How NASA is using personality psychology to pick astronauts for a Mars journey

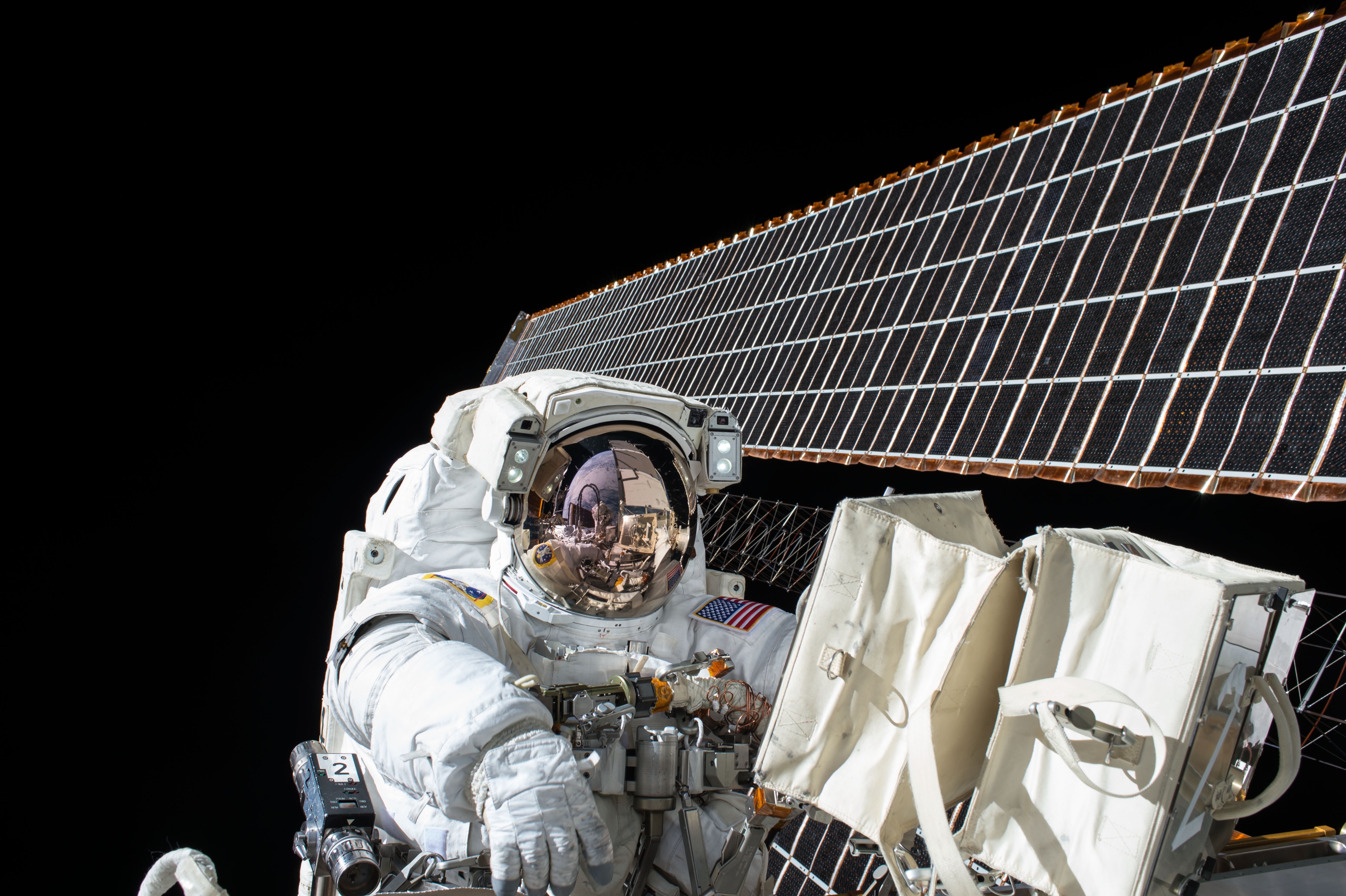

The space industry has a good idea of the technological hurdles it has to climb before embarking on a Mars voyage, but what about those which are psychological?

A new paper published in American Psychologist provides an overview of NASA research on the personality traits necessary for being a good astronaut, and shows what the agency still has to learn before sending humans to the red planet.

There’s one insurmountable problem facing researchers: No one has ever attempted a trip to Mars. Sure, we know that the journey would necessarily entail being crammed in a ship much smaller than the International Space Station (ISS) for two to three years with little communication to family or mission control. But intellectualizing those conditions and experiencing them are very different. That’s not to say space agencies haven’t conducted long-term experiments to simulate the conditions, such as HERA at the Johnson Space Center, or HI-SEAS on the top of the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii, where simulations have lasted up to a year.

“It was a bit overwhelming at first,” saidMartha Lenio, commander of the HI-SEAS mission. “We didn’t really know where to look or what to say. Having all these people around is a bit difficult.”

The main limitation of studies like this is the absence of real danger. The participants know that they’ll be evacuated from the experiment if anything goes wrong, a luxury that can’t be afforded to astronauts traveling millions of miles from Earth.

