What does the Copernican principle say about life in the universe?

- The Copernican principle, a cornerstone of astronomy, states that Earth is an ordinary planet.

- This principle has been extended improperly, leading some to believe in the triviality of life in the cosmos.

- There is nothing in the original principle that justifies statements about life in the universe. These seem to stem more from philosophical than astronomical considerations.

In physics, principles are like guiding lampposts that allow theories to venture farther. A well-formulated theory is one based on solid principles, usually consisting of generalizations extrapolated from limited observations. Further observations will test and stretch the validity of the principle, until it either breaks or remains validated. Principles are thus essential to how theories work. They summarize knowledge and open ways for further inquiry. For them to remain useful, they must be continually scrutinized.

A typical example of a principle in physics is the principle of relativity devised by Galileo and generalized by Einstein: The laws of nature are the same for all observers (or, more precisely, frames of reference), irrespective of how they move in relation to one another. The principle makes a lot of sense: Science would be impossible if people could not compare their findings about the world in a rationally consistent way.

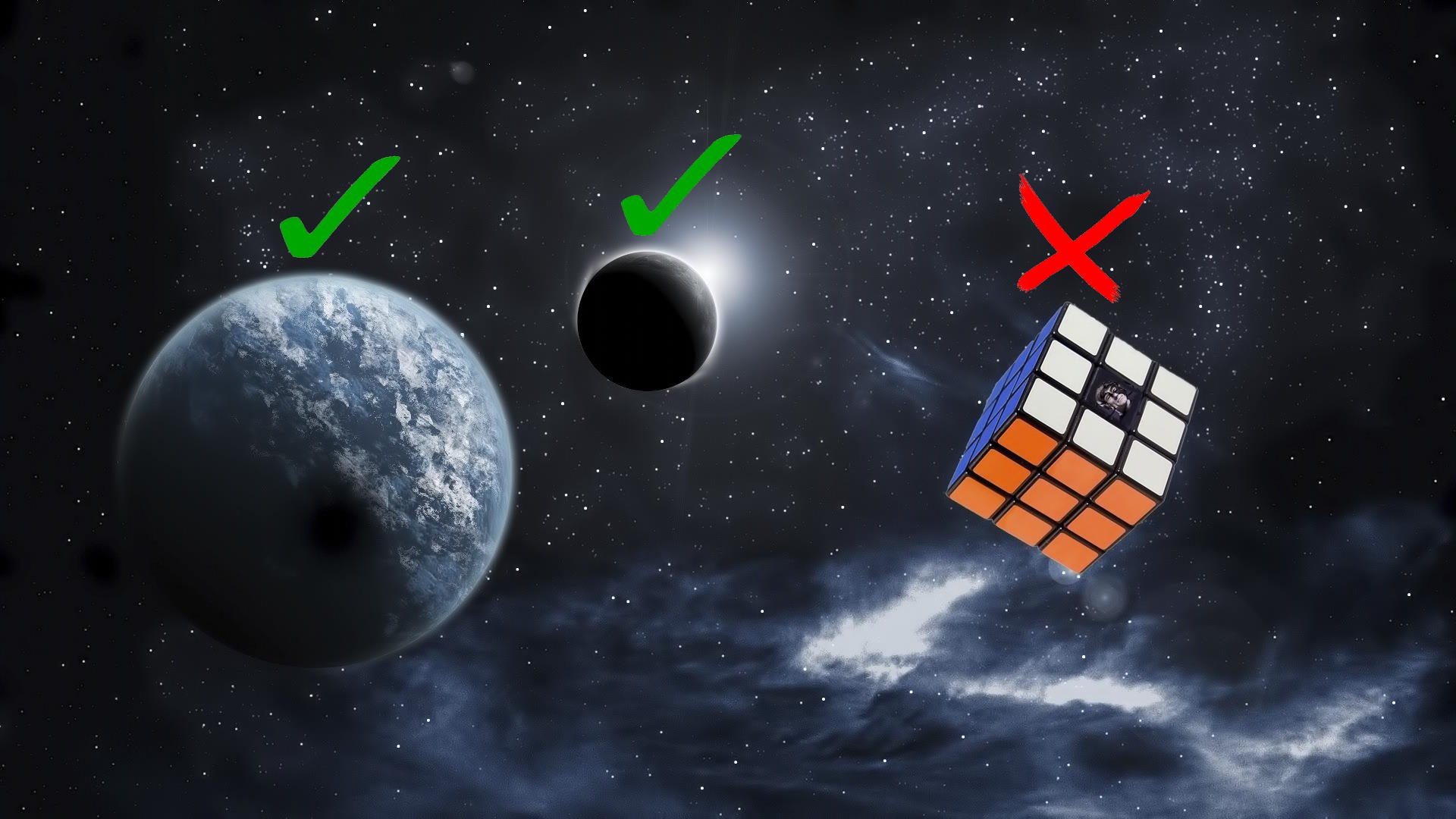

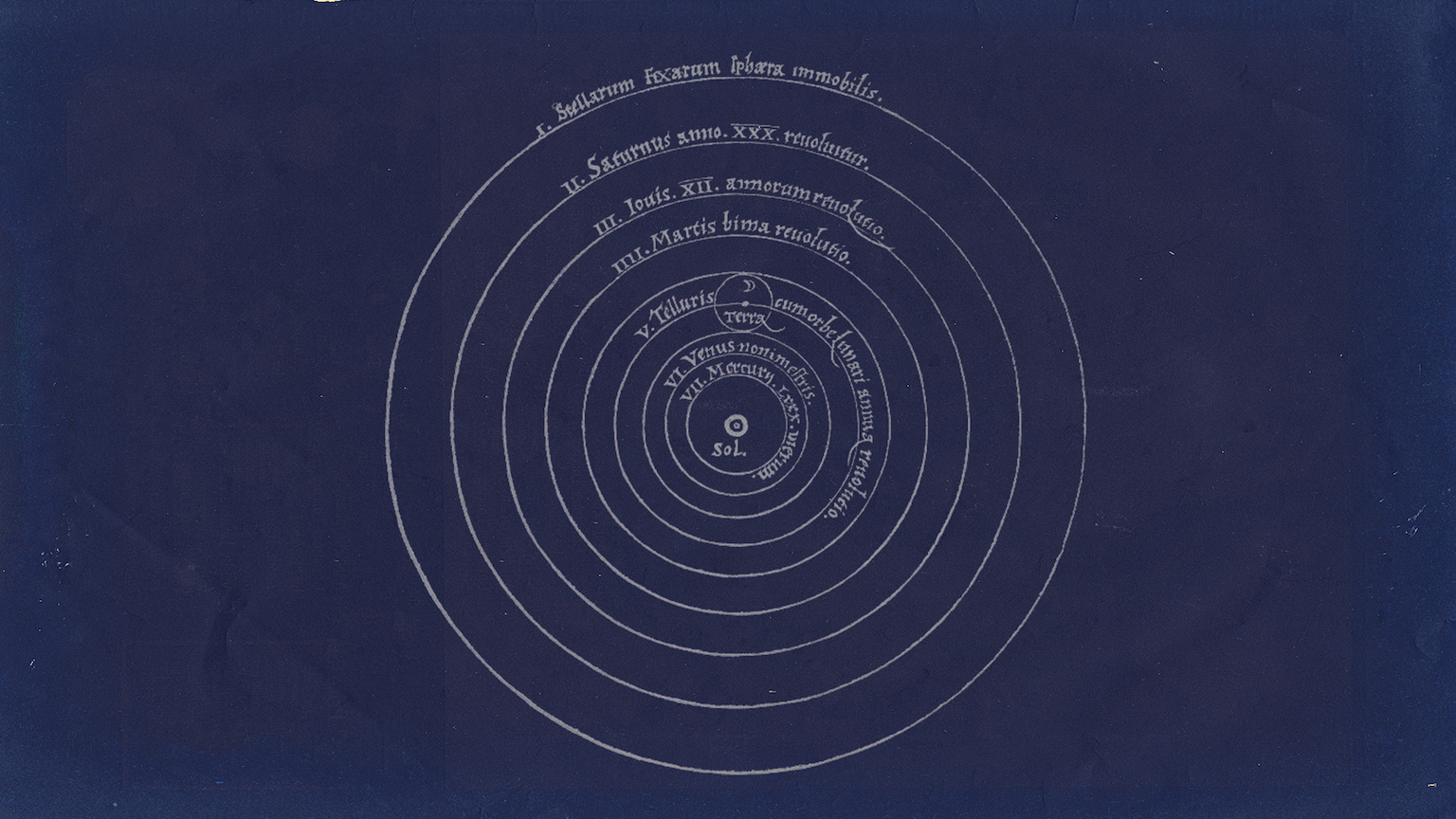

A principle will hold until it doesn’t. In astronomy, an essential principle is the Copernican principle, inspired by the mid 16th-century ideas of Nicolaus Copernicus. Copernicus famously proposed that Earth was not the center of the universe; the sun was. The Earth, he suggested, was just another planet orbiting the sun like Mars or Jupiter. Apart from the now obvious step in the right direction concerning the nature of our planet, the principle has a more profound, even if less justified, consequence: by equating Earth with other planets, it removed its exceptional place in the cosmic order and, with it, that of us humans as well. The principle, as understood today, is usually stated as, “Earth is an ordinary planet, and we, human observers, are ordinary too.” There is nothing special about either Earth or our species.

