Want to be more authentic? Don’t be like Sartre’s café waiter

- We have all interacted with someone whose actions or speech seems forced, awkward, or unnatural — as if their behavior misaligns with their true self.

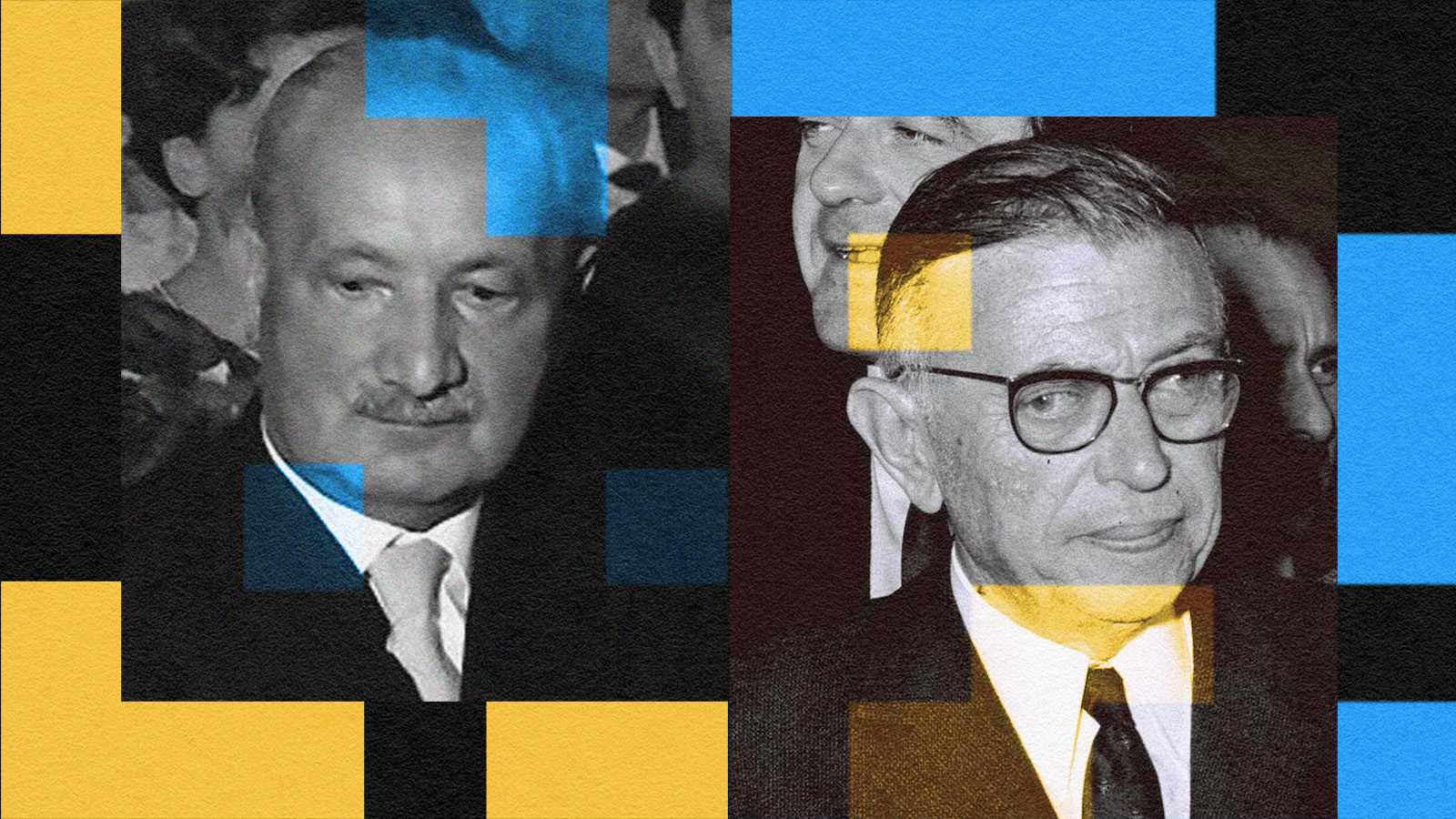

- The philosopher Jean Paul Sartre explored such “bad faith” behavior through stories about a café waiter and a woman on a date.

- Sartre defines bad faith as any moment in our life when we deny our own complicity in a situation, or when we ignore the choices available to us all the time.

