The Poem That Dragged Us Out of the Dark Ages

What’s the Big Idea?

Pity the poor Epicurean. At best, we imagine him with eyes closed, swishing a fine wine around in his mouth in a state of semi-religious ecstasy. At worst, he’s a flatulent, porcine sot splayed out on a couch. What he really is, as Stephen Greenblatt tells us in his fascinating new book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, is the victim of one of the more effective spin jobs in history, a vicious, centuries-long ad campaign motivated primarily by religious politics. For Greenblatt, Epicurian philosophy is the spiritual forbear not of Food and Wine magazine, but of the entire modern world.

The Swerve tells the story of the rediscovery of On the Nature of Things, a multi-volume philosophical poem by Lucretius. Written in the 5th century CE, this Epicurean masterpiece remained buried in a monastic library for a millennium until a book-hunting humanist named Poggio Bracciolini rediscovered it and unleashed its intellectual tsunami on the world.

It’s easy to see why emerging Christianity saw Epicureanism as a threat and decided to paint it as a pit of worldly decadence. Lucretius’ masterwork contains in utero most of the key ideas that define a modern worldview in which gods play no part in our lives. Among them:

Atheism: Lucretius was not exactly an atheist, but he viewed the gods as completely unconcerned with human affairs. He (like Epicurus before him) mocked superstition. He did not believe in “intelligent design” or an afterlife, viewing the soul as a composite of tiny particles that disperse at death.

Microbiology, Atomic and Subatomic Physics: On the Nature of Things views all things as composed of tiny particles that collide randomly, creating and destroying the physical forms of people, plants, and planets.

Evolution: Over centuries, Lucretius says, these endless collisions result in increasingly complex forms. Those that are best suited to their environments survive and reproduce, while others disappear.

What’s the Significance?

Lucretius and his hero Epicurus were not hedonists. They were humanists. Unmoved by theological consolations and warnings they turned their attention to pleasure as the highest good. And while they may have enjoyed a nice glass of wine now and then, they rarely ended up in the vomitorium. Pleasure, for Epicurians, was to be found in modest living, lifelong learning, and freedom from the illusion that wealth, sex, or power can complete you.*

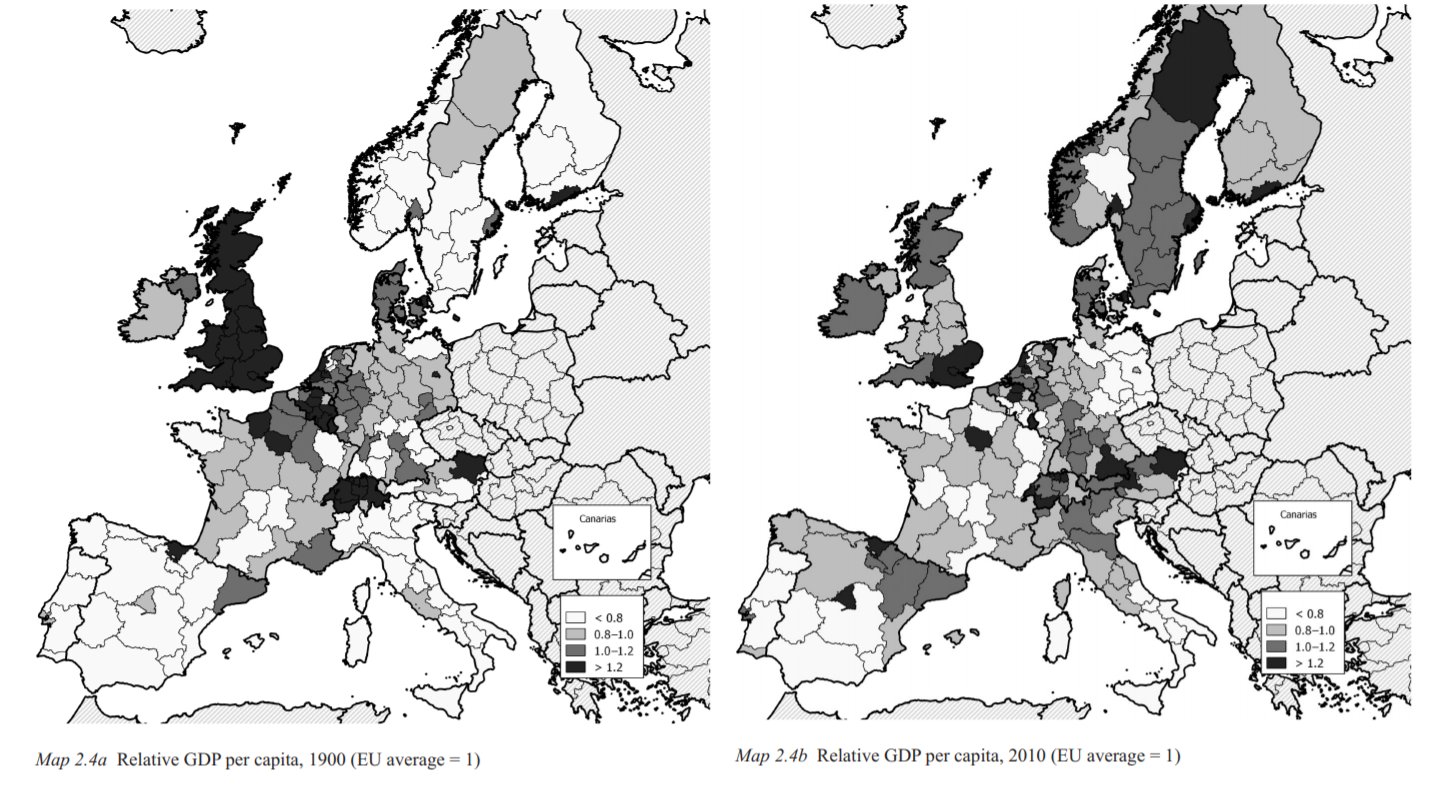

Centuries after Poggio’s great discovery, the landscape is muddy. The great wars of the 20th century, the growing pains of industrialization, and the cultural politics that arose in their wake have left the Enlightenment project of self-improvement through Reason in tatters. Technology and commerce march on, but there is little consensus as to where we’re headed and why. Even medicine, which has increased the average life expectancy in the developed world by thirty years since 1900, has become highly politicized, a symbol for some of a corporate Establishment whose products are suspect, even deadly. This vacuum of distrust and uncertainty leaves us vulnerable, once again, to false prophets on the one hand, self-interest and isolationism on the other.

A richly imagined recreation of a forgotten history, Greenblatt’s book serves as a reminder that Western culture once experienced a kind of awakening – a collective (if not universal, or perfect) belief that science and art were not irreconcilable forces, and that, applied with discipline and intelligence, they could improve our lives.

*This last edges remarkably close to the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism.

Photo Credit: Zlatko Guzmic/Shutterstock.com