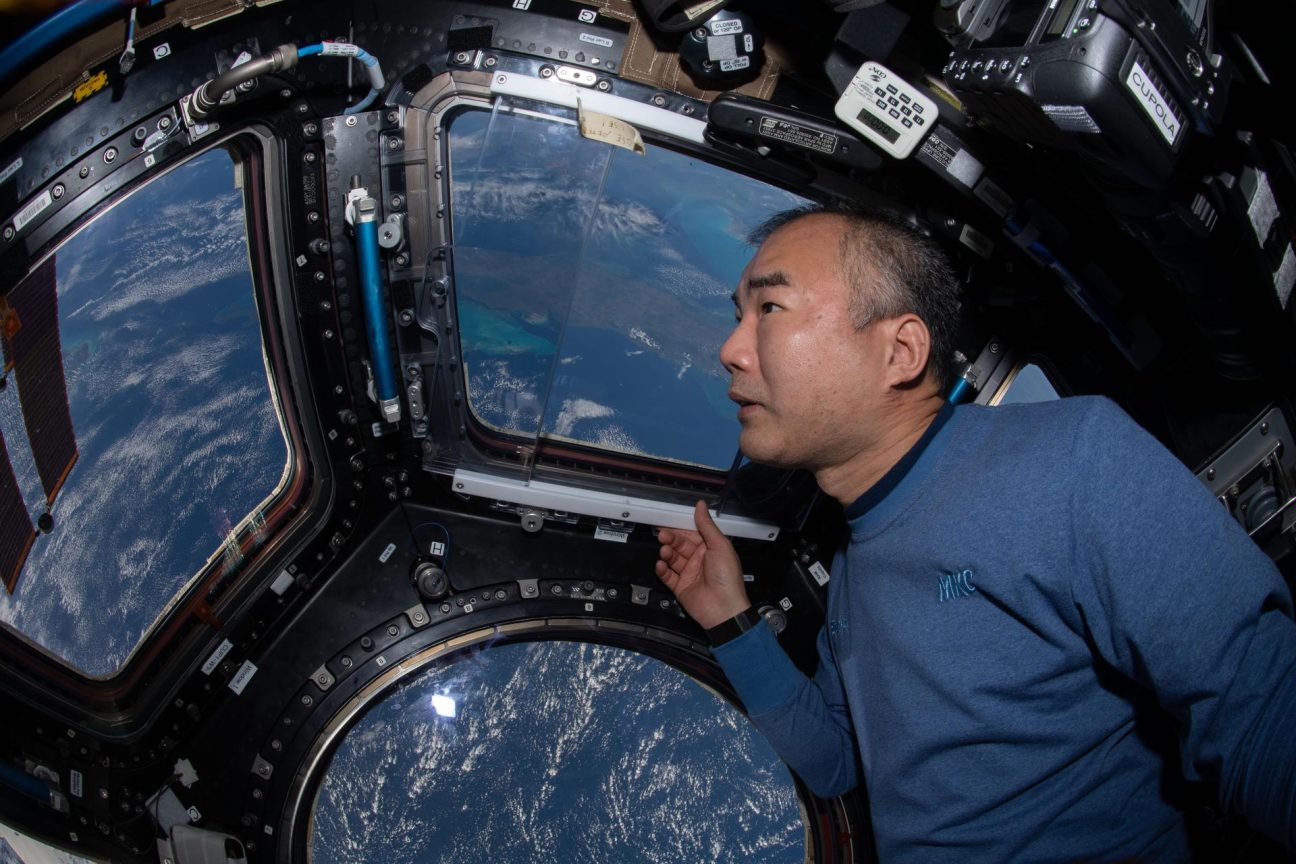

Even the ISS can’t adequately replicate a Mars journey, considering it’s about the size of a four-story house, communication is instantaneous, and the Earth is constantly in sight.

It’s for these reasons NASA is trying to learn more about how it can select astronauts who won’t only be able to endure the journey on a personal level, but also work effectively as part of a team. Using the Big 5 model of personality, researchers have developed a broad model of personality traits that seem to predict success in space.

“The suggested personality profile includes high emotional stability, moderately high to high agreeableness, moderate openness to experience with a range of acceptable scores, a range of acceptable conscientiousness scores that are above a determined minimum value, and a range of low to moderately high extraversion that avoids very high scores,” the authors wrote.

Isolation experiments conducted in the Antarctic also found that “individuals with greater resilience, adaptability, and team orientation used appropriate stress- and problem-coping strategies, allowing them to adapt to changing events, integrate successfully into a group, and function well in a team.”

Interestingly, a good sense of humor is also important.

“Humor, which stems from personality and may be influenced by cultural factors, is often cited as a benefit by spaceflight and analog teams, although sometimes it can cause friction. Crews in HERA and astronauts aboard the ISS report that appropriate affiliative humor is a key factor in crew compatibility, conflict resolution, and coping,” the authors wrote, adding that one astronaut reported in a journal that “humor and joking around continue to be huge assets and quickly defuse any problems.”

Further research needs to be conducted to better understand how space agencies can best build astronauts teams for long-term missions, the authors wrote.

“Monitoring tools with feedback mechanisms and intelligent support approaches (e.g., adaptive training) need to be developed and scientifically validated to provide data-driven technological support for spaceflight teams. These tools will enable high performing teams to succeed in the ICE environment of long-duration space exploration missions.”