It is not hard to tell when someone is being insincere. It might be that his smile doesn’t quite touch his eyes. Her apology might be belied by the ghost of a wry smile. Or the condolences someone offers are clichéd and shallow — the trite words of a $1 greeting card. But insincerity can run deeper than these everyday moments.

Sometimes when you meet someone, it can feel as if their entire being is some kind of act. It could be that their movements don’t seem entirely natural to them. It could be the clothes they wear don’t match their tone and manner. Or it could be the way they talk seems awkward, as if they’re trying to say the right thing. These are the moments when our gut tells us that the person we’re talking to isn’t being themselves, but rather acting as something or someone else.

This feeling is captured brilliantly by the French philosopher Jean Paul Sartre’s idea of “bad faith.”

Being and Nothingness

In his monumental work, Being and Nothingness, Sartre asks us to imagine ourselves in a café watching a waiter go about his business. The man is serving, bustling about, and displaying all the affectations you might expect from a Parisian waiter. But something is not quite right. His movements seemed forced, “a little too precise, a little too rapid.” He flirts and charms as a good waiter should, but “a little too eagerly…a little too solicitous.” Many would feel that something is off about the waiter, but it might not easy to articulate.

What’s going on? Sartre wrote: “We need not watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter in a café.” The man does not do his job as he would like or in a way that suits his nature, but in a way that he thinks people want him to do it. He is effectively reading a script or moving to a choreographed dance, and however perfectly he says his lines and makes his step, we recognize that they are not his own.

The waiter is everywhere. Every job or role has its demands and obligations. Any profession “is wholly one of ceremony.” The businessman must wear a suit and greet his clients with a firm handshake. The grocer must hawk their wares with the gusto of a caricature. The teacher must discipline their students and enforce the rules. Each has their lines to read. Each has expectations to meet. As Shakespeare’s As You Like It notes: “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

Living through stories

The perniciousness of the waiter story, and the ceremony of our daily lives, is that it extinguishes that element of ourselves which defines who we are. In surrendering our actions and words to the preordained script of a label, we surrender also our own authentic self. We reduce our being from a choosing, willing, and active subject of the world into a passive puppet yanked this way and that.

It can feel as if we are detached from our body, floating beyond or outside the self as it behaves and talks in a way we can’t understand. Anyone who’s acted a role for long enough can tell you that there’s a peculiar moment when it feels as if your person becomes split. There is your authentic and true self, the bit looking out at the world, and there’s the mannequin movements of your body. It is felt in all those moments you think “why did I do that?” or “I didn’t really mean that.”

Sartre provides us with another example. Imagine there’s a woman on a date for the first time with some new man. The woman is attractive and she’s aware of the fact. She knows all too well that the man would like to take her back home, and that he has less than noble intentions for this date. And yet, she does not let this play out in her head. She chooses to live instead by a narrative she has constructed — a Prince Charming and gallant date, perhaps. When the man says that he finds her very attractive, she disarms this phrase of its sexual background. She turns the suggestive comments and predatory leers into ones of “admiration, esteem, respect.” She lives by a story, and not the reality she knows is there.

Sartre notes that “during this time the divorce of the body from the soul is accomplished.” The woman lives in her head, watching her body as a “passive object to which events can happen.” The authentic self, the true person of the woman, has stepped into the auditorium and is watching her body live out the date, as if on a stage.

Bad faith

These moments, when we live not by our own choices but by the narratives prefabricated for us, are what Sartre calls bad faith. Bad faith refers to when we hide from ourselves the agency we have over our situation. The waiter refuses to see the act he is playing, and the woman on a date refuses to see the truth she knows is there. They hide their complicity in their circumstances or the choices they’ve made and will make. It’s important to note that the woman who on no level suspects her date of being lascivious is not guilty of bad faith (only of naivety, perhaps).

Sartre’s bad faith is one of his most relatable ideas. Anyone who takes great relish in throwing off their “work clothes” when they get home knows what he means. Anyone who gets tired and frustrated at wearing painted smiles and rehashing trite greetings knows what he means. Anyone who has given into the pressure of a million people to behave a certain way knows what he means.

We all live vast swathes of our lives in bad faith. Giving it a name, and calling it out, might just allow us to make things a bit better. But as Sartre would be the first to point out — only if you want to.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.