One year of COVID-19: What will we learn?

Credit: tur-illustration via Adobe Stock / Big Think

- The US is approaching 500,000 COVID-19 deaths. What can we learn from one year of loss and chaos?

- The lessons are clear. Among them are realizing our fragility as a species, our codependence as humans, and the urgent need to move beyond social injustice and inequity.

- As with the Renaissance following the Black Plague of the 14th century and the explosive creativity of the 1920s post Spanish influenza, this is our turn to redefine the course of history. Let’s not mess this up.

It’s been almost a year now since COVID-19 brought the world to a halt. Everyone has been affected, to a degree that varies from the no-so-much to the profoundly tragic. In March 2020, a few weeks into the pandemic, I wrote an opinion piece for CNN where I advanced a few ideas about what changes could unfold due to the challenges ahead. Now that we are well into this mess, and with the growing hope of stepping out of it within the next few months, it’s time to reconsider some of these ideas.

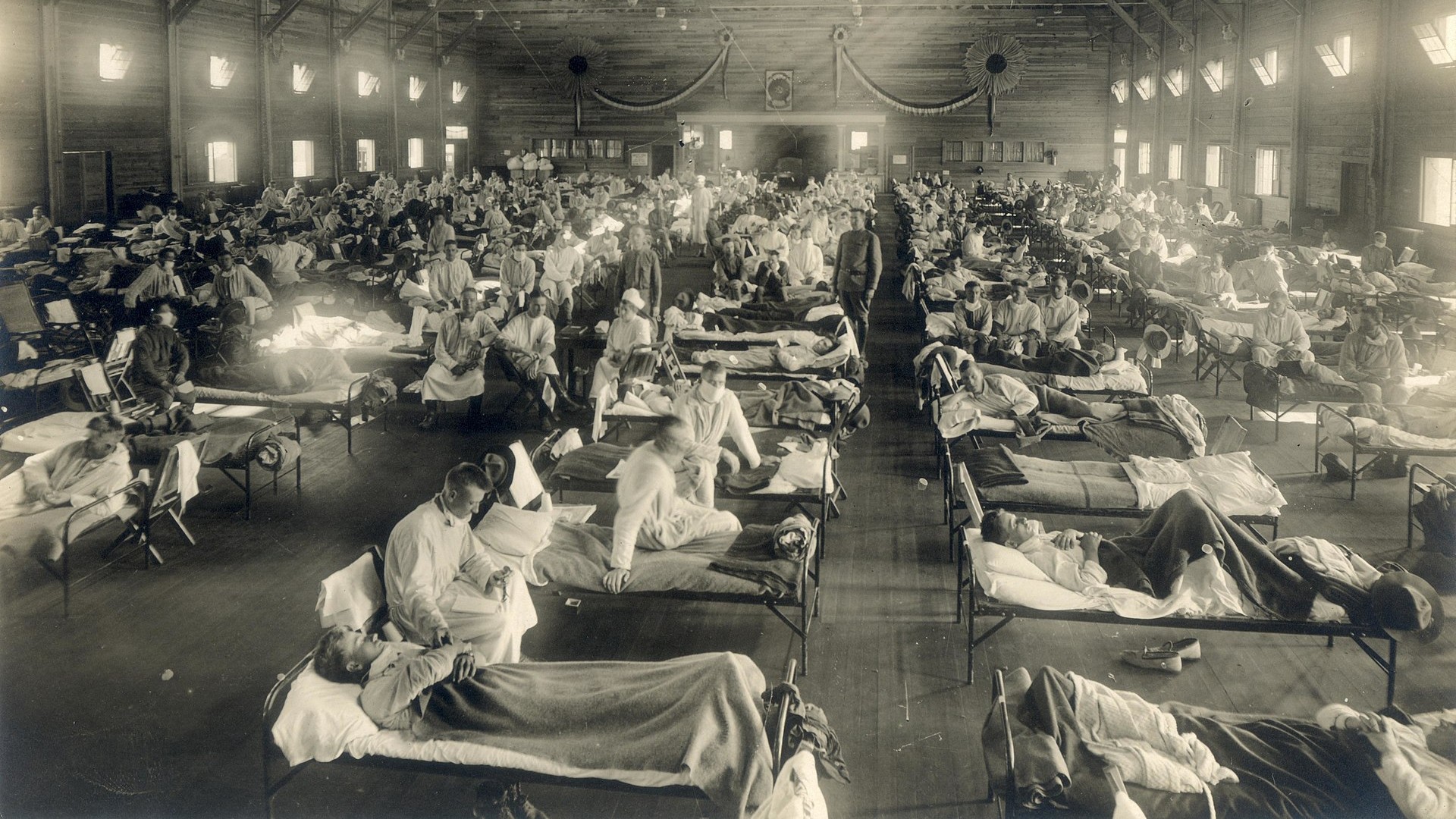

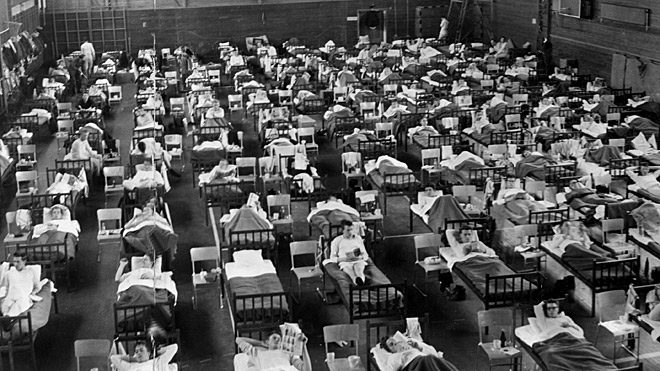

This is the biggest existential threat of our generation. We didn’t face the tragedy of two world wars and, so far, escaped the ongoing threat of nuclear warfare. It’s important to compare the tragedy that we are going through now with the devastation of the Spanish Influenza of 1918, with numbers that seem almost incomprehensible. It is estimated that about 500 million people, some one-third of the world’s population then, were infected by the virus. Of those, 50 million—10 percent—died worldwide, 675,000 of which were in the US. In today’s numbers, this would mean that about 2.4 billion people would be infected, and 240 million would die. At the time of writing, there have been about 109 million confirmed infections (surely an underestimate) and 2.4 million deaths. While the numbers are much better worldwide this time around, this data doesn’t make us feel any better. We are approaching half a million deaths in the US, another incomprehensible number, getting closer to the number of US losses during the Spanish flu. Denial, the lack of federal leadership, the top-down silencing of scientific evidence and support, complacency, science denial—these are all to blame.

A global pandemic of this magnitude is first and foremost a public health issue and the first line of defense is through science and public policy working in tandem. The fact that we are faring comparatively better than in 1918 speaks to the power of medicine to save lives: ventilators, antiviral drugs, better sanitation, better understanding of how this virus operates. The numbers could have been much better if health policy measures had not become politically weaponized and added to the current ideological divide with tragic consequences. The fact that we now have extremely effective vaccines, some using entirely novel technologies, speaks again to the power of science to save lives. This is a moment to celebrate science in service of humanity’s greater good.

Earth has existed for 4.5 billion years; our species, Homo sapiens, has existed for about 200,000 years. Credit: desdemona72 via Adobe Stock

The pandemic has exposed our perennial fragility as a species. Nature operates under rules that don’t include compassion for loss of life. We are not above nature. Technology may give us the impression that we can control the ways of the world, but we are still very much part of the process of natural selection, getting ill as mutant forms of this virus and others create new public health challenges. Natural selection is an endless battle for survival. We cannot trick it into a permanent stop, only into momentary halts. Indeed, as the environment changes, new forms of life emerge and not all of them will be beneficial to us. The melting of the permafrost is bringing up diseases that hit our distant ancestors and against which we are defenseless. Rethinking who we are calls for humility. Humility