Beyond the two cultures: rethinking science and the humanities

Credit: Public domain

- There is a great disconnect between the sciences and the humanities.

- Solutions to most of our real-world problems need both ways of knowing.

- Moving beyond the two-culture divide is an essential step to ensure our project of civilization.

For the past five years, I ran the Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Engagement at Dartmouth, an initiative sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation. Our mission has been to find ways to bring scientists and humanists together, often in public venues or — after Covid-19 — online, to discuss questions that transcend the narrow confines of a single discipline.

It turns out that these questions are at the very center of the much needed and urgent conversation about our collective future. While the complexity of the problems we face asks for a multi-cultural integration of different ways of knowing, the tools at hand are scarce and mostly ineffective. We need to rethink and learn how to collaborate productively across disciplinary cultures.

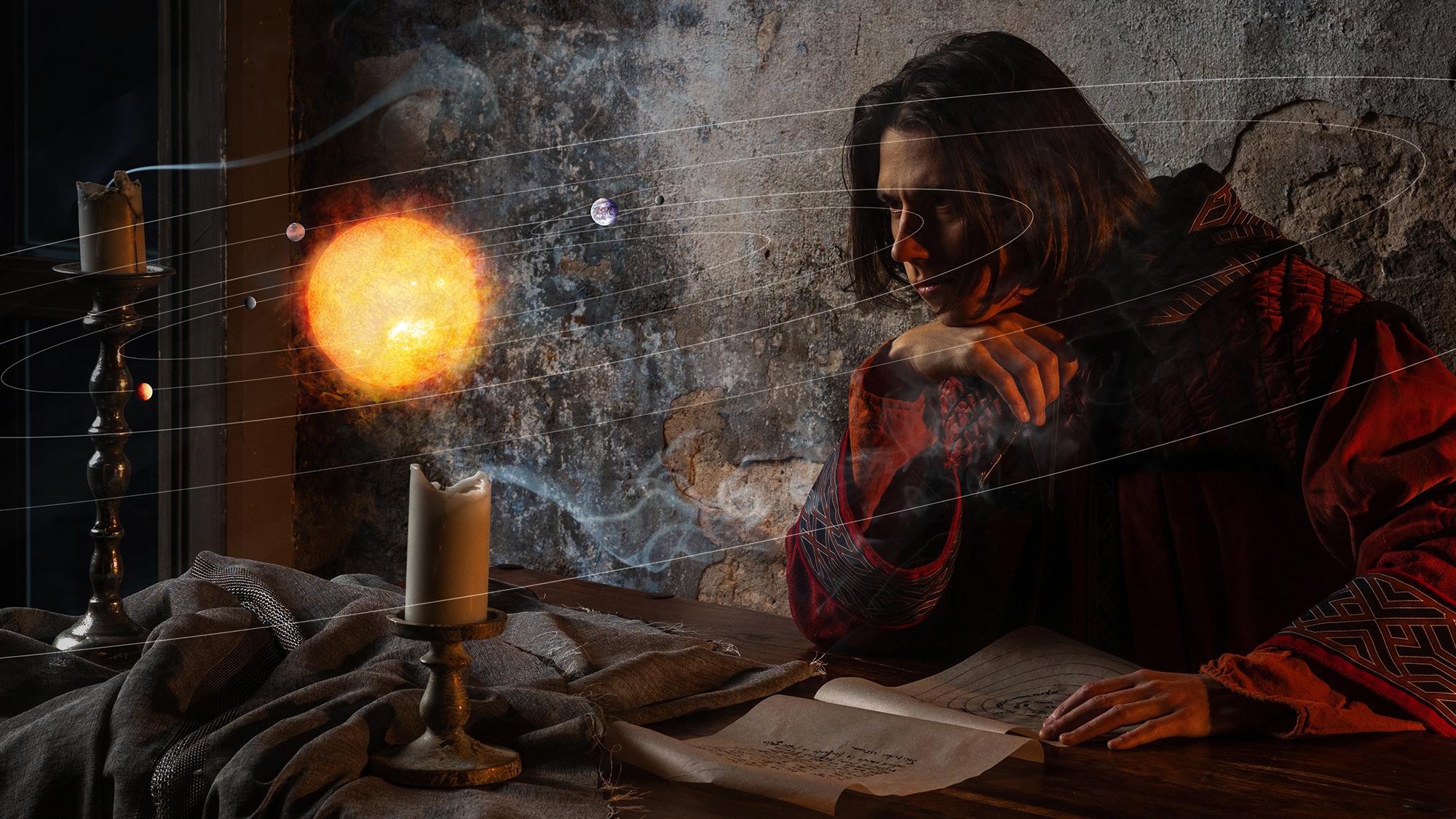

The danger of hyper-specialization

The explosive expansion of knowledge that started in the mid 1800s led to hyper-specialization inside and outside academia. Even within a single discipline, say philosophy or physics, professionals often don’t understand one another. As I wrote here before, “This fragmentation of knowledge inside and outside of academia is the hallmark of our times, an amplification of the clash of the Two Cultures that physicist and novelist C.P. Snow admonished his Cambridge colleagues in 1959.” The loss is palpable, intellectually and socially. Knowledge is not adept to reductionism. Sure, a specialist will make progress in her chosen field, but the tunnel vision of hyper-specialization creates a loss of context: you do the work not knowing how it fits into the bigger picture or, more alarmingly, how it may impact society.

Many of the existential risks we face today — AI and its impact on the workforce, the dangerous loss of privacy due to data mining and sharing, the threat of cyberwarfare, the threat of biowarfare, the threat of global warming, the threat of nuclear terrorism, the threat to our humanity by the development of genetic engineering — are consequences of the growing ease of access to cutting-edge technologies and the irreversible dependence we all have on our gadgets. Technological innovation is seductive: we want to have the latest “smart” phone, 5k TV, and VR goggles because they are objects of desire and social placement.

Are we ready for the genetic revolution?

When the time comes, and experts believe it is coming sooner than we expect or are prepared for, genetic meddling with the human genome may drive social inequality to an unprecedented level with not just differences in wealth distribution but in what kind of being you become and who retains power. This is the kind of nightmare that Nobel Prize-winning geneticist Jennifer Doudna talked about in a recent Big Think video.

