How not to be a phony: Kierkegaard on the two main ways people lose their true selves

- According to Soren Kierkegaard, we are each pulled in two directions: toward the “finite” or the “infinite.”

- When we lean too far in either direction, we risk living stagnant and inauthentic lives.

- To be a human is to accept that we are both finite and infinite. We must walk the middle bridge that lies between the two chasms that risk consuming who we are.

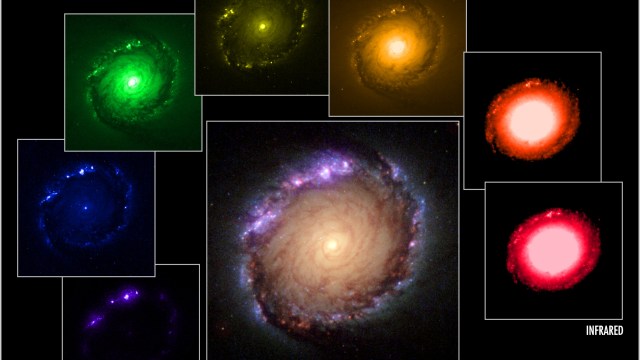

In terms of making meaningful and authentic decisions, we are a species walking a narrow bridge with two chasms framing our way: the finite and the infinite. On the finite side lie the fixed conditions of everything we are. These are the facts of our existence that force us to live in certain ways: the needs of our body, the wiring of our brain, and the pull and push of necessity. On the infinite side lies a universe of potential — all the things we think we might someday do or become, a future full of possibilities with no set course laid out.

Both sides have their sirens’ calls that beckon us with promises of comfort, and both risk rendering us unable to move forward authentically in our lives. For the Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, the wise but hard task of life is to walk the path between these two abysses: to be neither finite nor infinite but find the middle way.

Becoming a cipher

Right now, you have innumerable desires, cravings, worries, phobias, or dreams tugging you this way and that. For most of your life, you’ll give in to them. You’ll scratch an itch, drink some water, smile at a good-looking girl, go to bed, nurse a wasp sting, and so on. In these moments, you live in the finitude of your existence — the reality and necessity of life.

