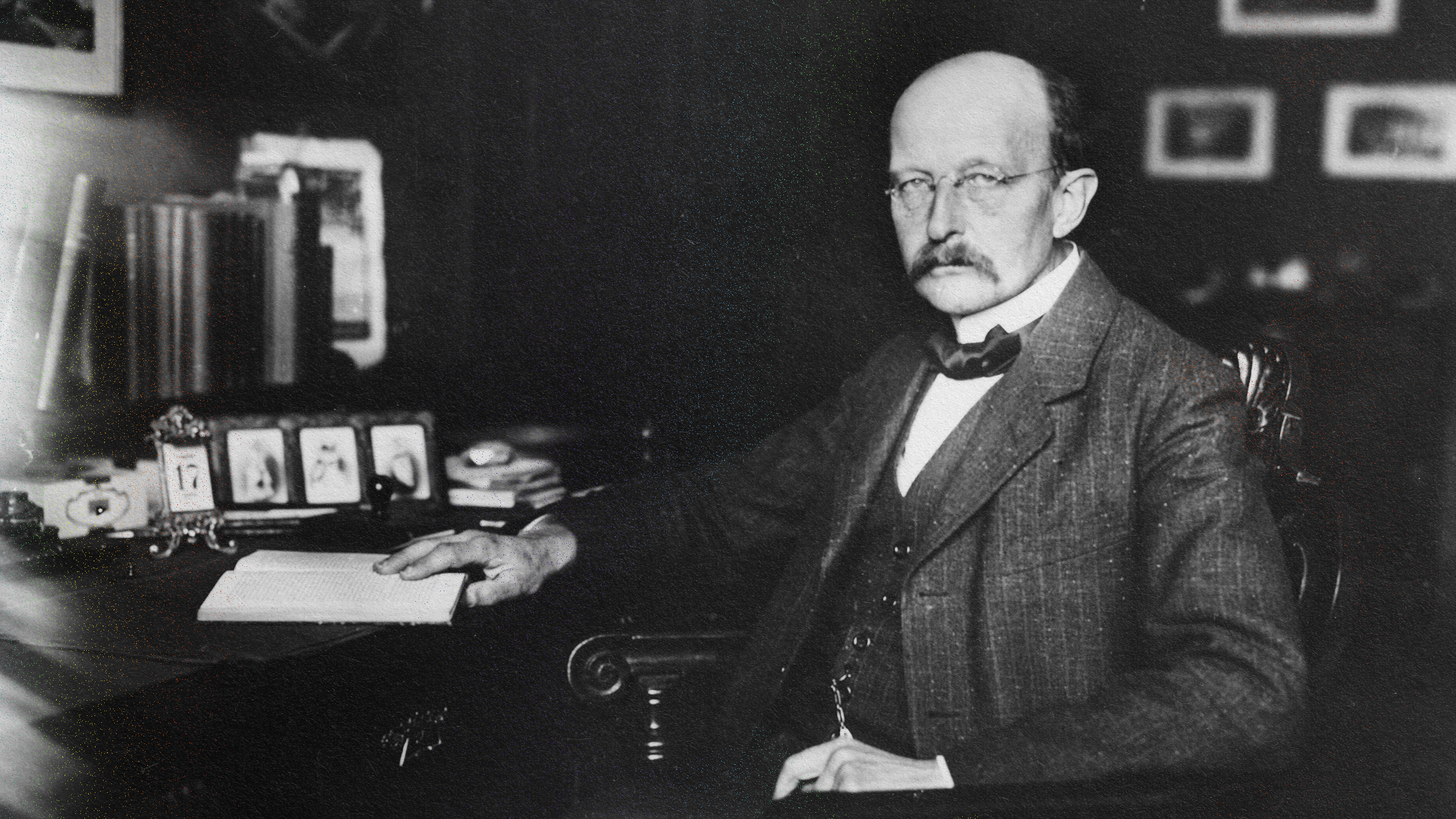

Max Planck and how the dramatic birth of quantum physics changed the world

- Quantum physics was a radical departure from the classical physics of Newton.

- The quantum world is one in which rules that are completely foreign to our everyday experience dictate bizarre behavior.

- Even one of its first discoverers, Max Planck, was reluctant to back the radical conclusions his research led him to.

We now live in the digital era. The scape of technological marvels that surrounds us is something we owe to 100 or so physicists who, at the dawn of the 20th century, were trying to figure out how atoms worked. Little did they know what their courageous, creative thinking would become a few decades later.

