not only does this diversify our toolkit when treating cancer, but it also means that we can quickly bring these solutions into treatment. All the tested drugs have already been approved by the FDA for human consumption, and many are already in mass production.

Revealing new cancer-fighting capacities

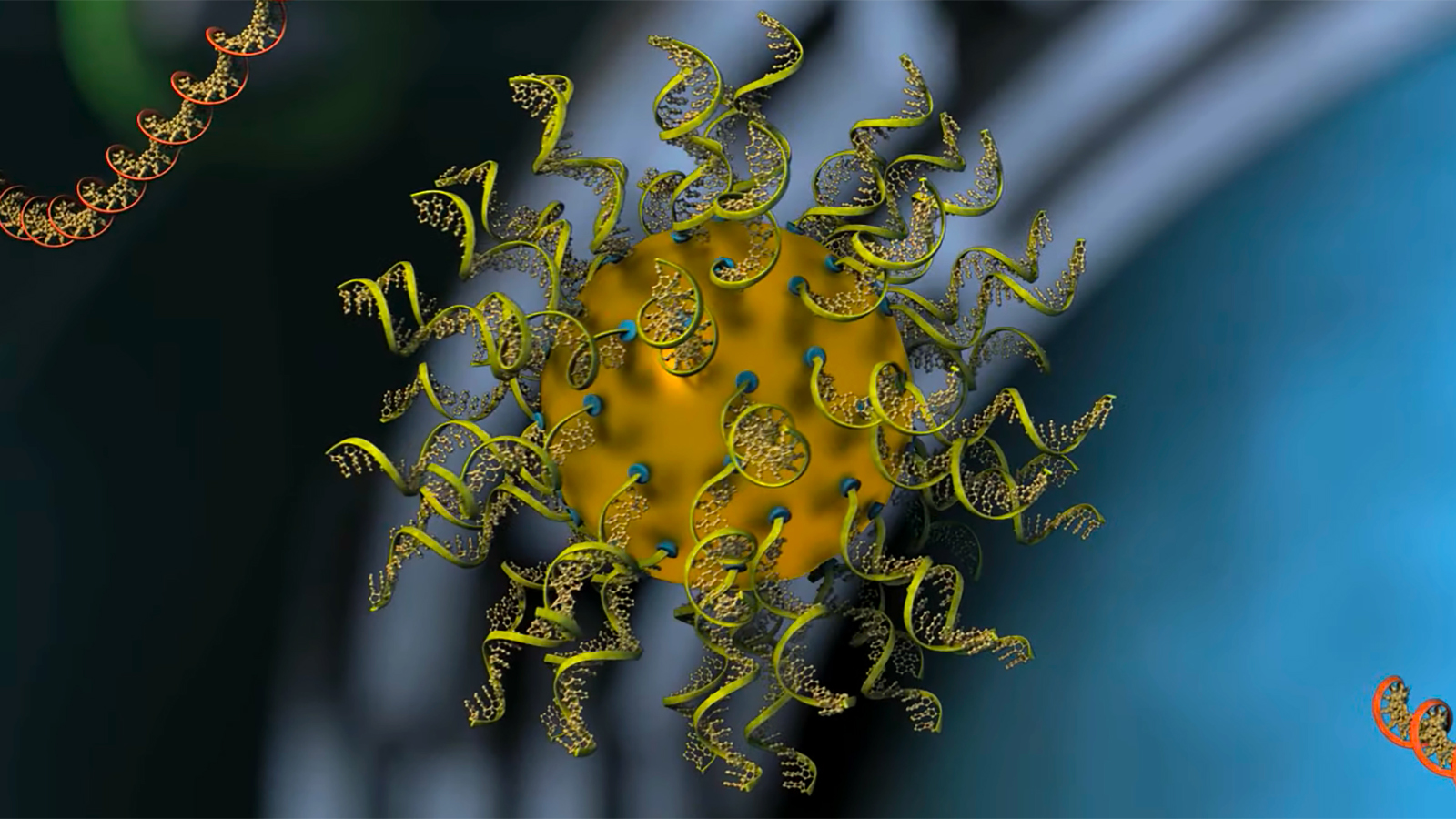

In order to rapidly test the different cancer cell lines against a compound, the researchers used a method called PRISM (profiling relative inhibition simultaneously in mixtures), which consists of adding a short DNA “barcode” to the cells that enabled the researchers to test several cell lines at once. After exposing a group to a given compound, the researchers could measure the cells’ survivability rates based on these barcodes.