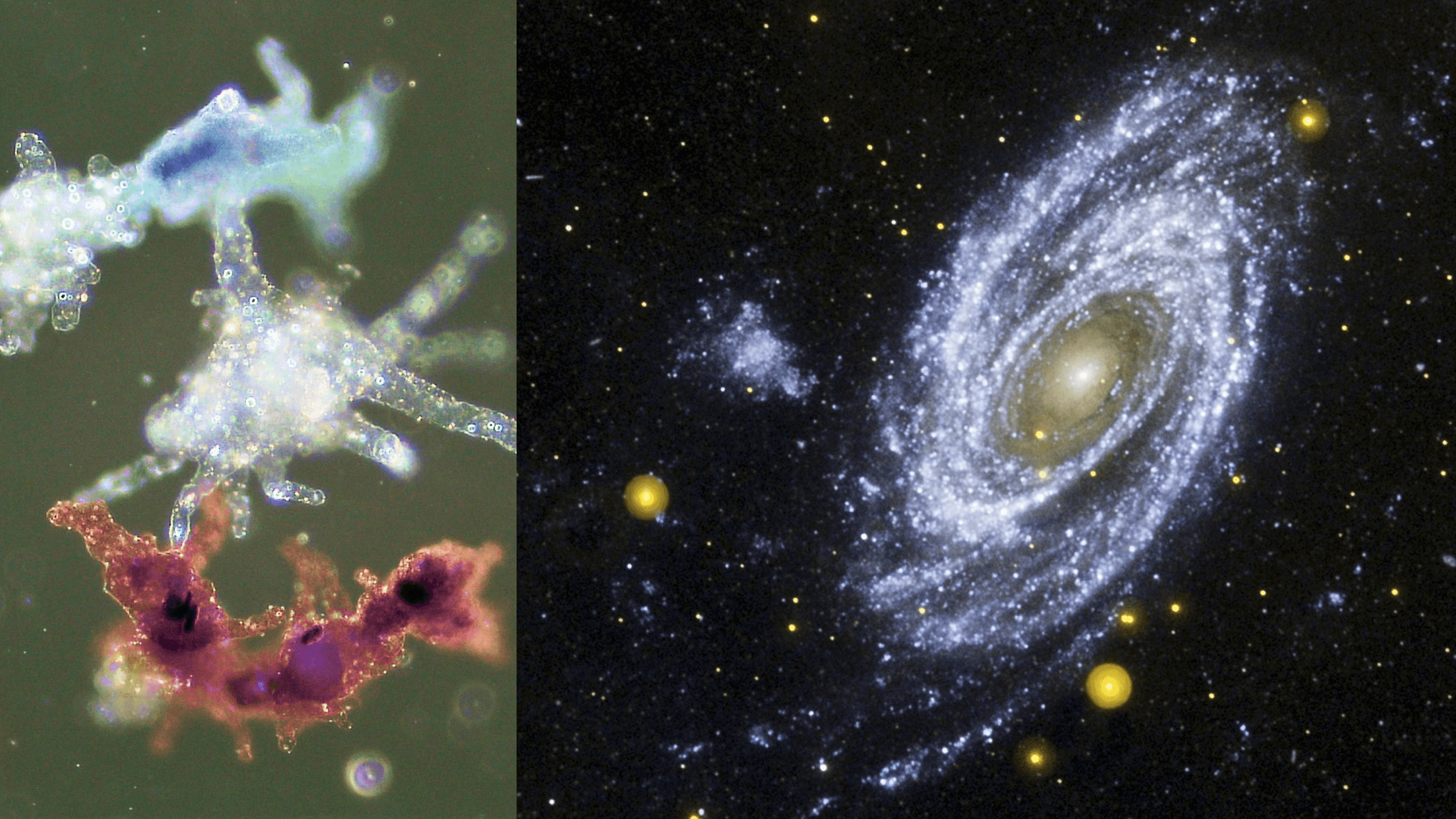

However, such statements are scientifically unjustified, and the meaning of the principle is often confused. We currently do not know enough about exoplanets to make a statement about how special Earth is. And we know far less about the possible existence of life in other worlds and about what kind of life that would be. So, to blindly extend the Copernican principle to guide our thoughts about Earth in comparison to other worlds when it comes to habitability is not just a false extrapolation but also imprudent. We simply do not know enough to make such pronouncements.