At the heart of these advances is the dual-use nature of science, its light and shadow selves. Most technological developments are perceived and sold as spectacular advances that will either alleviate human suffering or bring increasing levels of comfort and accessibility to a growing number of people. Curing diseases is what motivated Doudna and other scientists involved with CRISPR research. But with that also came the potential for altering the genetic makeup of humanity in ways that, again, can be used for good or evil purposes.

This is not a sci-fi movie plot. The main difference between biohacking and nuclear hacking is one of scale. Nuclear technologies require industrial-level infrastructure, which is very costly and demanding. This is why nuclear research and its technological implementation have been mostly relegated to governments. Biohacking can be done in someone’s backyard garage with equipment that is not very costly. The Netflix documentary series Unnatural Selection brings this point home in terrifying ways. The essential problem is this: once the genie is out of the bottle, it is virtually impossible to enforce any kind of control. The genie will not be pushed back in.

Cross-disciplinary cooperation is needed to save civilization

What, then, can be done? Such technological challenges go beyond the reach of a single discipline. CRISPR, for example, may be an invention within genetics, but its impact is vast, asking for oversight and ethical safeguards that are far from our current reality. The same with global warming, rampant environmental destruction, and growing levels of air pollution/greenhouse gas emissions that are fast emerging as we crawl into a post-pandemic era. Instead of learning the lessons from our 18 months of seclusion — that we are fragile to nature’s powers, that we are co-dependent and globally linked in irreversible ways, that our individual choices affect many more than ourselves — we seem to be bent on decompressing our accumulated urges with impunity.

The experience from our experiment with the Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Engagement has taught us a few lessons that we hope can be extrapolated to the rest of society: (1) that there is huge public interest in this kind of cross-disciplinary conversation between the sciences and the humanities; (2) that there is growing consensus in academia that this conversation is needed and urgent, as similar institutesemerge in other schools; (3) that in order for an open cross-disciplinary exchange to be successful, a common language needs to be established with people talking to each other and not past each other; (4) that university and high school curricula should strive to create more courses where this sort of cross-disciplinary exchange is the norm and not the exception; (5) that this conversation needs to be taken to all sectors of society and not kept within isolated silos of intellectualism.

Moving beyond the two-culture divide is not simply an interesting intellectual exercise; it is, as humanity wrestles with its own indecisions and uncertainties, an essential step to ensure our project of civilization.