Zircon in a meteorite opens the door on Mars’ past

Credit: Deng, et al./University of Copenhagen

- A meteorite from Mars unexpectedly contains zircons that reveal the planets history.

- The rock likely comes from one of the solar system’s tallest volcanoes.

- Analyzing the zirconium required smashing some very expensive rock.

Just last week, we wrote about one lab’s conclusion that water may be a common byproduct in the formation of rocky planets. This week, the same lab has announced that the very same Martian meteorite that led to that earlier finding has yet another secret to reveal: It contains lots of zircons, minerals thought to be scarce on Mars. Having so many now is “like opening a time window into the geologic history of planet ,” according to senior author of both studies Martin Bizzarro from the GLOBE Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

Earth zircon in gem form atop calciteCredit: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com/Wikimedia

“We were quite surprised and excited when we found so many zircons in this Martian meteorite,” says Bizzarro. “Zircon are incredible durable crystals that can be dated and preserve information that tell us about their origins.” Zircons are a rarity on Mars’ surface — which resembles the crust beneath Earth’s ocean floors — and so scientists have not been expecting to find much of the mineral.

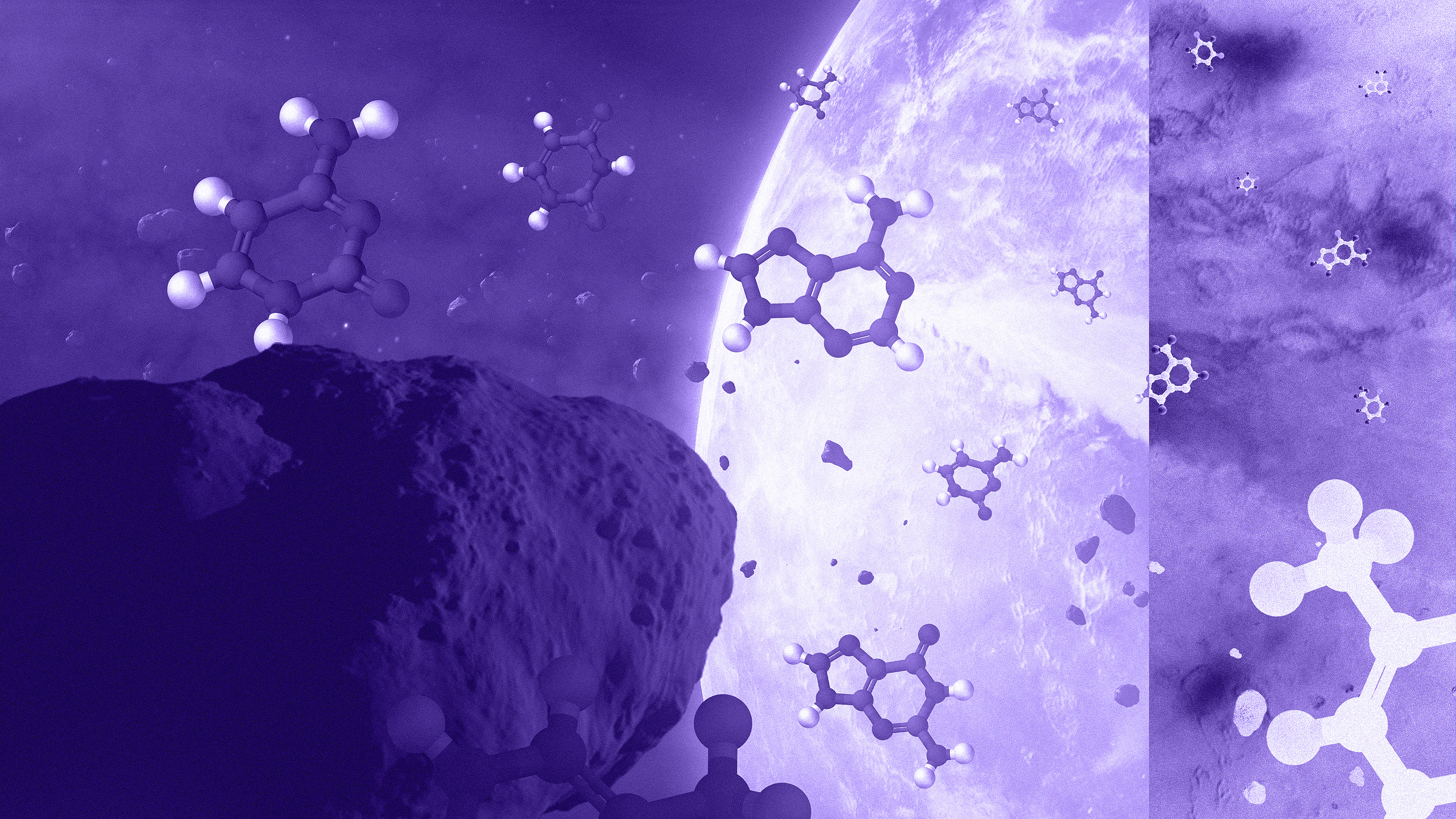

What makes this so intriguing, Bizzarro explains to the Danish National Research Foundation, is that zircon “functions as a small time capsule because it obtains and saves information about the environment as well as when it was created. In this case a time capsule with hafnium, which comes from Mars’ early crust, which existed around 100 million years before the oldest zircon in Black Beauty was created. Thus, Mars got an early start in comparison with Earth, whose solid crust was created much later.”