The quantum revolution was a very hard process of letting go of old ways of thinking, ways that had framed science since Galileo and Newton. These habits were firmly rooted in the notion of determinism — simply put, scientists held that physical causes have predictable effects, or that nature follows a simple order. The ideal behind this worldview was that nature made sense, that it obeyed rational rules, like clocks do. Letting go of this way of thinking took tremendous intellectual courage and imagination. It is a story that needs to be told many times over.

Unpredictable radiation

The quantum era was the result of a series of laboratory discoveries during the second half of the 19th century that refused to be explained by the prevalent classical worldview, a view based on Newtonian mechanics, electromagnetism, and thermodynamics (the physics of heat). The first problem seems easy enough: Heated objects emit radiation of a certain kind. For example, you emit radiation in the infrared spectrum, because your body temperature hovers around 98° F. A candle glows in the visible spectrum because it is hotter. The question then is to figure out the relation between the temperature of an object and its glow. To do this in a simplified way, physicists studied not hot objects in general, but what happens to a cavity when it is heated up. And that’s when things got weird.

The problem they described came to be known as black-body radiation, the electromagnetic radiation trapped inside a closed cavity. Black-body here simply means an object that produces radiation on its own, without anything coming in. Studying the properties of this radiation by poking a hole in the cavity and studying the radiation that leaked out, it became clear that the shape and material of the cavity do not matter. All that matters is the temperature inside the cavity. Since the cavity is hot, atoms from its walls will produce radiation that will fill the space.

The physics of the time predicted that the cavity would be filled mostly with highly energetic, or high-frequency, radiation. But that was not what the experiments revealed. Instead, they showed that there is a distribution of electromagnetic waves inside the cavity with different frequencies. Some waves dominate the spectrum, but not the ones with the highest or lowest frequencies. How could this be?

A quantum pint

The problem inspired the German physicist Max Planck, who wrote in his Scientific Autobiography that, “This [experimental result] represents something absolute, and since I had always regarded the search for the absolute as the loftiest goal of all scientific activity, I eagerly set to work.”

Planck struggled. On Oct. 19, 1900, he announced to the Berlin Physical Society that he had obtained a formula that nicely fitted the results of the experiments. But finding the fit was not enough. As he wrote later, “On the very day when I formulated this law, I began to devote myself to the task of investing it with a true physical meaning.” Why this fit and not another one?

In working to explain the physics behind his formula, Planck was led to the radical assumption that atoms do not give radiation away continuously, but in discrete multiples of a fundamental amount. Atoms deal with energy as we deal with money, always in multiples of a smallest quantity. One dollar equals 100 cents, and ten dollars equals 1,000 cents. All financial transactions in the U.S. are in multiples of a cent. For the black-body radiation with its many waves of different frequencies, each frequency released relates to a minimum proportional “cent” of energy. The higher the frequency of the radiation, the larger its “cent.” The mathematical formula for this “minimum cent” of energy reads E = hf, where E is the energy, f is the frequency of the radiation, and h is Planck’s constant.

Planck found its value by fitting his formula to the experimental black-body curve. Radiation of a particular frequency can only appear as multiples of its fundamental “cent,” which he later called quantum, a word that in late Latin meant a portion of something. As the great Russian-American physicist George Gamow once remarked, Planck’s hypothesis of the quantum created a world in which you could either drink a pint of beer or no beer at all, but nothing in between.

Quantum blindness

Planck was far from happy with the consequences of his quantum hypothesis. In fact, he spent years trying to explain the existence of a quantum of energy using classical physics. He was a reluctant revolutionary, forcefully led by a deep sense of scientific honesty to propose an idea he was not comfortable with. As he wrote in his autobiography:

“My futile attempts to fit the… quantum… somehow into the classical theory continued for a number of years, and they cost me a great deal of effort. Many of my colleagues saw in this something bordering on a tragedy. But I feel differently about it… I now knew that the… quantum… played a far more significant part in physics than I had originally been inclined to suspect, and this recognition made me see clearly the need for the introduction of totally new methods of analysis and reasoning in the treatment of atomic problems.”

