Salman Rushdie was nearly “cancelled” by free speech advocates

- Long before Salman Rushdie was embraced by free speech advocates, he was spurned by both sides of the political spectrum for being “offensive.”

- Fearing for his life, Rushdie had to go into hiding, and some critics suggested that he only had himself to blame.

- Offensive, obnoxious free speech is vital to democracy. Perhaps tolerance of it will lead to much needed reform in the Middle East.

Salman Rushdie has reemerged following an assassination attempt in August of this year. The attack left him blinded in one eye and without the use of one of his hands.

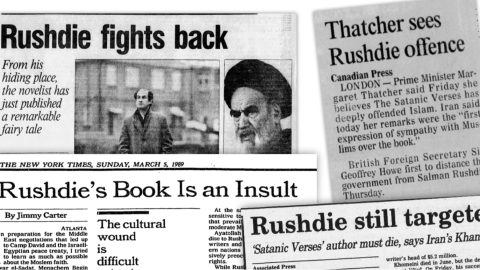

Free speech advocates around the world rallied to his cause. But this wasn’t always the case. In fact, many people (from both sides of the political spectrum) tried to “cancel” Rushdie before that term was invented.

A (rushed) history of Rushdie

Salman Rushdie published his book The Satantic Verses in 1988. Unfortunately for him, his book was about to take center stage as a political football, used by a number of groups claiming to be the most ardent defenders of the Islamic faith. In particular, Rushdie’s caricature of Ruhollah Khomeini, which may have been one of the only parts of the novel that the Iranian leader actually read, insulted the Ayatollah. Rushdie indicated that he didn’t see the global backlash coming when he later said, “I expected a few mullahs would be offended, call me names, and then I could defend myself in public.”

According to The Guardian:

“Noticing the protests in India and Britain, a delegation of mullahs from the holy city of Qum read a section of the book to Khomeini, including the part featuring a mad imam in exile, which was an obvious caricature of Khomeini. As one British diplomat in Iran said: ‘It was designed to send the old boy incandescent.’”