NWA 7533

Big Think readers may recall that the meteorite — known as “Black Beauty,” though its official name is “Northwest Africa 7533” — cost the university $500,000 dollars for 50 grams of its 319.8-gram volume. As such, deciding to perform any sort of analysis that requires damaging the precious rock is not a decision taken lightly, as when, say, zircons are found in the stone.

“One of the big challenges,” says Bizzarro, “has been that the zircons in Black Beauty are extremely small. This called for a courageous strategy: We crushed our precious meteorite. Or to be precise: We crushed 5 grams.”

The decision paid off, says Bizzarro: “Today, I’m glad we chose that strategy. It released seven zircons, one of which is the oldest known zircon from Mars. And from the zircons and their content of hafnium, we can now conclude that the crystallization of the surface of Mars went extremely fast: already 20 million years after the formation of the solar system, Mars had a solid crust that could potentially could house oceans and perhaps also life.”

Eventually, the team would crush 15 grams of Black Beauty, extracting 60 zircons.

The oldest Martian zircon found so farCredit: Martin Bizzarro/University of Copenhagen

“Zircon is a very solid mineral that is ideal for making such an absolute dating of time. In this regard, zircon can be used as a portal to pinpoint a time frame for the history of crust formation on Mars.” Dating of Black Beauty’s zircons shed new light on the planet’s history. Most of the minerals were dated back to roughly 4.5 billion years ago, the earliest days of the planet.

Unexpectedly, though, some of the zircons were more recently formed, a period from about 1,500 million years ago to 300 million years. “These young ages were a great surprise,” recalls Bizzarro.

