The world must learn from “karoshi,” Japan’s overwork epidemic — before it’s too late

- Karoshi, or death from overwork, has been a recognizable social problem in Japan since the 1970s.

- A recent WHO/ILO study found that work-related deaths and disability-adjusted life-years have risen worldwide.

- Solving the karoshi problem requires us to rethink human rights and hold businesses and governments accountable to protect them.

What are the most dangerous occupational hazards? If you’re like most people, myself included, you probably answer this question by channeling your inner compliance officer. You conjure images of shaky ladders, heavy machinery, and asbestos-filled insulation. Not that you’d be wrong to do so. When present, these conditions create dangerous working environments, and in the United States.

Rarely do we consider the harm a job’s social environment can have on workers, and when we do, it’s often seen as more of a nuisance than a life-debilitating concern. We frame work-related stressors as something we have to put up with or a problem for those who can’t hack it. And we do so to our detriment. As work-related stresses grow, they can create psychosocial hazards that risk not only a person’s psychological well-being but their physical health as well.

There is perhaps no more prominent example of this than the Japanese social issue of karoshi, death from overwork. First recognized in the 1970s, karoshi has resulted in hundreds of deaths in Japan in recent years. Unfortunately, the rest of the world doesn’t seem to have learned the lesson as deaths attributable to overwork have risen worldwide.

