How Many Planets In The Universe?

Given all the stars, galaxies and what we know about the laws governing reality, how many planets are there in our observable Universe?

“Stuff your eyes with wonder, live as if you’d drop dead in ten seconds. See the world. It’s more fantastic than any dream made or paid for in factories.” -Ray Bradbury

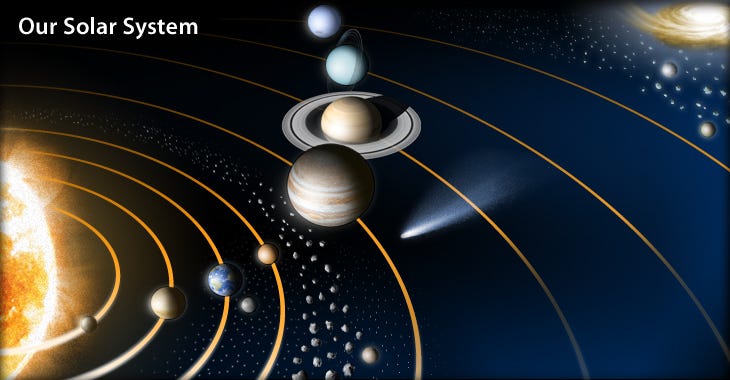

It wasn’t all that long ago — back when I was a boy — that the only planets we knew of were the ones in our own Solar System. The rocky planets, our four gas giants, and the moons, asteroids, comets, and kuiper belt objects (which only included then-planet Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, at the time) were all that we knew of.

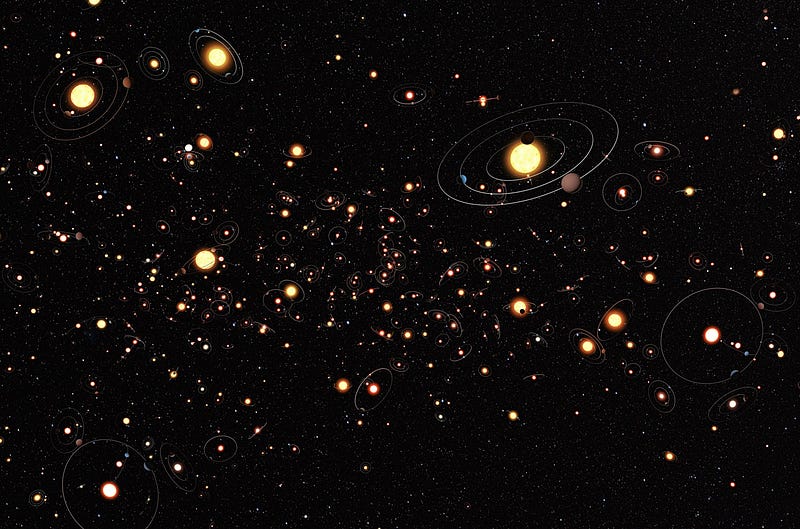

But all of these were just the worlds around our Sun, which houses (according to current definition) eight planets. Our Sun is just one of an estimated two-to-four hundred billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy, and looking up towards the night sky, one can’t help but wonder how many of those stars have planets of their own, and what those worlds are like.

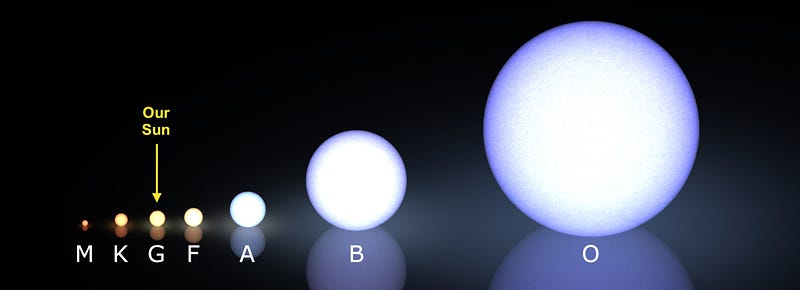

A few decades ago, discussions about planets would have been mostly speculative, and we would’ve focused on theorizing based on the one thing that was well-known at the time: the stars in our galaxy. There are a vast variety of them, in terms of size, mass, radius and color, out there in our galaxy. Our Sun is just one example — a G-class star — of the seven different main types.