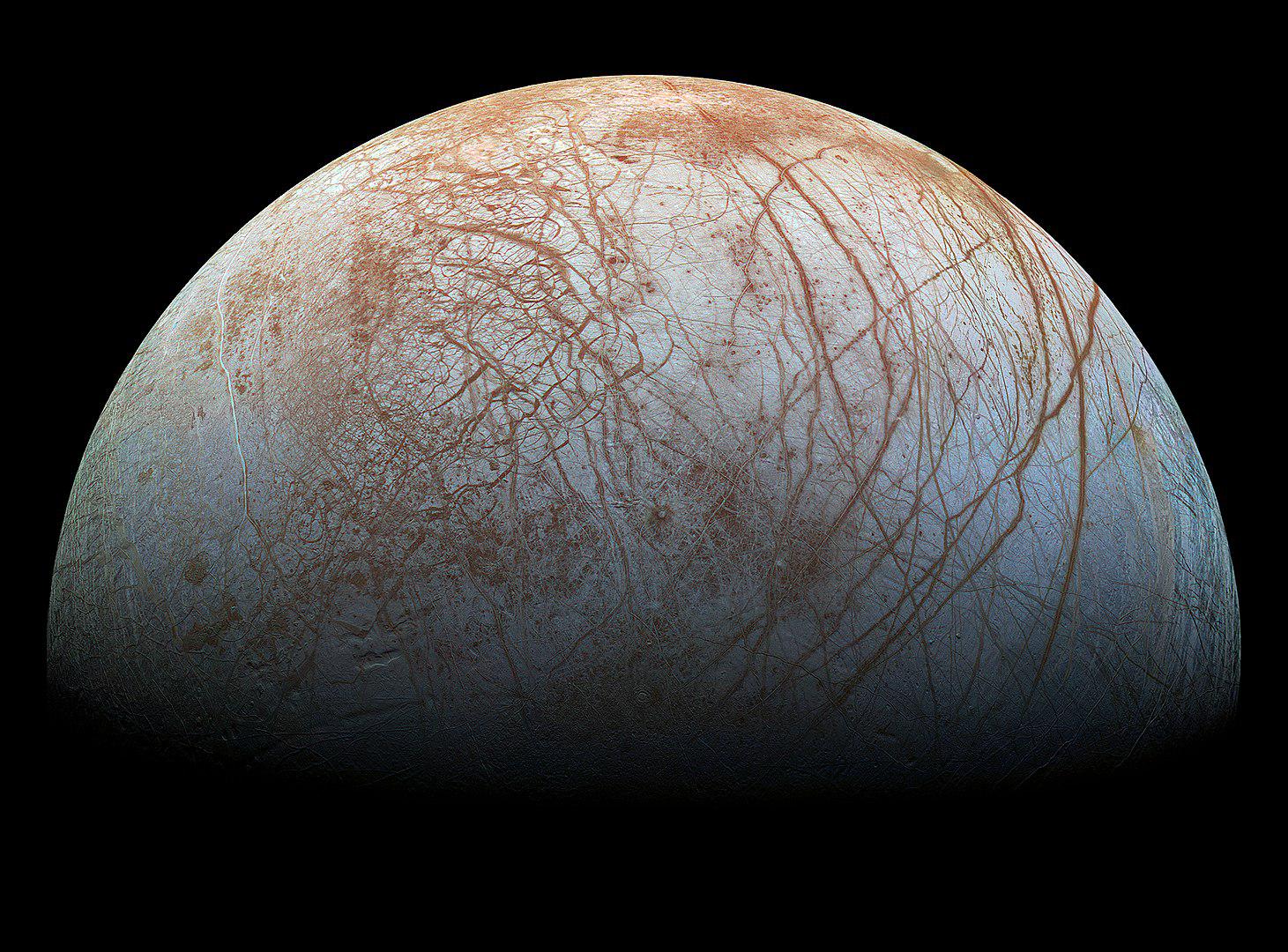

That finding may have to do with where the rock came from. “The Black Beauty meteorite is believed to come from the southern hemisphere of Mars, which does not have any young volcanic terrains. The only possible source for these young zircons is the Tharsis volcanic province located in the northern hemisphere of the planet, which contains large volcanoes that were recently active,” Martin Bizzarro adds.

That province, known as the Tharsis bulge, is a huge volcanic area that’s got the largest volcanoes, up to 21 kilometers (13 miles) high, yet seen anywhere in the solar system. It’s believed that since Mars lacks plate tectonics, volcanoes gather in a single area, beneath which a massive reservoir of magma is likely located.

First author of the study is Mafalda Costa , who says, “Having samples of the deep interior of Mars is key. This means that we can now use these zircons to probe the origin of the volatile elements on Mars, including its water, and see how it compares with Earth and other planets in the Solar System.”

The most important element the zircons contain for the purpose of looking into Mars history is hafnium. Bizzarro explains that hafnium “retains a memory of where the zircon formed. We found that the hafnium isotope composition of the young zircons is unlike any of the known Martian meteorites, which indicates that the young zircons come from a primitive reservoir that we did not know existed in the interior of Mars.”