As an aside, it is also incorrect to equate the Copernican principle with a cry against human exceptionalism. The principle says nothing about the nature of life or about any implicit hierarchy that would erroneously place humans at the apex of Creation. Instead, it relates first to Earth as being a planet — which is indisputable — and, at a second level (more related to a post-Copernican theology than astronomy), to dethrone humanity as a sort of God-chosen species. Humans do not appear to be at the apex of Creation, being instead part of the complex web of life. Human hubris has led us into some very dark existential risks, and those are indeed consequences of the notion of human exceptionalism. But they have little to do with the Copernican principle.

The danger of the Copernican principle is to take it as some sort of final statement about our planet and life on it. As remarked above, we currently do not know enough about the distribution of exoplanets and how Earth-like they are — in the sense of having the correct biochemistry and geophysics to support life — or about how life could manifest itself in other worlds. A principle is a lamppost for further search and not a statement of final truth.

For example, if we were to look only at the planets in our own solar system, Earth is exceptional indeed. Not for orbiting the sun, as all planets do that, but for offering spectacular conditions for life to thrive. The Copernican principle does not take into account the relative position of a planet in the habitable zone of a star or any knowledge about how common or rare life is in the universe. Given that, the only conclusion we can take from the principle with certainty is related to the non-centrality of the Earth; that is, Earth is indeed a planet orbiting the sun like our solar system neighbors.

That, by the way, was all that Copernicus was after. It is not very exciting to people in the 21st century. The more theological conclusion about human non-exceptionality conflates many unknowns about life in the universe and had more to do with Giordano Bruno’s speculation that every star was a sun with planets and living creatures than with Copernicus’s rethinking of the order of the planets due to their orbital periods (that is, the time it takes a planet to complete a revolution about the sun).*

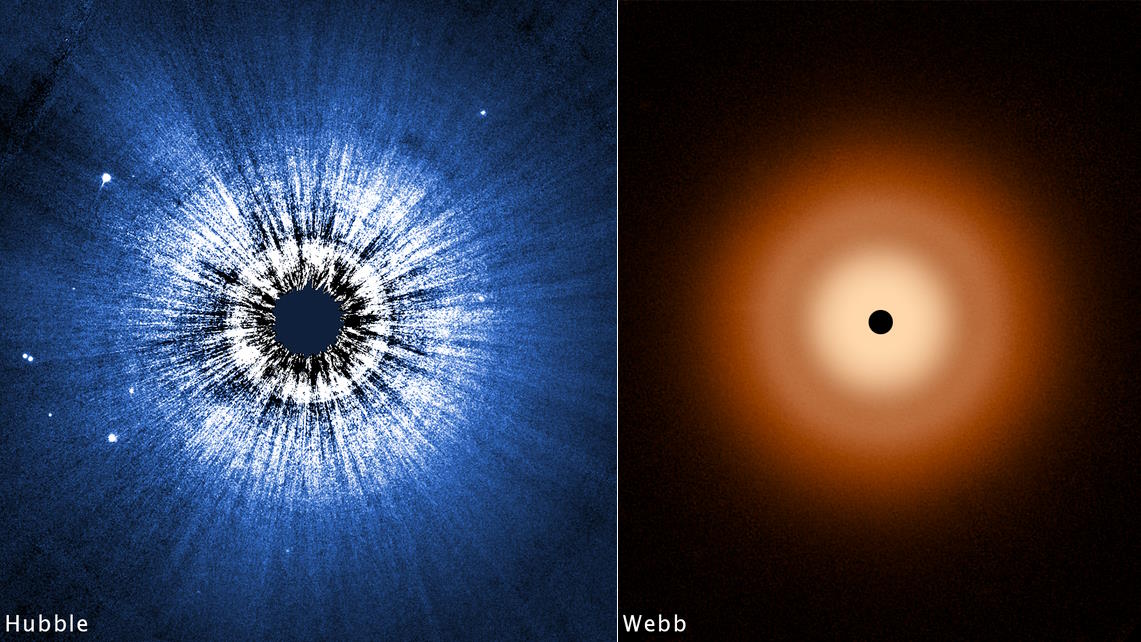

The astronomical part of the Copernican principle is solid, even if less interesting. The life-related part is not. To say something more definitive about the prevalence of life in the universe, we will need more data. As I remarked last week, the James Webb Telescope, and future projects like the Giant Magellan Telescope, offer hope that we will be able to at least learn enough about the atmospheric chemical composition of exoplanets to make statements about their habitability. Still, habitability does not translate into life, and much less into intelligent life, in particular to civilizations with technologically savvy observers. For that, we need different kinds of data, data that has little to do with the Copernican Principle.

*Note: In the near future, I will address the extension of the Copernican principle into the Cosmological principle and the Principle of Mediocrity.