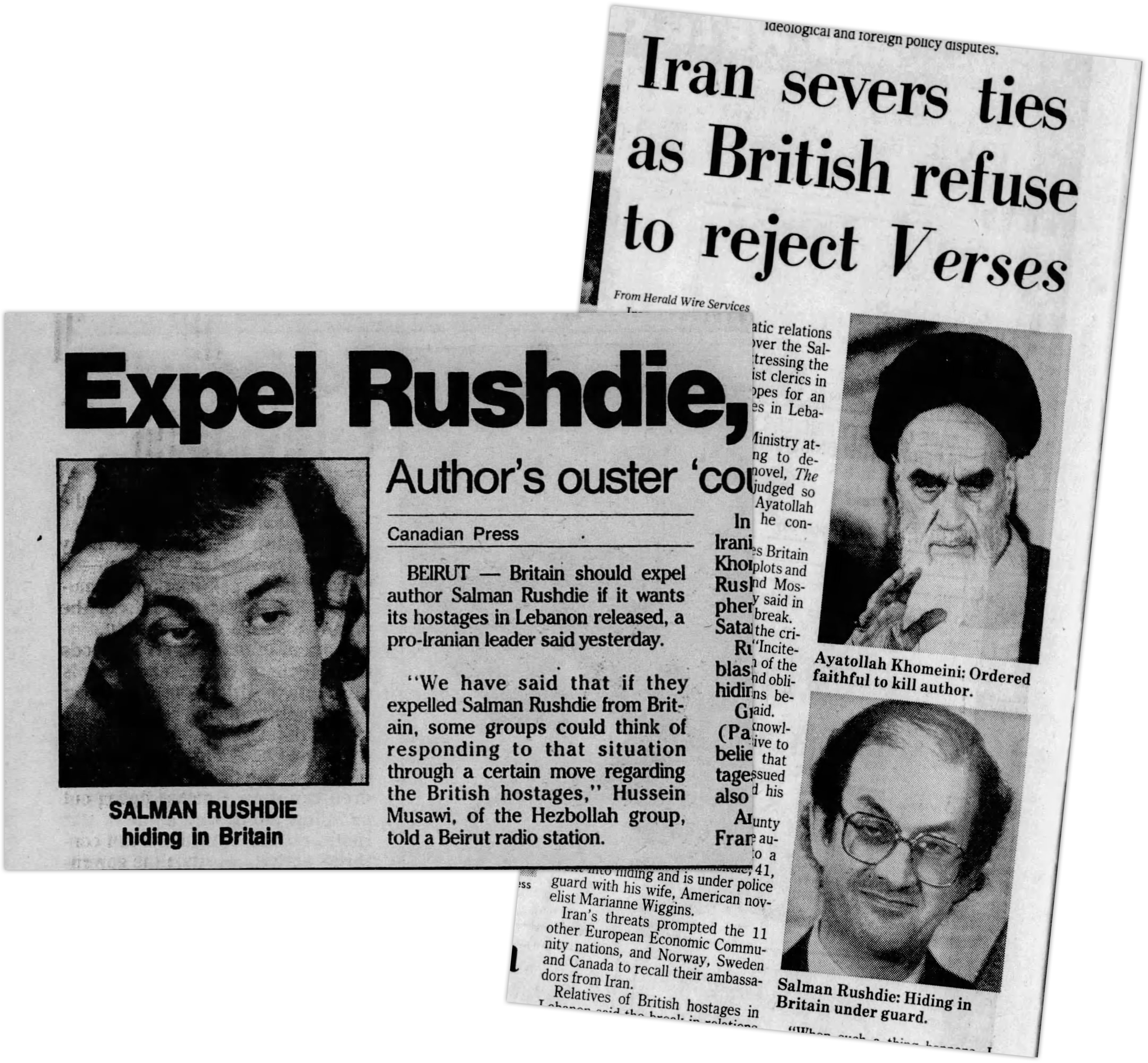

Rushdie was forced to go into hiding, using an alias and living on a farmhouse in Wales for nine years. Yet many of the people that you might have expected to defend Rushdie were absent from the debate, and some even suggested that he was responsible for his own persecution.