Stress is an occupational hazard

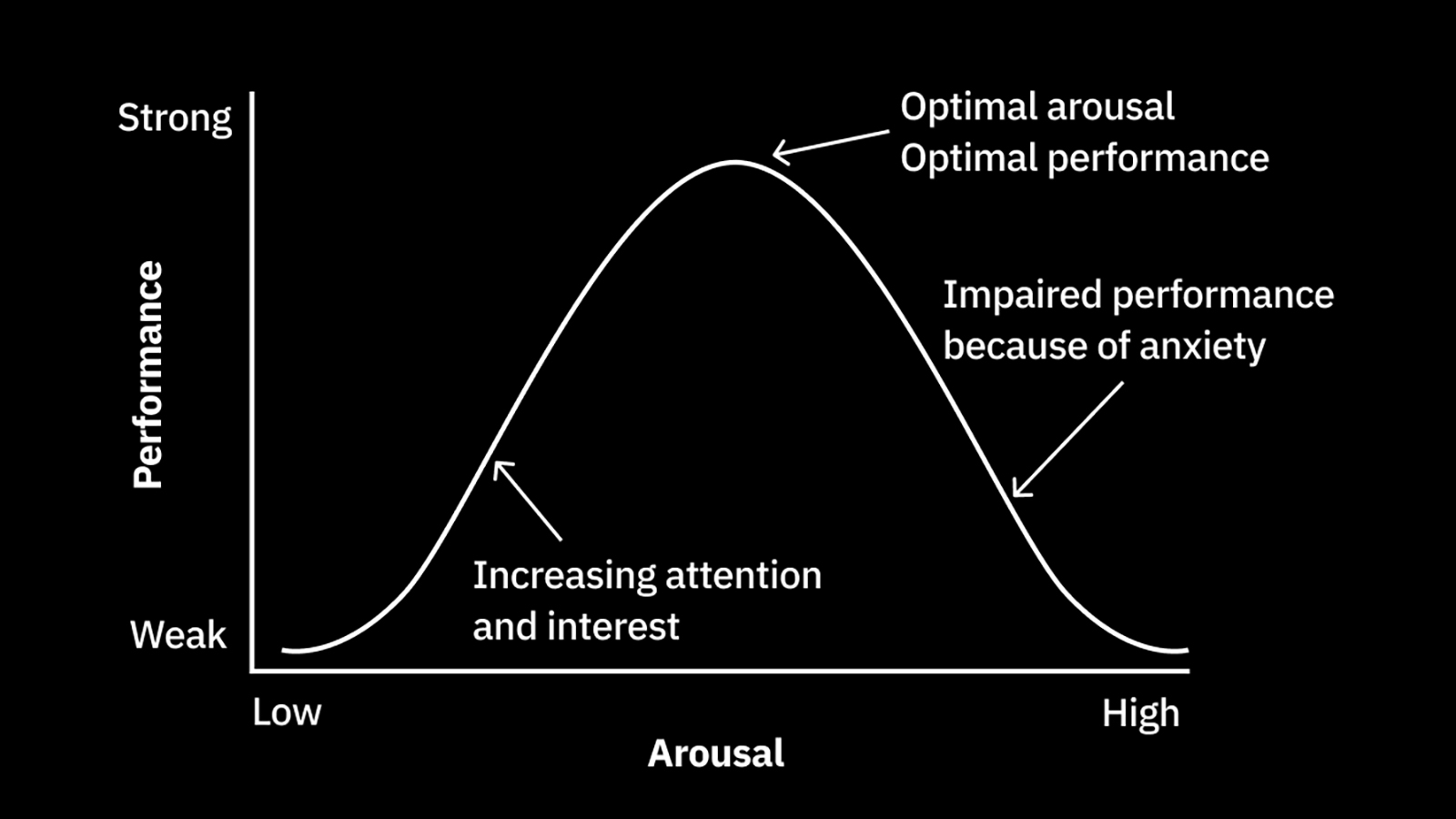

Medical professionals aren’t entirely sure how psychosocial hazards lead to death or disability. One possibility is that chronic stress causes the body to hold on to hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline for long periods. Left unabated, these hormones wear down the body’s circulatory systems, causing hypertension and leading to strokes or heart disease.

Another possibility is that chronic stress disrupts our mental health, leads us to adopt harmful habits in order to cope. These may include smoking, drinking excessively, impaired sleep, not exercising, not socializing, and so on. Over time, these habits wear down the body and increase cardiovascular risk factors. (It could be a complex interplay of the two or a third yet unrecognized trigger, too.)

Either way, a robust association between chronic stress and potentially life-threatening ailments is present in the research, and Japan’s long-overworked population offers some of the most frightful cases.

In July 2013, Miwa Sado was found dead in her apartment clutching her phone. A reporter for NHK, Japan’s national broadcaster, Sado had been covering two local Tokyo elections in the month leading up to her death. To keep up, she logged 159 hours of overtime and rarely took a day off. The strain from such a demanding workload induced congestive heart failure. She was 31 years old.

