77 – The Abercrombie Plan for London as a Park City

n

No cloud without a silver lining: the extensive bombing damage to London during the Second World War provided an opportunity to develop a drastic plan for a green, open-spaced city in the post-war era. Even before the bombing began, London already had a reputation as being an open-spaced place, albeit in an unplanned fashion, having engulfed royal parks such as St James’s, Green and Hyde Parks in a 19th century growing spurt. This impromptu arrangement inspired planners such as Haussmann, who applied its principles to the redesign of Paris, and Frederick Law Olmsted who had it in mind while creating the Emerald Necklace in Boston.

n

Town planner Leslie Patrick Abercrombie devised the County of London Park System in 1943 and the Greater London Regional Plan in 1944, while the bombs were still falling. The second plan being an elaboration of the first, both are known collectively as the ‘Open Space System’ or simply the ‘Abercrombie Plan’, because both clearly bore the stamp of his half century of experience in architecture and planning. Abercrombie (1879-1957) had been professor of Civic Design at the Liverpool School of Architecture and of Town Planning at University College in London. He was past president of the Town Planning Institute, a member of the Institute of Landscape Architects and a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Pre-war, he made award-winning designs for Dublin, Hull, Bath, Edinburgh, Bournemouth and other cities. After 1945 (when he became a Sir), Abercrombie was commissioned to redesign Hong Kong by the British government, and by Haile Selassie to draw up plans for Addis Abeba.

n

“Adequate open space for both recreation and rest is a vital factor in maintaining and improving the health of the people”, begins the ‘Abercrombie Plan’. It’s at once a visionary plan, in that it creates a coordinated Park System, and a very detailed one in its many comments and varied recommendations.

n

Details such as the contemporary ratio of open space per 1.000 persons (2,43 hectares in Woolwich, 0,04 in Shoreditch). Abercrombie proposed a ‘standard of open space’ of 1,62 hectares (or four acres) per 1.000 people, “considerably below the 2,83 hectares (or 7 acres) suggested by many competent authorities, both in this and other countries but it is put forward in view of the already highly developed use of the land in these areas.” Of these open spaces, Abercrombie said that “(they) need to be considered as a whole, and to be co-ordinated into a closely-linked park system, with parkways along existing and new roads forming the links between larger parks.” The goal was that city-dwellers could “get from their doorstep to open country through an easy flow of open space from garden to park, from park to parkway, from parkway to green wedge and from green wedge to Green Belt.”

n

Abercrombie identified seven categories of parkways: linear strips of open space; riverside walks; footpaths through farmland; bridle tracks and green lanes; bicycle tracks; motor parkways; and express arterial roads. In the plan, a Green Belt Ring of about 8 kilometres deep would be used for recreational purposes, with a mainly agricultural Outer Country Ring. In both rings, no new building would be allowed and an extensive system of radial and connecting footpaths was to be created.

n

Most of Abercrombie’s plan was never implemented in its totality; some parts were, though. The most developed part is the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority, created by a special Act of Parliament in 1968 and today still funded by a tax on all of London – apparently despite the fact that the park is mainly used by locals. Another element in the Abercrombie Plan that made it off the drawing board were New Towns to be built outside the Outer Country Ring, such as Stevenage, Harlow, Crawley and Harold Hill.

n

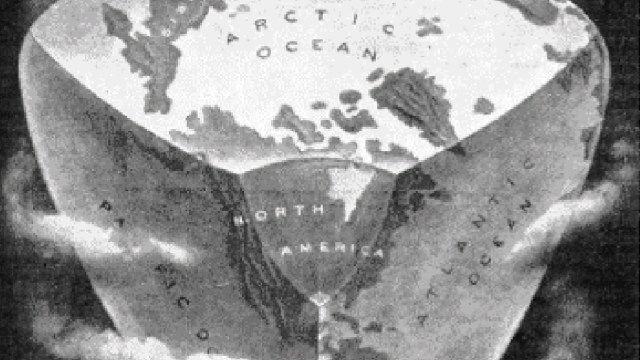

This map taken from this page at the London Landscape Web, which advocates a change in London city planning much in the spirit of the Abercrombie Plan.

n