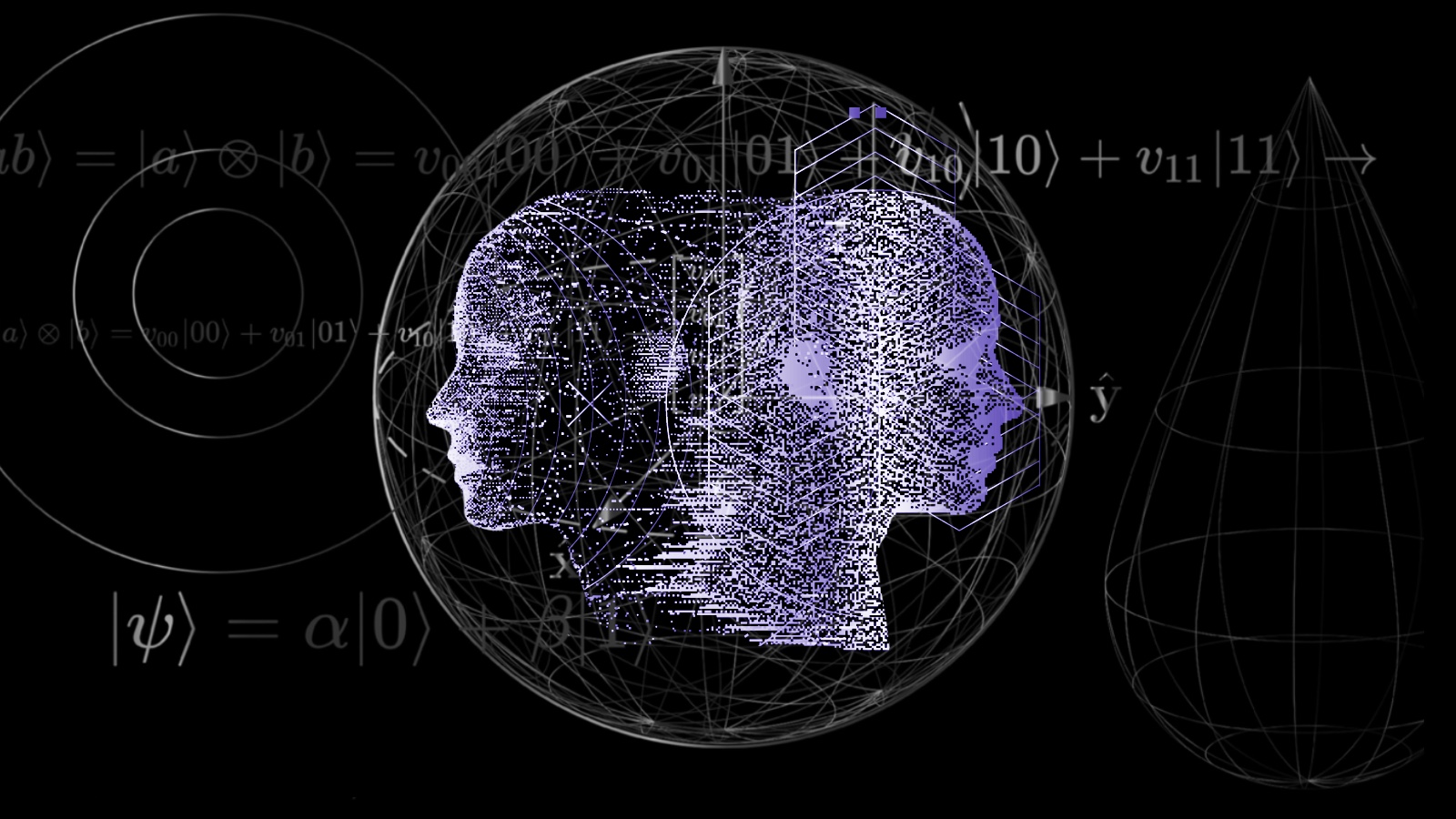

Planck was right. The quantum theory he helped propose evolved into an even deeper departure from the old physics than Einstein’s theory of relativity. Classical physics is based on continuous processes, such as planets orbiting the Sun or waves propagating on water. Our whole perception of the world is based on phenomena that continuously evolve in space and time.

The world of the very small works in a completely different way. It is a world of discontinuous processes, a world where rules alien to our everyday experience dictate bizarre behavior. We are effectively blind to the radical nature of the quantum world. The energies we commonly deal with contain such an enormous number of energy quanta, that its “graininess” obscures our ability to see it. It is as if we lived in a world of billionaires, where a cent is a perfectly negligible amount of money. But in the world of the very small, the cent, or the quantum, rules.

Planck’s hypothesis changed physics, and eventually the world. He could not have predicted this. Neither could Einstein, Bohr, Schrodinger, Heisenberg, and the other quantum pioneers. They knew they had hit on something different. But no one could have anticipated how far the quantum would change the world.