Similarly, Joey Tocnang, a 27-year-old Filipino trainee, died of heart failure in 2014 after working 122 hours of overtime at a Japanese casting company. In 2015, Matsuri Takahashi, a 24-year-old employee at a Japanese advertising agency, took her own life* after her grueling schedule left her “physically and mentally shattered.” And in 2019, a reporter in his 40s died after clocking in a five-month average of 92 hours of overtime. He worked the same beat for NHK as Sado.

These are hardly unique, isolated incidents either. According to a 2016 government survey, roughly one in five Japanese workers are a risk of karoshi.

Karoshi, a Japanese epidemic

The reasons for such grueling schedules are multifaceted. For one, the Japanese have been enduring a labor market shortage for decades.

After the collapse of the Japanese economic bubble in the 1990s and the subsequent global recession, Japanese companies aimed to reduce costs through layoffs and corporate restructuring. The workforce continued to shrink as population numbers declined and Japan’s baby boomers aged out of the workforce. (Today, Japan also has the highest senior population ratio in the world.)

The labor shortage and dwindling productivity led to intense demands and pressures being put on the workers who remained. These demands included long hours, but also intense workloads and social stressors. By 2004, as much as 12% of the population was working 60 hours or more per week.

“In Japan, people are working overtime because it’s just too much work for one person to handle,” Yohei Tsunemi, a lecturer at the Chiba University of Commerce, told The World. “What needs to happen is that we have to cut down on the volume of work that needs to be tackled and also improve the employer-employee relationship.”