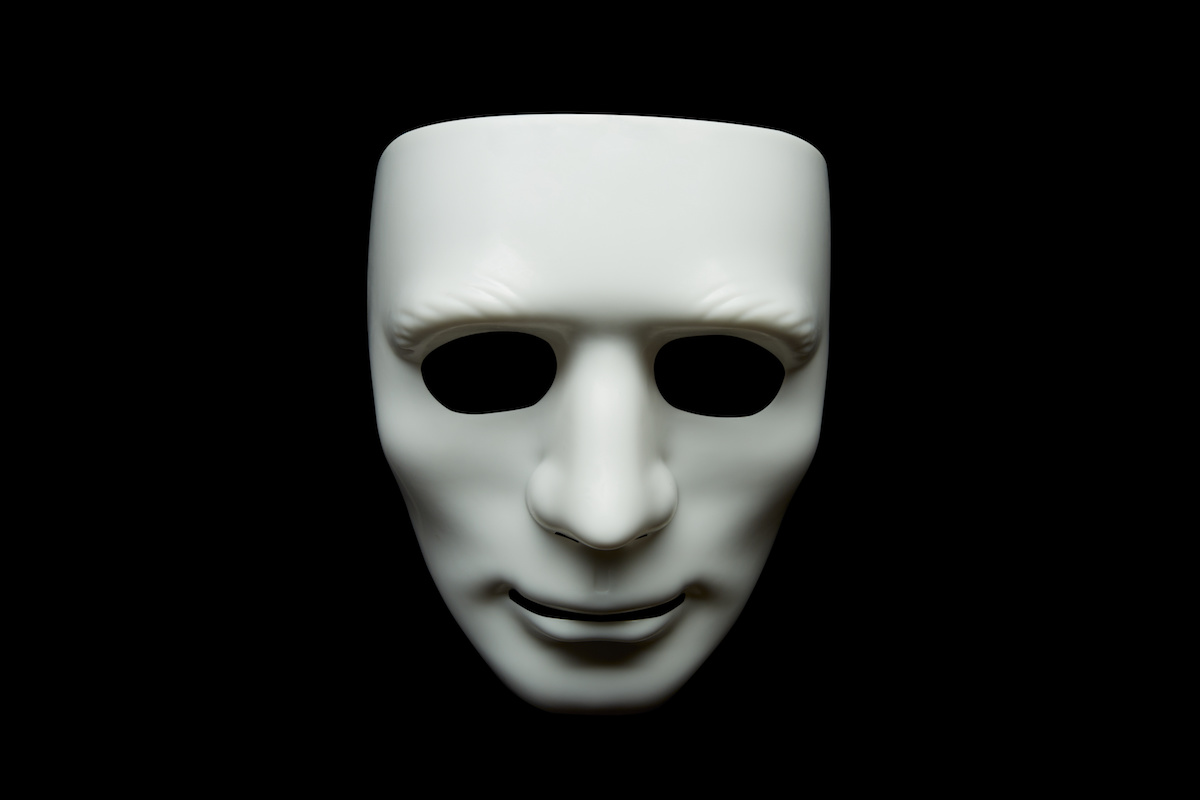

For many people, this is all there is: a world that Kierkegaard calls “aesthetic.” The problem is that if we live only for our needs and whims, then life will rattle by without anything bigger. When we live only for the aesthetic, and embrace too fully the finite alone, we risk losing ourselves. We can do this in two ways. One is to become a slave to our desires — a kind of hedonistic automaton. Another is to become a faceless, uninteresting drone among the masses — or, as Kierkegaard put it, “like the others, to become an imitation, a number, a cipher in the crowd.”

For example, take the person who identifies so fervently and obsessively with some hobby, profession, or role. It could be the Good Father, the Pious Worshipper, the Patriot, and so on. Everything they do in life is subject to this prefabricated identity they wear, and their every action must satisfy a social-facing role. The Pious Worshipper must never tell a ribald joke. The Patriot must never insult her country. The Good Father can never shout and complain about his irrepressibly loud toddler.

These people must fit into a group, a family, or crowd, because that is where they think they will find themselves. They think that doing so is what it means to be a person. But to surrender to the labels of the “finite” is to surrender the complicated capacity you have to reinvent yourself all of the time.

When the finite is all that you live for, you cease to exist as a self. You become a leaf to be blown or a pawn to be moved.

Gawping at possibility

Kierkegaard believed that the finite is not all there is to being human. There is also the infinite — the recognition that we have the capacity to choose and direct our lives in essentially any way we can dream. But spending too much time gawping at the cosmos of possibilities we face is not entirely healthy. For a lot of people, it’s terrifying.

Most of us can remember the anxious vertigo that comes in those “infinite” moments of life, when you leave your parents’ home, end a relationship, or stare at the blank first page of a novel. To know the infinite is also to be dreadfully aware of the vastness of the future. In a phrase Kierkegaard made famous (philosophically famous, anyway), this is to experience and know the “dizziness of freedom.”

For many people, the anxiety and panic that comes from confronting the vast potential of life is crippling. There’s a paralysis that comes in being unable to choose, because there are too many choices to make, and too many potential options to choose from. For so much of our lives we’re led by the hand by those around us, or we’re given easy and impulsive answers from our biology. However, a human is someone who can take stock of things and who can — who has to — make decisions that no one else will make.

Many will lose themselves in the anxiety of just how momentous these choices are. They see how far their decisions will affect everyone around them and they know that you can only choose a path once. Many people will swim too long in the infinite, and, before long, they drown.

The narrow bridge

There is great danger on either side of our walk. We risk losing everything that makes us an individual: a being with choice and freedom. But we also risk never committing to life, through putting off our decisions or denying our capacity to choose. We must take a step along that narrow bridge between the infinite and finite. After all, like a spinning top, we risk toppling and losing our very selves when we stop moving.

Kierkegaard’s advice is that we must each “learn to be anxious.” We must take a stand where we will but get used to facing outward. There’s a paradox in all this (and Kierkegaard is particularly fond of paradoxes) and we must hold two seemingly contradictory beliefs in tandem, while never giving sway to either.

We must recognize that we are puny and insignificant — primates running on hormones and synapses. But we must also recognize that we are powerful beyond belief, that each of our decisions reaches out into the future, and that our decisions define our future. Embracing and living with this paradox is a maturing of the soul and it is a necessary step in becoming a human being. As Kierkegaard wrote, “I will say that this is an adventure that every human being must go through.” We all live in contradiction. Wisdom comes in accepting that.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular account called Mini Philosophy and his first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.