Blame the victim

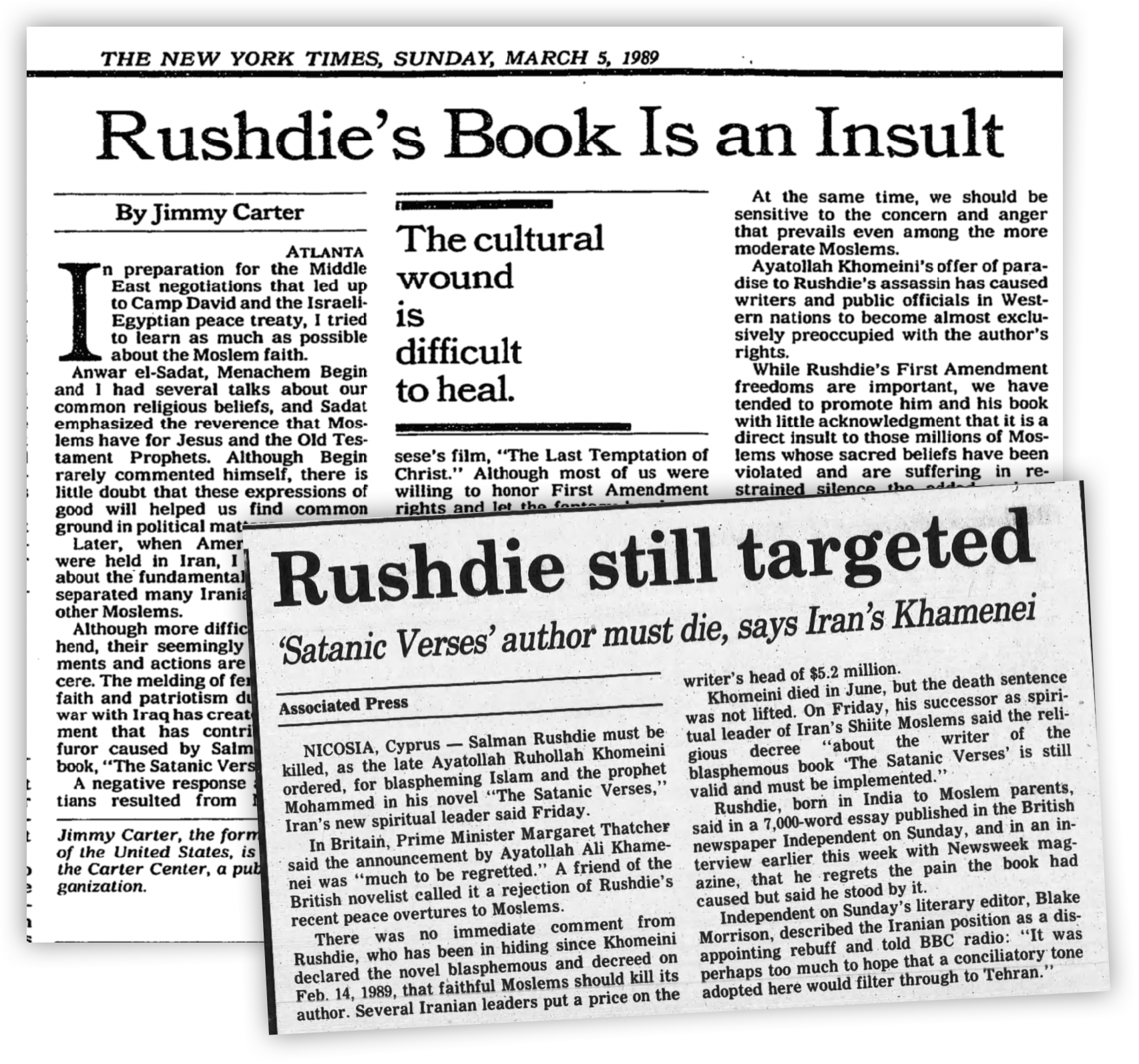

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter wrote an article in the New York Times called “Rushdie’s book is an insult,” in which he suggested that his own religious faith made him sympathize more with the offense taken by Islamic groups (which he said was “sincere”) than with Rushdie himself.

Carter wrote that “while Rushdie’s First Amendment freedoms are important, we have tended to promote him and his book with little acknowledgment that it is a direct insult to those millions of Moslems whose sacred beliefs have been violated and are suffering in restrained silence the added embarrassment of the Ayatollah’s irresponsibility.”

Author John le Carré had a 15-year-long war of words with Rushdie after the publication of The Satanic Verses, saying, “My position was that there is no law in life or nature that says great religions may be insulted with impunity.” He added that Rushdie “perhaps inadvertently, provoked his own misfortune.”