Another reason is that Japanese culture values hard work and long hours preeminently. Colleagues who leave earlier aren’t seen as serious about their job and are viewed as lacking diligence and loyalty. Even sleeping in public from exhaustion — called inemuri or “sleeping while present” — can enhance your reputation at work.

This cultural mindset bleeds into managerial practices. Supervisors use hours on (and off) the clock as the yardstick of productivity and performance. As Yoko Ishikura, professor emeritus at Tokyo’s Hitotsubashi University, told Business Insider: “Many companies [and] bosses evaluate performance by face-time. They do not know how to evaluate performance other than the time.”

Of course, we don’t want to paint with too broad of a brush either. Different industries have their own cultures within the larger Japanese context, and these place unique demands and workloads on people.

Data from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare found that retail, transportation, and manufacturing saw high numbers of brain/heart disease and mental health cases between 2010 and 2015. Meanwhile, industries like agriculture and education saw low numbers of both, while healthcare saw high numbers of cases related to mental health but not disease.

From epidemic to pandemic?

Because the phenomenon was first identified in Japan, karoshi has largely been viewed — in Western countries at least — as a uniquely Japanese problem. While certain aspects of Japanese culture may foment overwork, it is hardly alone. In fact, it may have proven something of a bellwether warning.

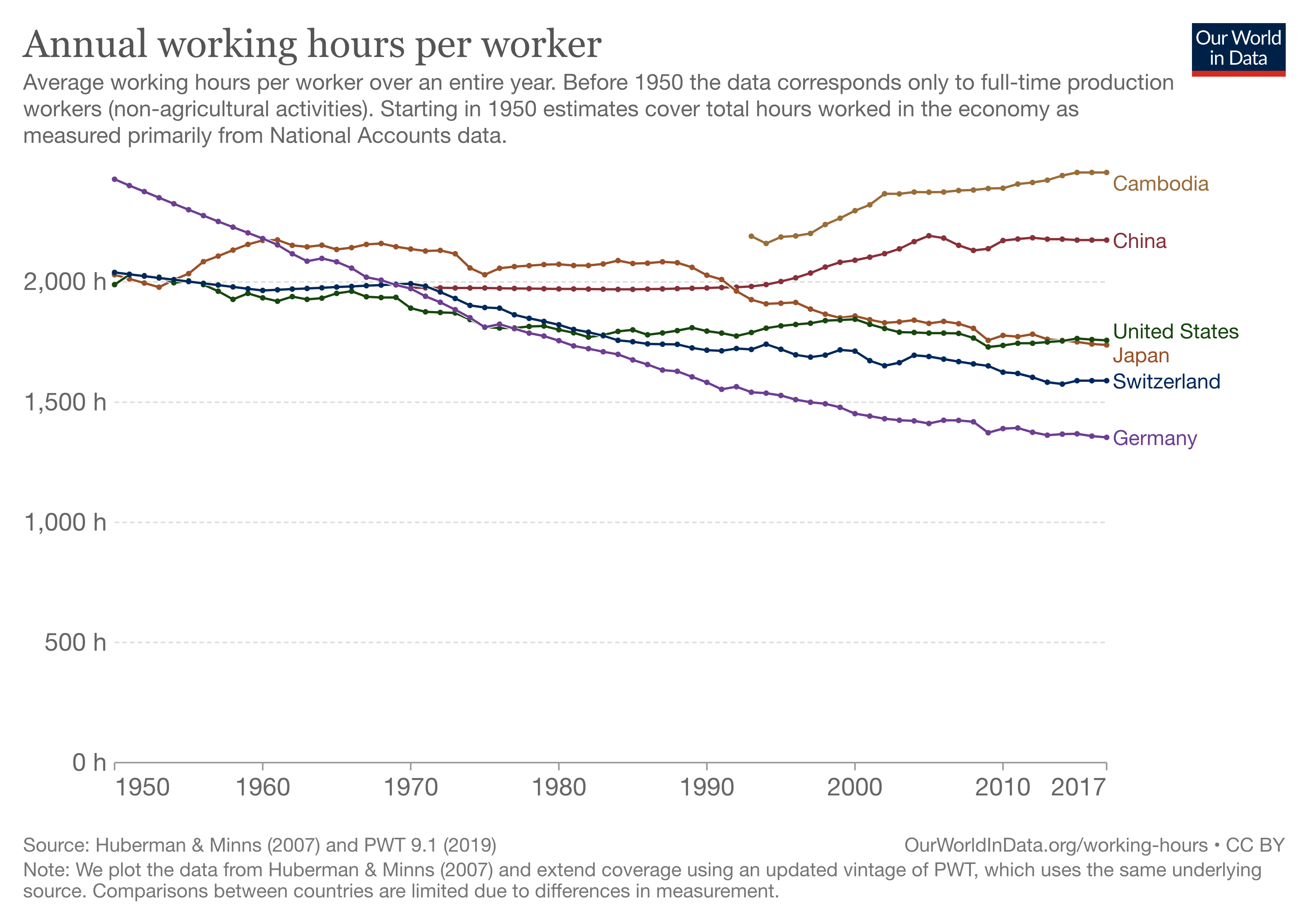

After nearly a century of work hours being reduced across the world, in many countries the trend has stopped. In some, it has begun to reverse.

A recent joint study by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) looked at the association between exposure to long work hours and subsequent risks of stroke or ischemic heart diseases. Their combined meta-analyses and systematic reviews encompassed 183 countries for the years 2000, 2010, and 2016.

According to their data, in 2016, 488 million people — or roughly 9% of the global population — were exposed to long working hours. The researchers also found sufficient evidence that such work schedules were harmful and increased the risk of stroke and heart disease.

“Working 55 hours or more per week is a serious health hazard,” Maria Neira, director of WHO’s Department of Environment, Climate Change, and Health said in a press release. “It’s time that we all, governments, employers, and employees, wake up to the fact that long working hours can lead to premature death.”

