The Fool’s Head Map: a Fossil of the Financial Bubbles of 1720

For better or worse, there is little new under the sun [1]. The real estate bubble that burst in 2008 and kicked off the Great Recession may have seemed like fresh horror to many. But it was only the latest example of a basic economic principle: what goes up, tends to go up too high, and will then inevitably come crashing down. Be it the inflated price of houses, of dot-com companies (2000) or of tulips (1637).

The term bubble seems a natural, appropriate description of this cyclical escalation of speculation: its spectacular growth is based solely on air, and will burst suddenly, leaving nothing. Yet it came to be applied to the nosedive at the end of a boom-and-bust cycle specifically in the 1720s, with the bursting of the famous South Sea Bubble [2]. Stock in the South Sea Company, founded in 1711 to trade between Britain and Spanish South America, became subject to frantic speculation: in a single year, share prices rose from £100 to £1,000 – to come tumbling down in 1720. Innumerable personal fortunes were wiped out, many businesses were forced into bankruptcy.

Even back in the early 18th century, the economies of Europe were less ‘national’ than might be suspected. In France, a similar bubble had been growing – and burst at exactly the same time. The Scottish economist/gambler John Law created a Mississippi Bubble by inflating the value of a series of companies trading in Louisiana, France’s giant but underdeveloped American colony [3]. Stock prices shot up from 500 to 18,000 French pounds. When this bubble too burst in 1720, Law was forced to flee across the border in disguise. He died a pauper in Venice.

The bursting bubbles had consequences beyond France and England. In the Netherlands, a few smaller, but similar schemes also collapsed. This Dutch hand-coloured copperplate engraving mocks the flawed thinking behind bubble economics, also known as the Greater Fool Hypothesis: no matter how inflated the price of a given commodity, somewhere out there is an idiot who’ll pay even more for it.

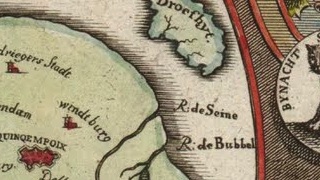

Published anonymously in Amsterdam in 1720, this topical satire shows an “afbeeldinghe van ‘t zeer vermaerde Eiland Geks-Kop” (Image of the Very Famous Island of Fool’s-Head). Unlike many other satirical maps [4], it is not based on existing political or natural borders. The island is a match for its name: a fool decked out with the attributes of folly: asses ears and a fool’s cap. The signifier and the signified [5] are identical.

Four rivers run off the island: the Maas (Meuse), Teems (Thames) and Seine, representing the three countries most affected by the financial meltdown; and the Bubbel. The island is dotted by cities with telling names: Bedriegers Stadt (‘Charlatan City’), Leugenburg (‘Lie Town’), Sottenburg (‘Crazy Town’), Bederfwyk (‘Corrupt Quarter’), and others. The capital, in the centre of the island, is called Quinqempoix, after the Paris street that housed John Law’s company. The main island is surrounded by three smaller ones: Armoed (‘Poverty’), Droefhyt (‘Sadness’), and Wanhoop (‘Despair’).

The cartouche, below the map, completes the description of Geks-Kop: ‘Lying in the sea of shares, discovered by Mr Law-rens, and inhabited by a collection of all kinds of people, to whom is given the general name shareholders’. The coat of arms over the map enshrines the tragic year of 1720.

The scenes on either side further illustrate folly and its consequences. The wheeled land-vessel shown on the right is but one of the many other far-fetched schemes popular at the time. The flag it flies reads Na Vianen (‘To Vianen’), the location of a notorious madhouse. The mob on the left is storming the offices of John Law’s company, in the vain hope of exchanging their worthless stocks for money.

Two thumbnail pictures, top left and top right, provide rather gloating miniatures of the individual misery caused by the burst bubbles. The man on the left exclaims: O jammer en elend hoe kom ik hier te pas (“O sorrow and misery, how will I survive this?”), the right one intones: Ik heb myn geld voor wind gegeven maer van de wind kan ik niet leven (“I exchanged my money for wind, but I can’t live on wind”). Across the centuries, their fossilised despair strikes us with uncanny familiarity.

The hand-coloured version of this map found here on the German-language blog Septentrio. But credit is due to Tim Bryars, who drew my attention to this map on his own, very entertaining map blog, Unto the Ends of the Earth. Tim is a passionate, knowledgeable cartophile – and an enviable one: he has his very own map store [6]. If you’re anywhere near London: vaut le détour!

Strange Maps #554

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] The original phrase in Ecclesiastes 1:9 is a bit more categorical: ‘no new thing under the sun’ (nihil novi sub sole). But that was before iPhones.

[2] Earlier bubbles were often described as ‘manias’, e.g. the Dutch tulipmania (cf. sup.) which saw single tulip bulbs being traded for up to 4,000 guilders – over 10 times the average annual wage.

[3] Hence also ‘Louisiana Bubble’.

[4] The anthropomorphic maps that were popular in the run-up to the First World War, described in #227, are but one example.

[5] See Ferdinand de Saussure’s theory on signifiant and signifié.

[6] In Cecil Court, a stone’s throw from Leicester Square. J.K. Rowling fans might recognise the pedestrian book and map lover’s paradise as Diagon Alley – but please, do not utter any reference to Harry Potter in the presence of Mr Bryars or any of the other shopkeepers, as it will cause them to sigh deeply and lament what the world is coming to.