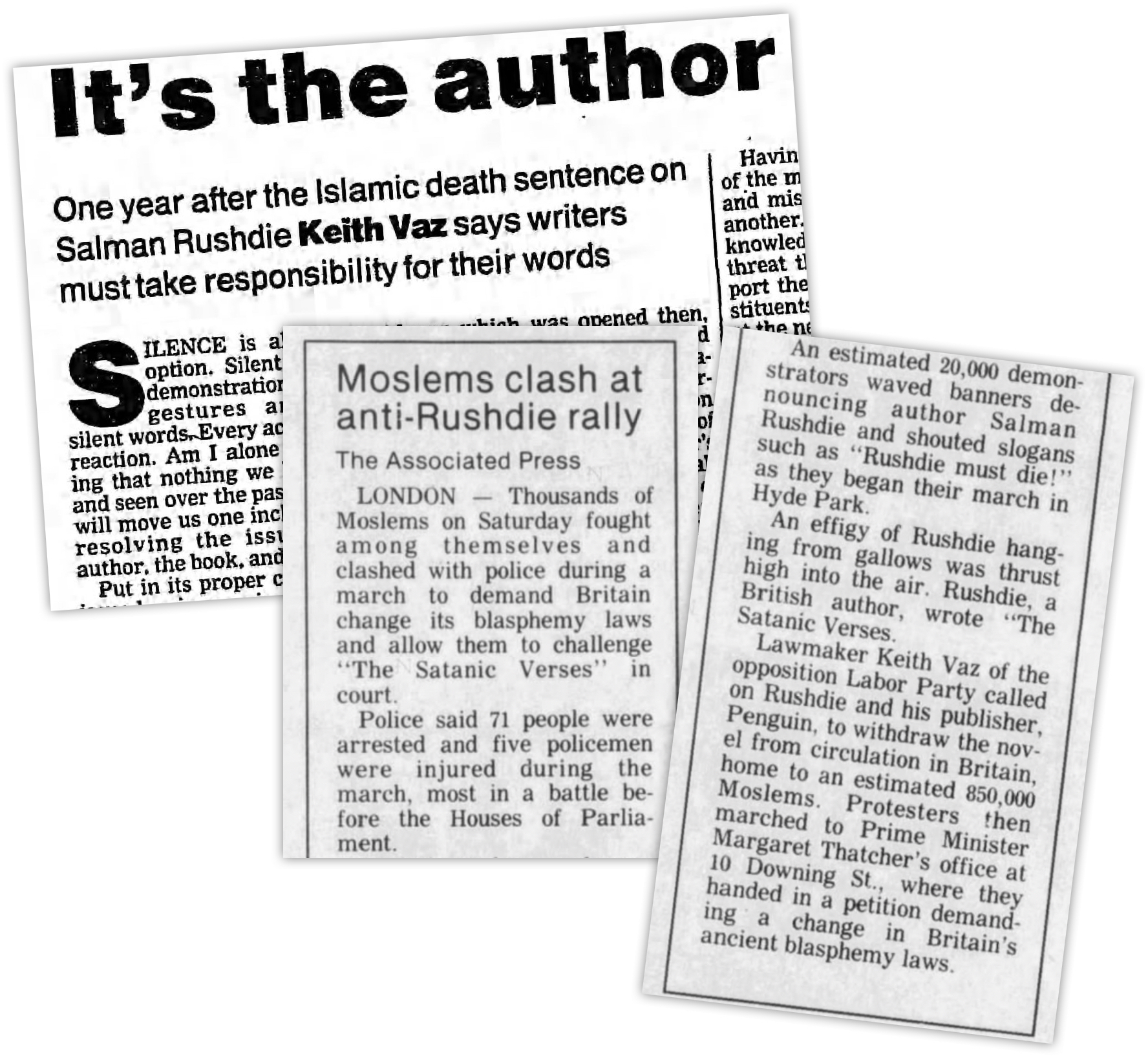

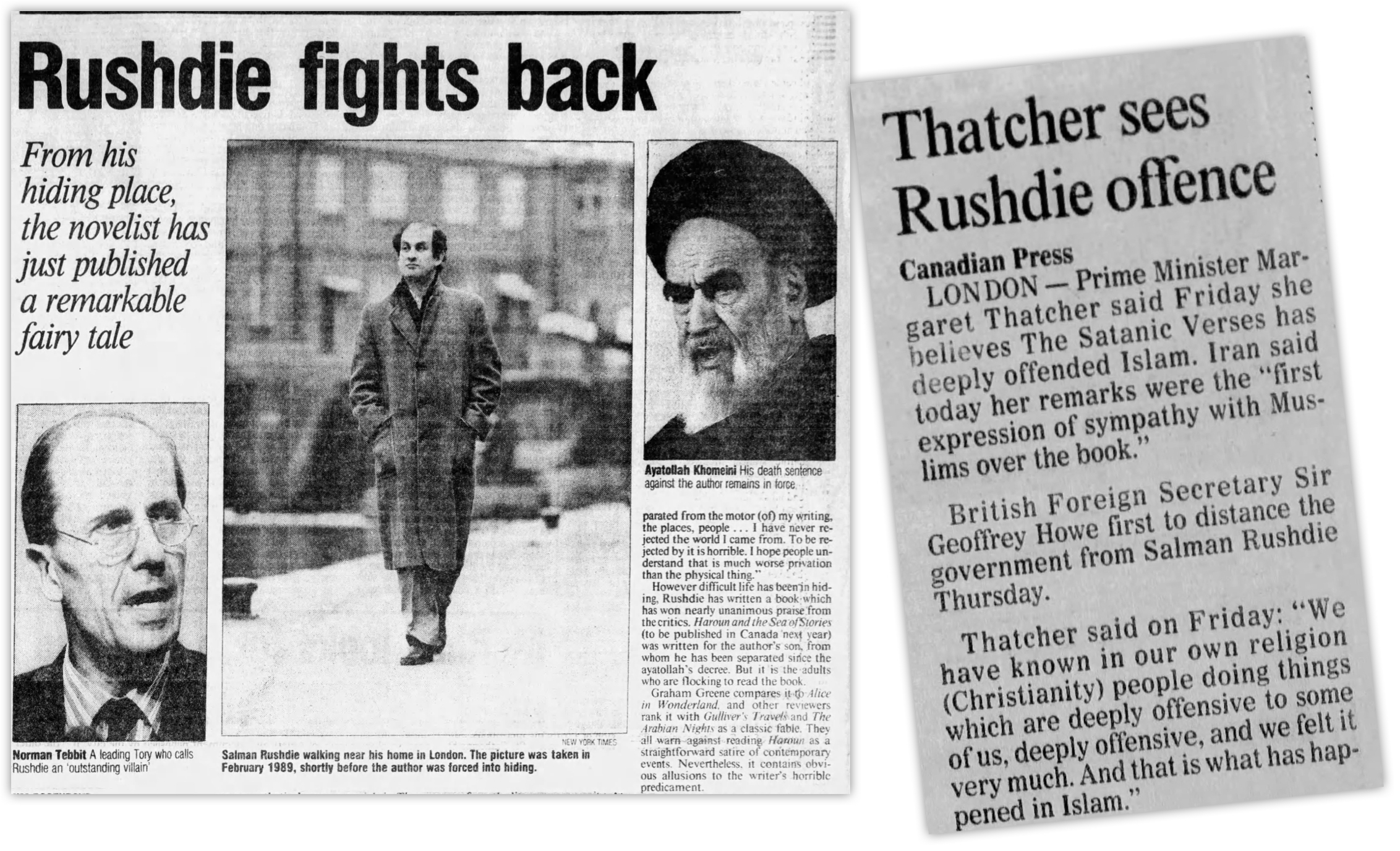

A number of British politicians also criticized Rushdie. Labour MP Keith Vaz led a march through Leicester in 1989 calling for the book to be banned, and Conservative MP Norman Tebbit called Rushdie an “outstanding villain” whose “public life has been a record of despicable acts of betrayal of his upbringing, religion, adopted home, and nationality.”

By all accounts, Rushdie’s parents were not practicing Muslims, yet even Tebbit seemed to side with a strict interpretation of Islam in which Rushdie, by criticizing Islam, became some kind of apostate. “How many societies having been so treated by a foreigner accepted in their midst, could go so far to protect him from the consequences of his egotistical and self-opinionated attack on the religion into which he was born?” Tebbit opined.

Alex Massie, writing for The Spectator in 2012, points out that Tebbit was not the only Tory to blame Rushdie for the fatwa against him. Margaret Thatcher said, “We have known in our own religion people doing things which are deeply offensive to some of us. We feel it very much. And that is what is happening to Islam.”

Geoffrey Howe, meanwhile, was as offended by the book as the Ayatollah, but for a different reason: “The British government, the British people have no affection for this book… It compares Britain with Hitler’s Germany… We do not like that any more than people of the Muslim faith like the attacks on their faith.”