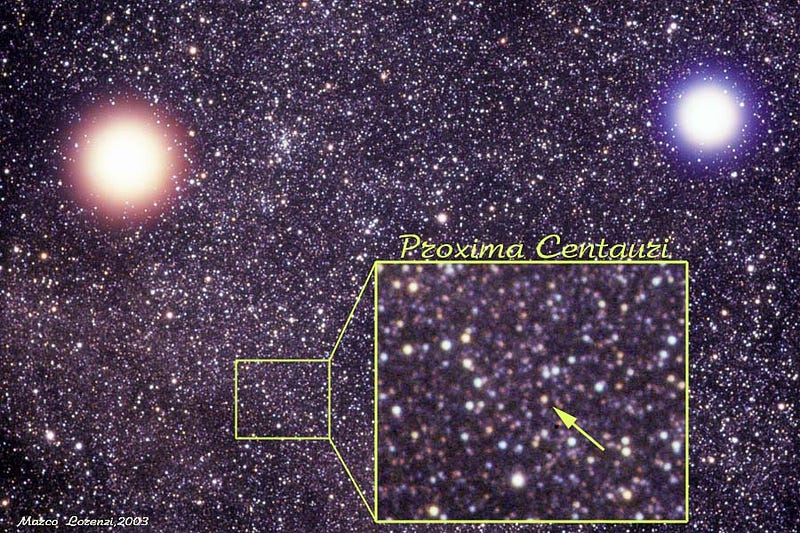

We may think of our Sun as being typical and on the relatively dim side, since a disproportionate number of stars visible to our eyes in the night sky are O, B, and A-class stars, along with the highly-evolved red giants, which aren’t represented on the diagram, above. But there’s a reason those are the stars we see: they’re intrinsically brighter, and so we see more of them! In fact, the closest star to us in the entire night sky — Proxima Centauri — is invisible in anything smaller than mid-sized telescopes.

In reality, the Sun is more massive and intrinsically brighter than 95% of the stars in our galaxy. The red dwarf stars — M-class stars — which range between 8%-to-40% the mass of our Sun, make up 3 out of every 4 stars that are out there.

What’s more than that, our Sun exists in isolation; it is not gravitationally bound to any other stars. But that is not necessarily how stars exist in the galaxy, either.

Stars can be clustered together in twos (binary stars), threes (trinaries), or groups/clusters containing anywhere from hundreds to many hundreds of thousands of stars.

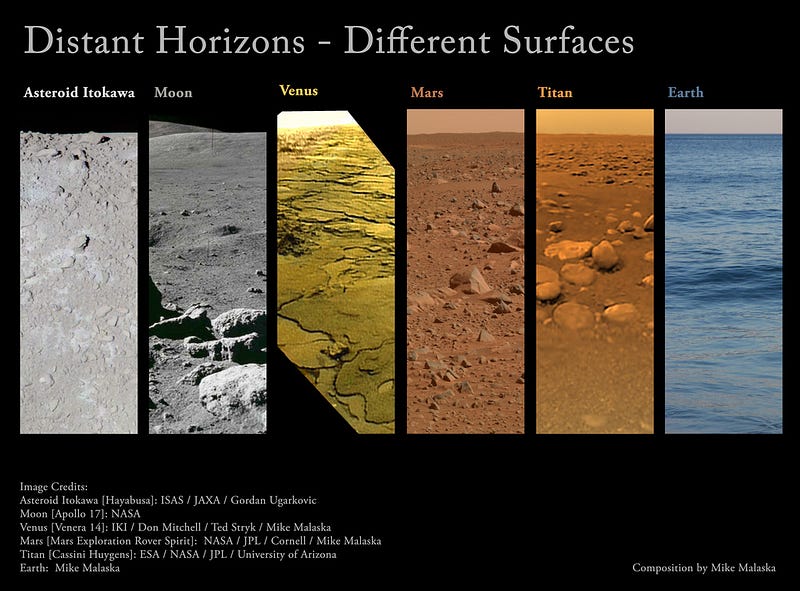

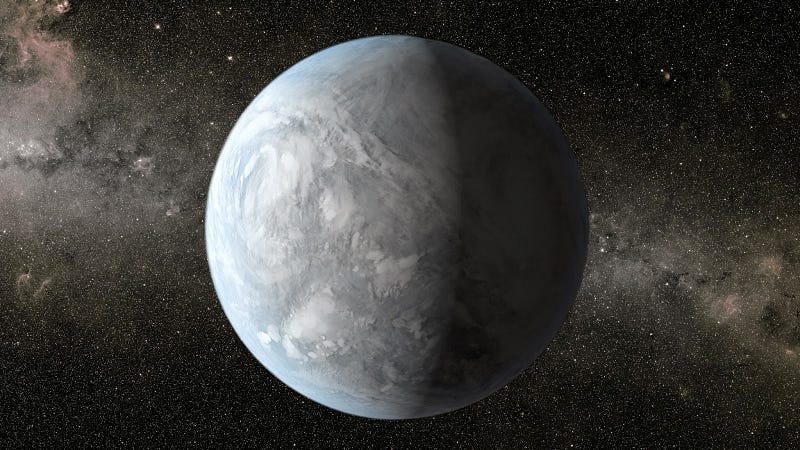

My point is this: if you want to accurately estimate how many planets there are in our galaxy, you can’t just take the number of planets we find around our star and multiply it by the number of stars in our galaxy. That’s a naïve estimate that we’d make in the absence of evidence. But just for fun, that’d give us somewhere around two-to-three trillion planets in our galaxy. (And that doesn’t even count planetary moons!) As we know from our own Solar System, there’s a great variety of what the surfaces of those planets could look like.