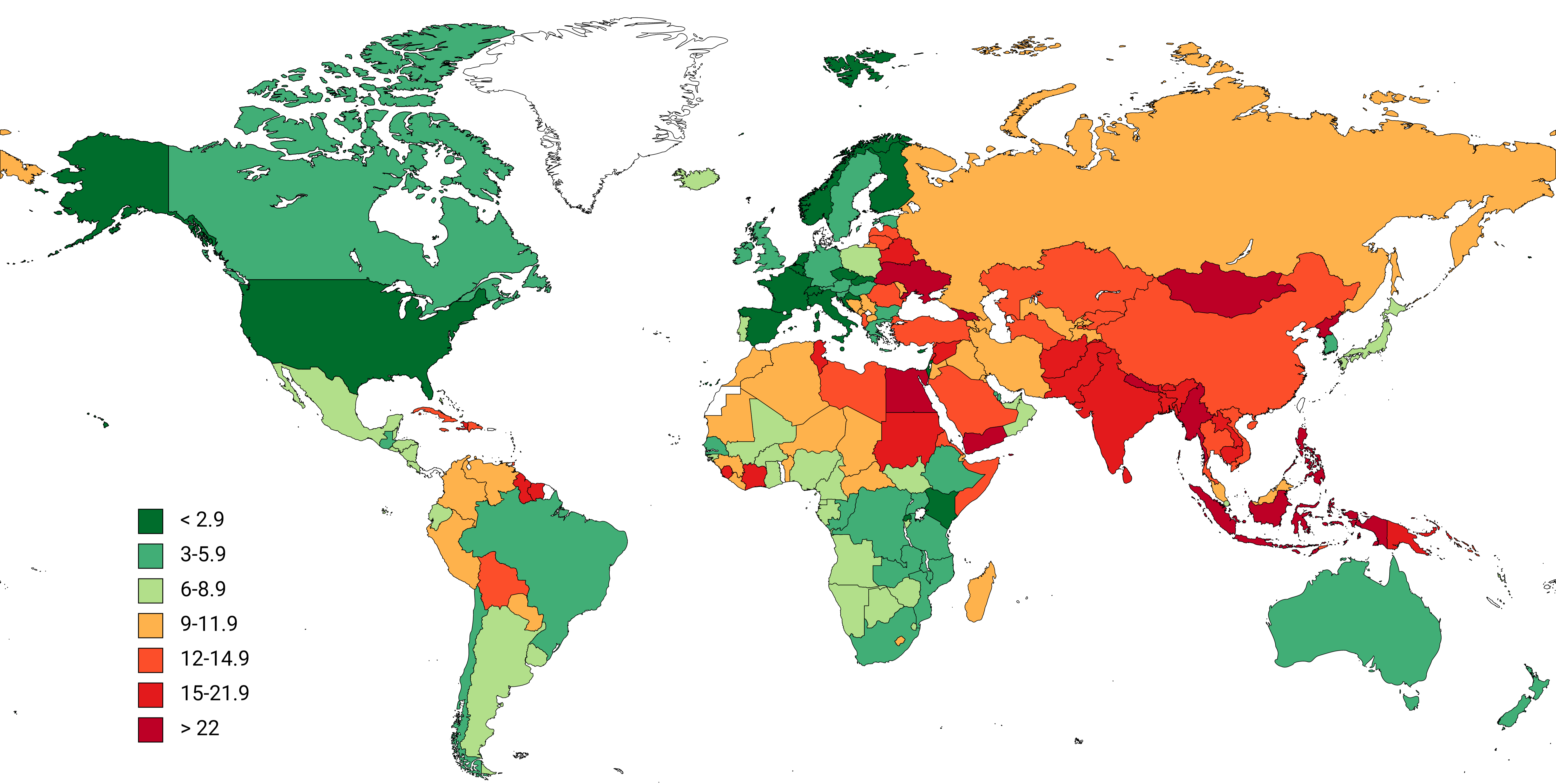

The dangers were not evenly distributed worldwide. The Western Pacific and South-East Asian regions had the largest percentage of their populations exposed to long work hours, while the European region had the least. Additionally, men and early middle-aged adults were more likely to work such schedules, and most deaths occurred among people between 60 and 79 years old who had a history of working such hours.

All told, the researchers estimated that in 2016, nearly 750,000 deaths worldwide, from stroke and heart disease combined, were attributable to long work hours — representing a 29% increase since 2000. They also warn that changes to work life since then — such as the rise of the gig economy, employment uncertainty, and new working-time arrangements brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic — may increase workers’ risk of longer hours.

“Past experience has shown that working hours increased after previous economic recessions,” the WHO/ILO researchers write. “If this trend continues, it is likely that the population exposed to this occupational risk factor will expand further.”

The struggle to solve karoshi

In the face of lawsuits and intense public pressure, the Japanese government has attempted to curb the country’s karoshi epidemic, but its efforts have proven mixed.

In recent years, it instituted a “Premium Friday” program giving employees half a day off on the last Friday of every month. The idea was to promote work-life balance while also bolstering the economy. But the stunt lacked enforcement beyond a cringy advertising campaign and became, in one reporter’s words, “a laughing stock.”

The government also began publishing a list of so-called “black companies” that flouted labor laws. As reported by Reuters, the hope was to “name-and-shame” companies into compliance. But it too failed to move the dial.

In 2018, then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe worked with legislators to pass the “Work Style Reform Law.” In general, the law limits overtime work to 45 hours per month and caps overtime at 350 hours annually. It also mandates stricter annual leave requirements.

“While I think the situation is better, the actual situation has not yet been clearly improved even with the overtime law becoming much stricter in Japan,” attorney Erika Collins told the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). “Many Japanese people still think that long hours of work [are] valuable and that long hours … show employees’ industriousness.”