Massie points out that Howe obviously didn’t read the book, because it doesn’t actually compare Britain to Nazi Germany. Thatcher may have been lukewarm to Rushdie for personal reasons, including that he had called one character in The Satanic Verses “Margaret Torture” and frequently criticized British imperialism. (She did however rebuff calls from Iran to ban the book, and after she died, Rushdie expressed gratitude that she had ordered security services to protect him.)

Faux outrage

Worse, there is reason to believe that the global outrage was manufactured. While Khomeini was personally offended by his portrayal in the book, there are reasons to believe that Iran was not particularly sincere in its fatwa against Rushdie and was simply using it for clout-chasing. The Iran-Iraq war had just come to an end, the USSR was pulling out of Afghanistan, and Iran was looking for ways to distract people from domestic dissent — essentially, to show that it (and not Saudi Arabia) was the true leader of the Muslim world.

In the UK, the Saudis were funding the United Kingdom Action Committee on Islamic Affairs, which organized protests against Rushdie. According to The Guardian, “It featured Islamists like Iqbal Sacranie, the future head of the Muslim Council of Britain. (Sacranie famously opined that ‘death, perhaps, is a bit too easy’ for Rushdie. He was later knighted for services to community relations.)”

Like Keith Vaz, other Labour MPs with sizeable Muslim populations in their constituencies felt it was not a good look for them to defend Rushdie in public. When Rushdie was knighted in 2007, Liberal Democrat MP for Rochdale, Paul Rowen, asked Labour’s Jack Straw to explain why Rushdie was knighted, saying “I am sure that like Rochdale, Mr Straw has had a number of complaints from Constituents who are furious at this award.” Straw replied that he understood “the concerns and sensitivity in the community.”