But over the past two decades, we’ve been looking. We’ve been looking with a few different methods, in fact, and the two most prolific are the “stellar wobble” method, where you can infer the mass-and-radius of a planet (or set of planets) around a star by observing how it “wobbles” gravitationally over long periods of time:

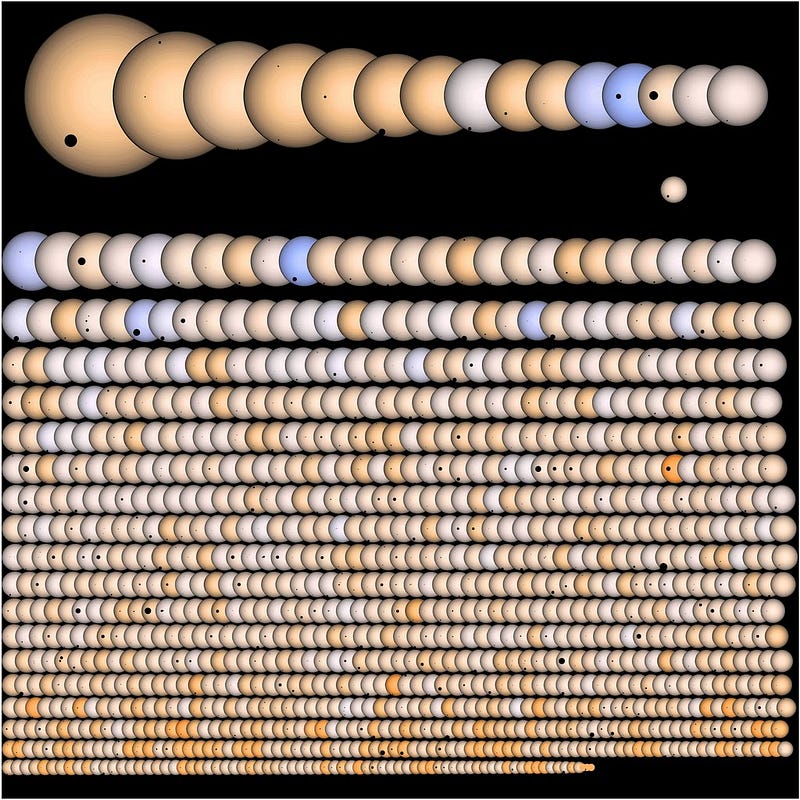

And the transit method, where the light coming from a distant star is partially blocked by the disk of a planet in its solar system passing in front of it.

It’s important to recognize, when we do this, that we will not see the vast majority of planets that are out there. Take NASA’s Kepler Mission, for instance, which has discovered hundreds-to-thousands of planets by looking at a field-of-view containing around 100,000 stars.

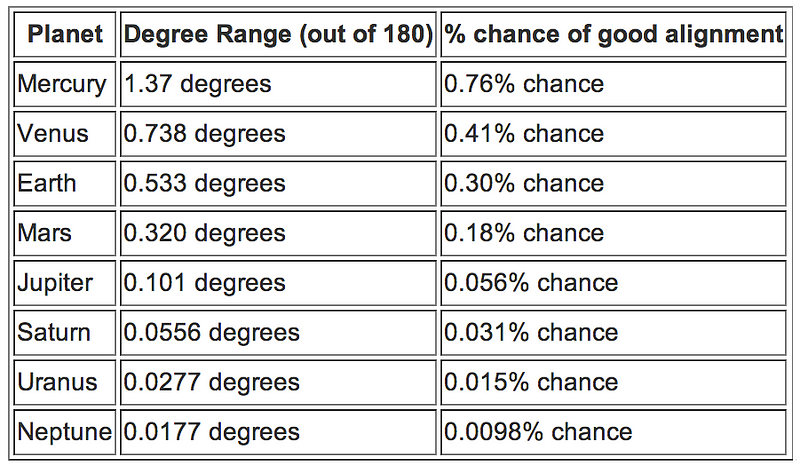

But that does not mean that there are only a few planets-per-hundred-stars. Consider the following: if Kepler were looking at our Solar System, and our Solar System was oriented randomly with respect to our perspective, these are the odds that the alignment would be good enough to observe a transit of our star by one of our planets.

