A longer life often means a worse death

- A new study out of Sweden finds that people who live longer often spend more time undergoing end-of-life care, suggesting that their deaths are more drawn out than people who die younger.

- Medical care at an advanced age often extends life without significantly improving one’s quality of life.

- The study draws further attention to the gap between lifespan and healthspan. In many developed societies, people are living longer but also spending a higher proportion of their lives living in poor health.

Humans are living longer than ever before. Since 1950, global average life expectancy has risen from 47 to 73. This remarkable gain has been won through reducing poverty and eradicating disease, among other humanitarian advances. But in countries whose citizens are now living to advanced ages in the 80s and beyond, a complicated question must now be asked: Are we actually extending life or merely prolonging death?

Extending life or prolonging death?

A team of researchers from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden confronted this query head-on with a study recently published in the American Journal of Public Health. Demographer Marcus Ebeling and his colleagues utilized large public databases to track the course of all deaths of individuals aged 70 and over in Sweden between 2018 and 2020, focusing on patients’ final 12 months. Chiefly, they wanted to know how most elderly individuals die.

Are their deaths short and sudden or long and drawn out? Do they die at home, physically able and mentally sharp until the end? Or do they die in a facility, impaired and care-dependent in their final years, essentially wasting away? Tragically, it increasingly seems to be the latter.

“Two-thirds of all deaths followed a trajectory with extensive elder care utilization throughout the last year of life, and at least half additionally showed extensive medical care utilization,” they found. “Most deaths today do not comply with what is often referred to as a ‘good’ death.”

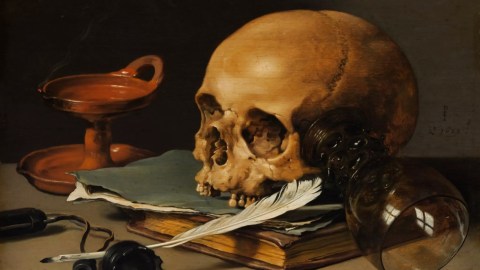

What constitutes a good death? “Retaining control, being pain-free, having the choice of the place of death, and not having life prolonged pointlessly are principles that have been mentioned, among others,” the researchers wrote.

Ebeling and his colleagues also found that prolonged end-of-life care was increasingly common over the age of 83, Sweden’s life expectancy, suggesting that individuals graced with a longer life are more likely to have a drawn out death, potentially filled with medical procedures and physiological burdens.

Lifespan vs. healthspan

The finding calls further attention to the frequently discussed gap between “lifespan” and “healthspan.” Lifespan is how long someone lives; healthspan is how long someone lives in good health, free from chronic disease and disability. Ideally, they should be nearly equal. In actuality, as human lifespan has rapidly grown over the past half-century, healthspan has not kept up. Analyses suggest a present gap of 10 to 15 years between them in the U.S. That’s more than a decade on average of people living in poor health, often at the twilight of their lives. In keeping with Ebeling’s study, this suggests that most people are in declining health prior to death.

And unfortunately, what a lot of end-of-life care tends to do is boost lifespan, with little benefit to healthspan. Drugs and procedures that treat underlying medical conditions in the elderly are often hamstrung in how much “health” they can truly restore. Ultimately, the best way to boost healthspan and hopefully remain independent until the very end is to prevent debilitating conditions from ever cropping up in the first place. That means eating right, refraining from smoking, drinking alcohol in moderation, maintaining social connections, challenging your mind, and above all, remaining physically active. And it means maintaining these habits even into old age.

The major takeaway is that to give yourself the best chance at a good death, do the things that will help you live a fit life.