However, the law has some provisions that reformers argue create loopholes for malfeasance. These include relaxing overtime limits during busy seasons up to 100 hours per month — an amount well above the 55 hours the WHO labels as dangerous. It also excluded “highly skilled professionals” from such protections.

To date, the law does seem to have reduced the monthly average working hours in the country, as reported by the SHRM. However, the same report notes that in a government survey, 37% of companies inspected from 2020 to 2021 still exceeded overtime limits (roughly 9,000 workplaces).

And in 2019, the same year many of the reform law’s provisions took effect, the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare announced nearly 3,000 karoshi-related claims. Roughly 1,000 cases were related to brain and heart diseases, with another 2,000 cases attributed to mental health disorders. The figures represented an increase of nearly 300 claims from the previous year.

What can be done to ease karoshi?

It’s worth noting that the WHO/ILO study focused on long work hours because this psychosocial hazard represents “the risk factor with the largest occupational disease burden.” But it’s hardly alone.

At the intersection between health, individual lives, and social conditions lie many potential psychosocial hazards. They include a lack of control at work, highly demanding work, overly monotonous tasks, employment insecurity, interpersonal conflicts, and inadequate rewards. As these hazards combine and compound, they create health hazards far greater than any one in isolation.

In short, it isn’t just the hours worked that matter. The quality of the work and the social environment are vital to consider as well. But as we’ve seen with recent calls for labor strikes or irresponsible CEO’s demanding their workforce level up to “extremely hardcore,” that quality is degrading across many industries.

“We have widespread karoshi. We simply don’t call it that,” Peter Schnal, an epidemiologist and co-director of the Healthy Work Campaign, told Slate. “The stressors that are created by modern work are basically ignored in our society, and therefore most people are not aware of what the impact of work is on their health.”

Any course correction would require major changes in how many countries view workers’ rights and occupational safety. As Japan’s recent struggles show, that’s an incredibly difficult task that requires major changes in the mindset of governments, large corporations, small businesses, and individual workers.

It’s made extra challenging by the lack of a one-size-fits-all solution that can be rolled out worldwide. Wealthy and technologically advanced countries, for example, will have an easier time maintaining, or even increasing productivity, while simultaneously reducing work hours than poorer countries. Countries like Germany and Switzerland bear this out. Both have some of the lowest work hours on record yet also some of the highest productivity.

Moving forward, businesses must be more proactive in changing workplace culture and expectations. Senior leaders and managers must decouple the false belief that face-time and productivity are synonymous. In fact, research suggests that productivity drops after reaching certain thresholds. Focused, quality work should be the evaluation of performance — not butts in seats. Businesses must also better recognize the workplace as a holistic part of employee lives and cultivate it as such.

“We really want employers and organizations to understand that this is not just an individual problem. Work stress impacts their bottom line because it’s impacting employee health and productivity. People who leave their jobs cost employers money because they have to replace those people. Also, health care costs and disability leave, employers are paying those costs,” Marine Dodson, epidemiologist and fellow co-director of the Healthy Work campaign, told Slate in the same interview.

Governments should recognize psychosocial hazards as part of their national occupational health and safety — which very few do. Once recognized, they need to create and enforce laws to prevent such harm as they would for any other occupational hazard. And the punishments for breaching such laws must be more severe than a short-lived public shaming or a slap-on-the-wrist gesture.

Finally, workers need to recognize the signs of overwork rather than assuming stress or exhaustion to be a character flaw. When possible, they should take personal measures to relieve themselves of that stress. Those may include focusing on relationships, engaging with hobbies, simplifying life where they can, taking mental health days, and using all of their vacation time.

If the stress leads to health concerns, physical or mental, they should seek professional help as soon as possible. If the concern is immediate, they can reach out to local or national organizations such as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or SAMHSA’s National Helpline for help.

Whatever our role, we could all do better to recognize the harm psychosocial hazards can have at work. By destigmatizing the psychological challenges of work and the need for support, we make our organizations and cultures better, healthier places for everyone to make a living and live their lives.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.