Now you may think those are not-so-good odds, but you don’t even know the half of it. Mercury and Mars are too small, meaning they don’t block enough of the Sun’s light, to be detectable with our best planet-finding technology, and the four outer planets, despite their large sizes, take too long to orbit for Kepler to observe more than one transit, a necessity for dubbing an object “a planetary candidate.”

So this means that if Kepler were looking at 100,000 stars identical to our own, it would have found 410 stars with a total of 700 planets around them.

But as of today, Kepler has found over 11,000 stars with at least one planetary candidate, and over 18,000 potential planets around those stars, with periods ranging from 12 hours up to 525 days. What we’ve learned from this is that there are:

- a huge variety of planetary systems out there, most of which are very different from our own,

- orbiting a wide variety of stars, including binary and trinary systems,

- and we are only seeing the ones that are large enough, orbiting their stars close enough, that also have unlikely, fortuitous alignments with respect to our line-of-sight.

You may have read, relatively recently, that there are at least 100-to-200 billion planets in our Milky Way, and that’s true. But that’s not an estimate; that’s a lower limit. If you instead were to make an estimate, you’d get a number that’s at least one (and more like two, if you’re willing to make inferences about outer planets) orders of magnitude higher: closer to ten trillion planets in our galaxy, alone!

And for those of you wondering, that doesn’t even include the so-called rogue/orphan planets, or planets that exist in the depths of space that aren’t orbiting a parent star. If we included those instead, the number of planets in our galaxy would likely increase by anywhere from a factor of a hundred to a million, meaning there are probably between 10^15 and 10^19 planetary bodies, total, within our galaxy.

In other words, based on what we’ve seen so far, nearly all stars are likely to have planets, and based on what we’ve seen in the inner solar systems of the ones that do, a large fraction of them — particularly the M-class stars — are likely to have more rocky planets in their inner solar systems than even our own has, to say nothing of the outer solar system!

Over time, we’ll continue to learn more and refine our estimates, but right now, there are at least about as many planets as there are stars in our galaxy, and quite probably many, many more than even eight times that number.

Our Solar System may yet turn out to be average, slightly above average, or somewhat below average; we’re still not sure. But regardless of which way it goes, we’re talking about trillions of planets in our galaxy alone. And remember, our galaxy isn’t alone in the Universe.

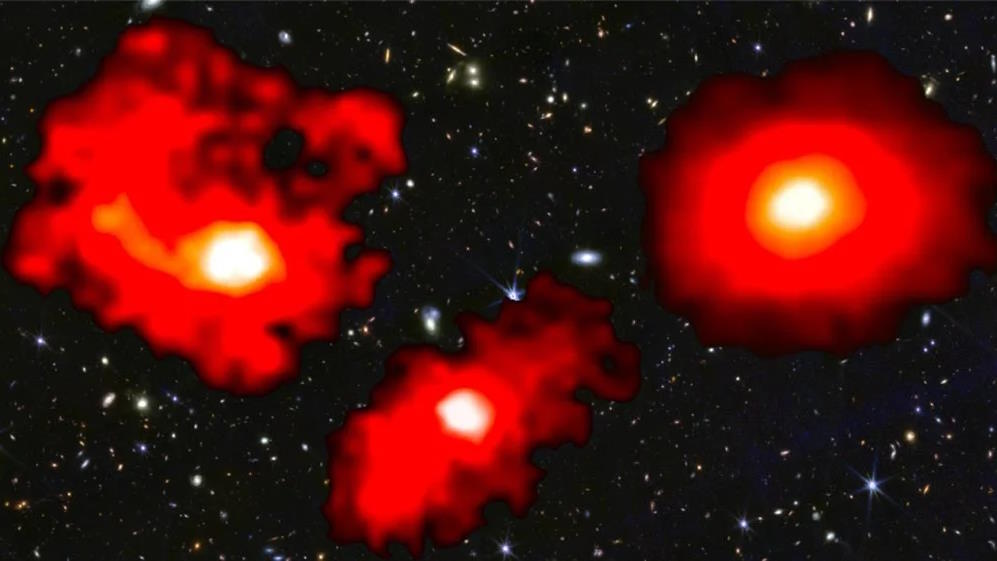

With at least 200 billion galaxies out there (and possibly even more), we’re very likely talking about a Universe filled with around 10^25 planets. For those of you who like to see gigantic numbers written out in full, around 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 planets in our observable Universe, and that’s only counting planets that are orbiting stars.

That number’s only going to get more accurate, but I’m tired of people giving the lowball-estimate when it’s eminently likely that there are so many more. Let’s keep looking, for not just planets, but for water, oxygen, and signs of life. With all of those chances, we’re bound to get lucky if we persevere and look hard enough!

An earlier version of this post originally appeared on the old Starts With A Bang blog at Scienceblogs.