- How far should we defend an idea in the face of contrarian evidence?

- Who decides when it’s time to abandon an idea and deem it wrong?

- Science carries within it its seeds from ancient Greece, including certain prejudices of how reality should or shouldn’t be.

From the perspective of the west, it all started in ancient Greece, around 600 BCE. This is during the Axial Age, a somewhat controversial term coined by German philosopher Karl Jaspers to designate the remarkable intellectual and spiritual awakening that happened in different places across the globe roughly within the span of a century. Apart from the Greek explosion of thought, this is the time of Siddhartha Gautama (aka the Buddha) in India, of Confucius and Lao Tzu in China, of Zoroaster (or Zarathustra) in ancient Persia—religious leaders and thinkers who would reframe the meaning of faith and morality. In Greece, Thales of Miletus and Pythagoras of Samos pioneered pre-Socratic philosophy, (sort of) moving the focus of inquiry and explanation from the divine to the natural.

To be sure, the divine never quite left early Greek thinking, but with the onset of philosophy, trying to understand the workings of nature through logical reasoning—as opposed to supernatural reasoning—would become an option that didn’t exist before. The history of science, from its early days to the present, could be told as an increasingly successful split between belief in a supernatural component to reality and a strictly materialistic cosmos. The Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries, the Age of Reason, means quite literally ‘to see the light,’ the light here clearly being the superiority of human logic above any kind of supernatural or nonscientific methodology to get to the “truth” of things.

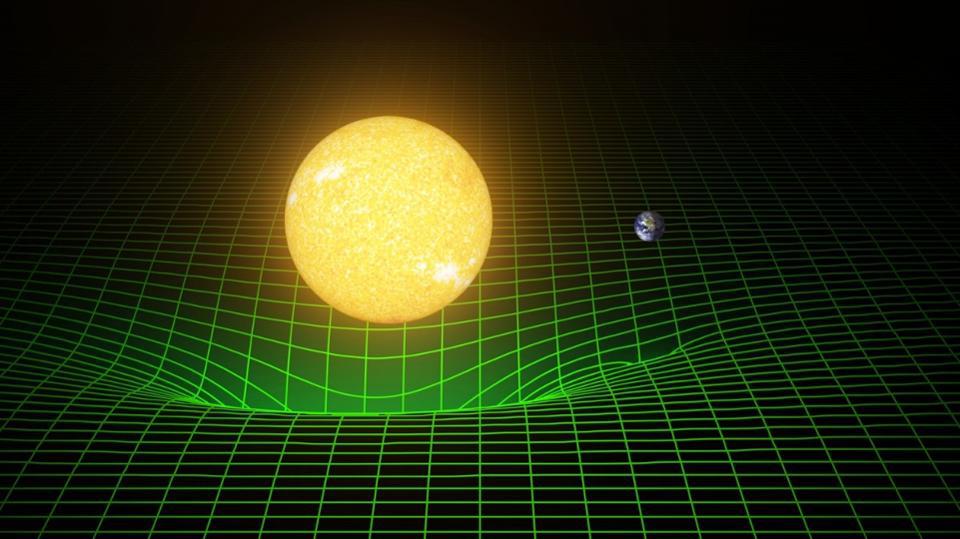

Einstein, for one, was a believer, preaching the fundamental reasonableness of nature; no weird unexplainable stuff, like a god that plays dice—his tongue-in-cheek critique of the belief that the unpredictability of the quantum world was truly fundamental to nature and not just a shortcoming of our current understanding.

To what extent we can understand the workings of nature through logic alone is not something science can answer. It is here that the complication begins. Can the human mind, through the diligent application of scientific methodology and the use of ever-more-powerful instruments, reach a complete understanding of the natural world? Is there an “end to science”? This is the sensitive issue. If the split that started in pre-Socratic Greece were to be completed, nature in its entirety would be amenable to a logical description, the complete collection of behaviors that science studies identified, classified, and described by means of perpetual natural laws. All that would be left for scientists and engineers to do would be practical applications of this knowledge, inventions, and technologies that would serve our needs in different ways.