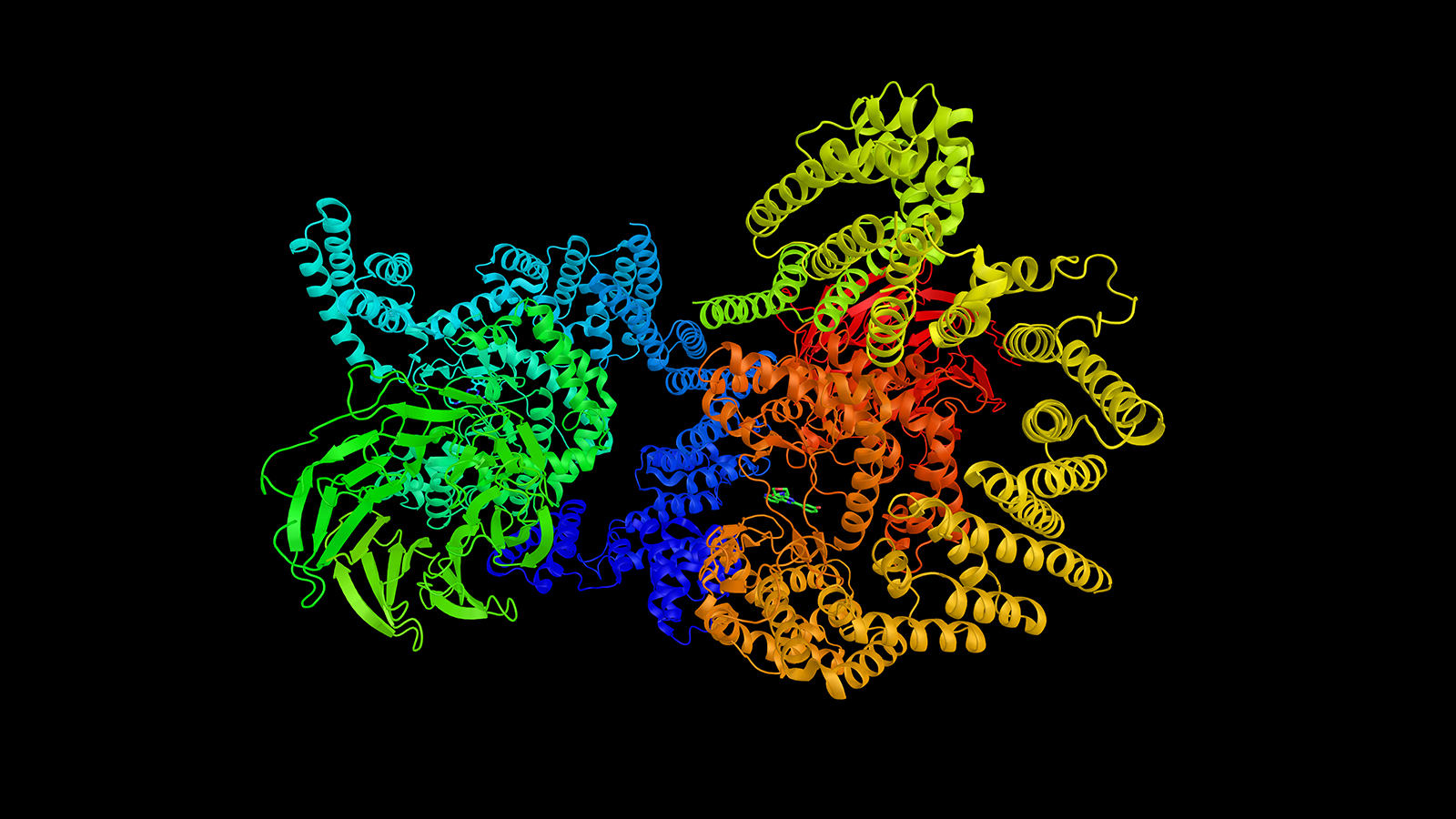

Not only did this reveal different compounds’ cancer-fighting properties, it also revealed unique mechanisms of action. “Most existing cancer drugs work by blocking proteins, but we’re finding that compounds can act through other mechanisms,” said study co-author Steven Corsello. For instance, nearly a dozen drugs killed cancer cells by targeting the interaction between two proteins commonly expressed in cancer cells, rather than the proteins themselves. Another drug, tepoxalin — the osteoarthritis drug for dogs — was found to target some unknown feature of cells that overexpressed the protein MDR1 (a protein that provides cancerous cells with resistance to chemotherapy drugs), providing a subject for future study.

Other drugs were discovered to kill cells based on their expression of biomarkers, meaning that the patients who would benefit the most from those drugs could be quickly identified. Disulfiram, the alcohol dependence drug, was found to kill cells with low expressions of metallothionein proteins, for example. Vanadium, the diabetes drug, killed cells expressing a certain sulfate transporter protein. By looking for low levels of metallothionein or high levels of this sulfate transporter, doctors can quickly assess whether a patient will respond well to treatment using these drugs.

The Broad Institute’s Repurposing Hub is growing rapidly, containing thousands of more compounds now than when this study was initially carried out. Not only does work like this identify useful drugs and future subjects of research, but it also acts as proof that many other compounds out there have useful applications in treating conditions other than those they were designed for. This study focused on treating cancer, but any number of alternative conditions could be the focus of future research. It could be the case that the answers to many of our problems are sitting right under our noses.