A convenient bogeyman

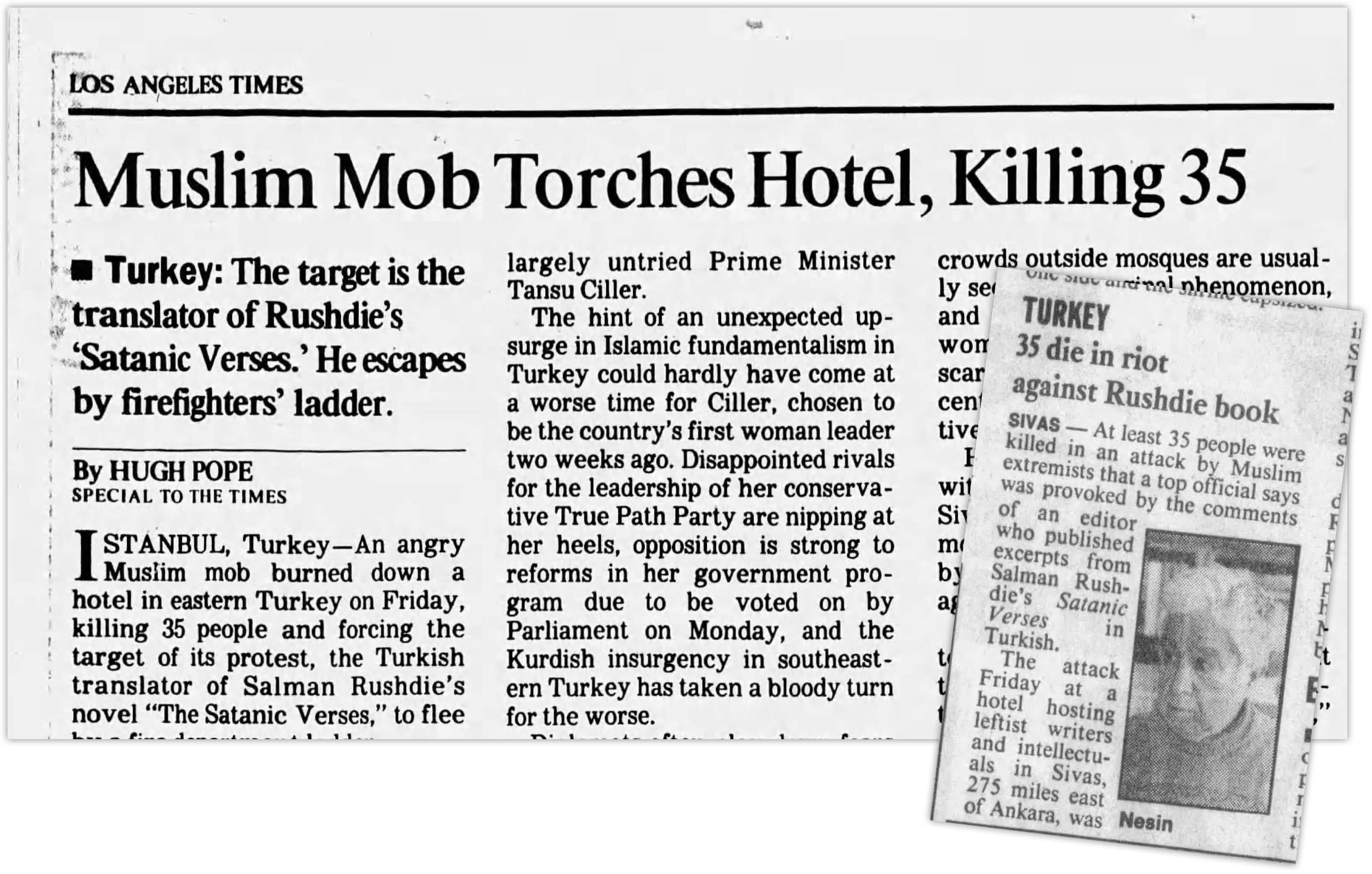

Rushdie has been demonized and used as an excuse in the political machinations of a number of leaders both in the West and Middle East. The 1993 Sivas massacre in Turkey, in which 37 people from the country’s minority Alevi group were killed after their conference was attacked by hardline Sunnis, was blamed on the fact that someone in attendance had tried to publish The Satanic Verses in Turkey. In reality, pogroms against Alevis in Turkey have occurred on and off for centuries.

As Amir Taheri argued in the Index on Censorship in 1989, the biggest persecutor of Muslims was Khomeini himself, with up to 1.8 million killed during the war with Iraq. He was a man prepared to crush millions of fellow Muslims under the wheels of his own political ambitions.

The moral of the story

It seems that we have to keep re-learning the same lesson over and over again — namely, that free speech, even of the offensive, obnoxious variety, is vital to democracy. And just as the challenge to a literalist interpretation of the Bible in the West has led to more tolerant, pluralistic societies, challenges to a literalist interpretation of the Qur’an could open the door to political and social reform in the Middle East.