This sort of vision—or hope, really—goes all the way back to at least Plato who, in turn, owes much of this expectation to Pythagoras and Parmenides, the philosopher of Being. The dispute between the primacy of that which is timeless or unchangeable (Being), and that which is changeable and fluid (Becoming), is at least that old. Plato proposed that truth was in the unchangeable, rational world of Perfect Forms that preceded the tricky and deceptive reality of the senses. For example, the abstract form Chair embodies all chairs, objects that can take many shapes in our sensorial reality while serving their functionality (an object to sit on) and basic design (with a sittable surface and some legs below it). According to Plato, the Forms hold the key to the essence of all things.

Plato used the allegory of the cave to explain that what humans see and experience is not the true reality.Credit: Gothika via Wikimedia Commons CC 4.0

When scientists and mathematicians use the term Platonic worldview, that’s what they mean in general: The unbound capacity of reason to unlock the secrets of creation, one by one. Einstein, for one, was a believer, preaching the fundamental reasonableness of nature; no weird unexplainable stuff, like a god that plays dice—his tongue-in-cheek critique of the belief that the unpredictability of the quantum world was truly fundamental to nature and not just a shortcoming of our current understanding. Despite his strong belief in such underlying order, Einstein recognized the imperfection of human knowledge: “What I see of Nature is a magnificent structure that we can comprehend only very imperfectly, and that must fill a thinking person with a feeling of humility.” (Quoted by Dukas and Hoffmann in Albert Einstein, The Human Side: Glimpses from His Archives (1979), 39.)

Einstein embodies the tension between these two clashing worldviews, a tension that is still very much with us today: On the one hand, the Platonic ideology that the fundamental stuff of reality is logical and understandable to the human mind, and, on the other, the acknowledgment that our reasoning has limitations, that our tools have limitations and thus that to reach some sort of final or complete understanding of the material world is nothing but an impossible, semi-religious dream.

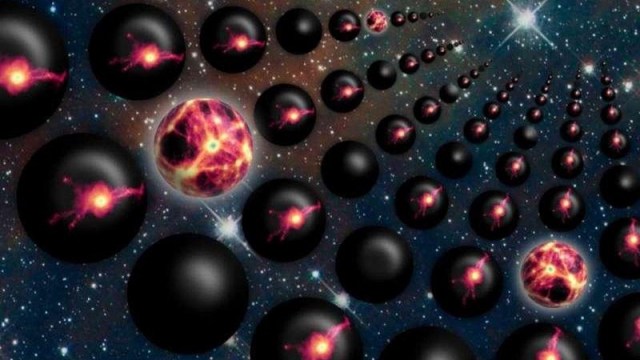

This kind of tension is palpable today when we see groups of scientists passionately arguing for or against the existence of the multiverse, an idea that states that our universe is one in a huge number of other universes; or for or against the final unification of the laws of physics.

Nature, of course, is always the final arbiter of any scientific dispute. Data decides, one way or another. That’s the beauty and power at the core of science. The challenge, though, is to know when to let go of an idea. How long should one wait until an idea, seductive as it may be, is deemed unrealistic? This is where the debate gets interesting. Data to support more “out there” ideas such as the multiverse or extra symmetries of nature needed for unification models has refused to show up for decades, despite extensive searches with different instruments and techniques. On the other hand, we only find if we look. So, should we keep on defending these ideas? Who decides? Is it a community decision or should each person pursue their own way of thinking?

Loose Ends: String Theory and the Quest for the Ultimate Theorywww.youtube.com

In 2019, I participated in an interesting live debate at the World Science Festival with physicists Michael Dine and Andrew Strominger and hosted by physicist Brian Greene. The theme was string theory, our best candidate for a final theory of how particles of matter interact. When I completed my PhD in 1986, string theory was the way. The only way. But, by 2019, things had changed, and quite dramatically, due to the lack of supporting data. To my surprise, both Mike and Andy were quite open to the fact that that certainty of the past was no more. String theory has taught physicists many things and that was perhaps its use. The Platonic outlook was in peril.

The dispute remains alive, although with each experiment that fails to show supporting evidence for string theory the dream grows harder to justify. Will it be a generational thing, as celebrated physicist Max Planck once quipped, “Ideas don’t die, physicists do”? (I paraphrase.) I hope not. But it is a conversation that should be held more in the open, as was the case with the World Science Festival. Dreams die hard. But they may die a little easier when we accept the fact that our grasp of reality is limited, and doesn’t always fit our expectations of what should or shouldn’t be real.