in the face of our limited resources, humility in the face of forces that are much more powerful than we are. We can dig deep holes and tunnels through mountains, cut down forests and make oceans retreat. But every one of these actions has a profound environmental impact that costs us dearly. Rethinking who we are calls for a reframing of our relationship to the planet. Earth has existed for 4.5 billion years; our species, Homo sapiens, has existed for about 200,000 years. We have just arrived here. Earth will continue without us. We can’t continue without it, space exploration notwithstanding. The future of our project of civilization depends on our rethinking of our planetary role.

The pandemic has given us ample proof of our codependence. We need each other at all levels; the first responders, the farmers and drivers, the supermarket workers bringing food to our tables. It is said that the stability of society is nine meals away. If we don’t eat for 3 days, society unravels. And we need energy, supplies, banking systems, clear roads, clean cities, political stability, news, and fast internet. In a beehive, all workers contribute to the survival of the hive as a whole, every job is important. We are a human hive, and must respect all labor, and ensure that all workers are properly compensated. To live with dignity is not a luxury, it is a right.

The uneven toll of the pandemic has exposed systemic racism and social injustice to levels that can no longer be tolerated or overlooked by anyone, and certainly by those in power. Since at least the origins of agrarian civilization, our ancestors divided into tribes so as to guarantee social cohesion against battling economies. Defined mostly by religious beliefs and social exclusion, such tribal walls have been the signpost of cultures across the globe. We now have a different view of humanity’s place on this planet, our togetherness exposed to us in ways that many dislike. A virus doesn’t care what you believe in, the color of your skin or how much money you have in the bank. It will attack opportunistically and hijack your cellular material to reproduce. But the extent to which people can protect themselves against such attacks does reveal societal inequities in transparent ways. If you share an apartment with eight people and must go to work every day, taking public transportation to get there, you will be walking into the war zone without a weapon or shelter.

With fast internet, it’s abundantly clear that much of the dislocations to and from work, or frequent trips to distant places for meetings, is unnecessary, costly, and detrimental to the environment. Huge expenses with business real estate can be avoided, and funneled into higher compensation for workers and better computer and connectivity equipment. The notion of a downtown where people go to do business is quickly becoming obsolete. Travel will be mostly for fun and adventure. However, for this to become the new normal, fast connectivity and better equipment must be accessible to all, like electricity and clean water (there’s some work still to be done here for sure.) Otherwise, we will be creating another tribal divide (it’s here already), between those who have fast access to information and resources and those who don’t.

The Black Death of the 14th century helped usher in the Renaissance, a spectacular blossoming of human creativity. The Spanish influenza was followed by the Roaring Twenties, an era of explosive cultural dynamism that brought us jazz, Art Deco, and a renewal of our capacity to celebrate life and be productive: automobiles, telephones, aviation, the film industry, electrical appliances, rapid industrial growth. What will be our post-pandemic revolution? The old ways are about to go; they are going already. There is a new world order emerging, the signs are everywhere. Not everyone is willing to see them, or to embark into this new venture. But I hope that those who do will inspire many to follow them. All this loss has to swing around and usher a new page in human history.