What a Liberal Arts College Might Look Like in the 22nd Century

Amid all the cheering about the advent of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), another high-tech, path-breaking model in higher education is being developed in San Francisco with the help of a $25 million seed grant. Minerva University, set to admit its first class of undergraduates in 2015, bills itself as “a top-tier university built to accelerate the life trajectories of the world’s brightest and most motivated students.”

That’s rather brazen billing for an upstart, for-profit university — even one with Laurence Summers and Bob Kerrey as its marquee advisors — that has yet to matriculate a single student. In naming his school after the Roman goddess of wisdom, former Snapfish CEO Ben Nelson inverts Hegel’s teaching that the owl of Minerva takes flight only at dusk: the owl of Minerva University purports to know quite a bit in advance of the institution seeing the light of day. But that’s how entrepreneurs talk, and from what I’ve gathered, Nelson’s bold plan is based on some excellent ideas about what a liberal arts education of the next century might become.

Let’s imagine Minerva U. comes to pass along the lines Nelson has laid out. Put yourself in the shoes of one of the first students. You have been admitted solely on the basis of your academic promise, with “no weight…given to lineage, state or country of origin, athletic prowess or ability to donate.” You begin your studies in the U.S. or in your home country, and then spend semesters living in your choice of six or seven cities worldwide where Minerva has outposts. You live and learn in real time with direct human contact in classes capped at 25. Before arriving on campus, you take the equivalent of Econ 101 or Intro to Psychology online: Minerva has no lecture halls, only insanely tricked out seminar rooms linking its campuses with the most advanced technology and video connections money can buy. Your professors are top-rate scholars free of the burden of teaching massive introductory courses, excited to engage with you in higher-level, more specialized study. You pay about half the tuition you’d spend at established elite universities.

This is no MOOC-style virtual reality: no sitting in your living room with your laptop and watching slickly produced lectures by luminaries. The education is direct, intensive, personal and accountable.

But will you miss the mainstay of so much college learning: the live, in-person lecture? If your experience in college was like mine, you got a lot more out of small, discussion based courses where you were directly accountable for your work in a circle with others than you did out of large lecture courses where nobody but you knew how closely you had read the several hundred pages of assigned reading — or how much of it you had really tackled. Active note-taking and follow-up discussions may enable students to learn more from lectures, but this is decidedly not the collegiate norm. (Many students don’t even bother to show up to the lecture hall.) Mountains of educational studies show that small-scale active learning (in science, in the humanities, in dentistry) engages students much more reliably and deeply. We learn, and our lives are enriched, when we do: when we facilitate a discussion, engage in a debate, or present a paper, not so much when we sit back and listen. As Confucius wrote:

I hear and I forget

I see and I remember

I do and I understand

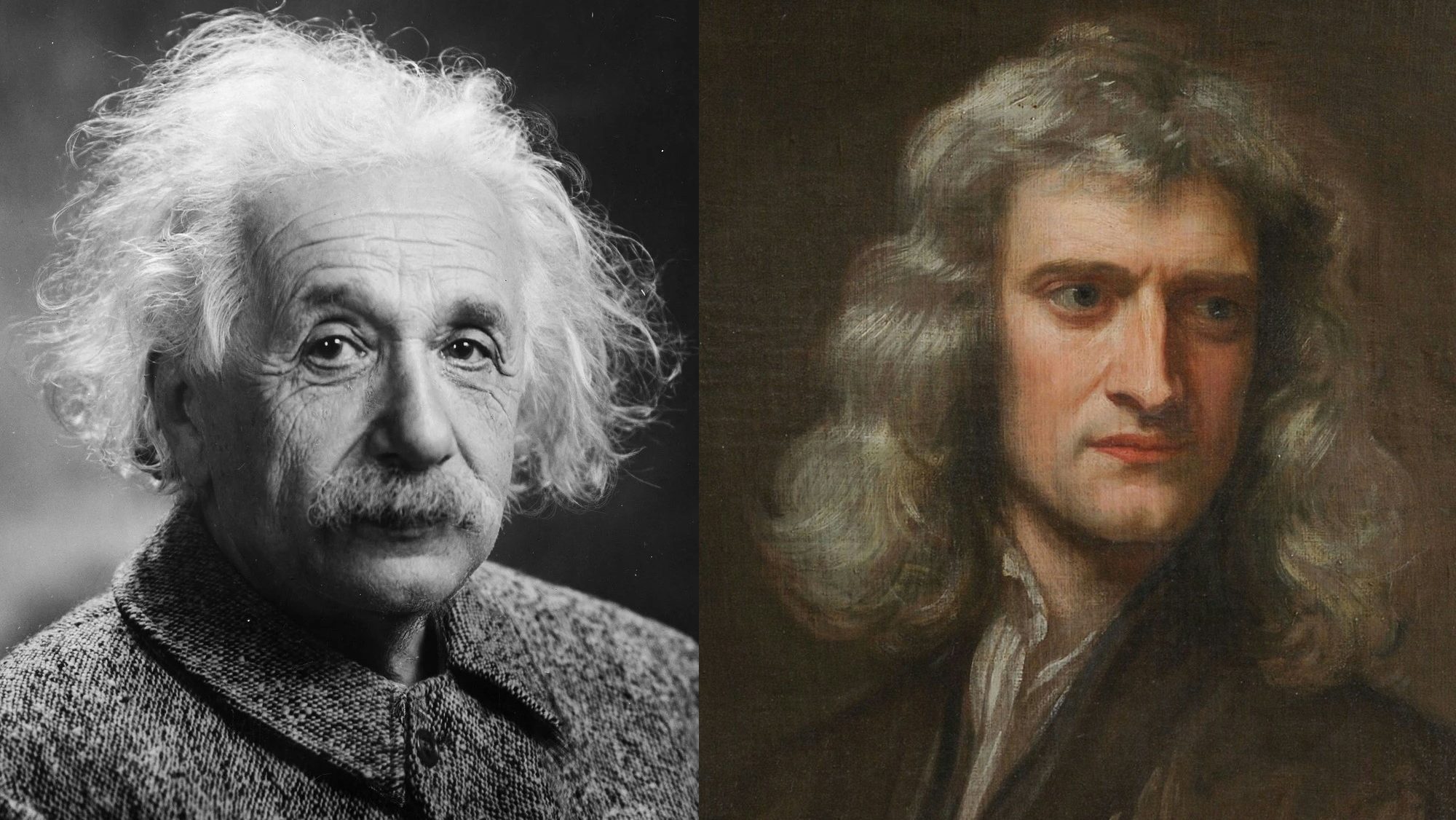

It’s not just about the medium, though. The next question is what students will be learning in the seminars. It seems this matter is still unresolved, the blanks to be filled in by four as-yet-unhired “college masters” who will lead Minerva’s four divisions (Natural Sciences, Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities and Computational Sciences) and design a yearlong “cornerstone” course that all freshmen will take. This idea draws from the concept of the core curriculum anchoring the undergraduate experience at schools like the University of Chicago, Columbia University and Bard College (where I have taught) and supercharges it, giving every first-year student the same foundation for her undergraduate studies. The idea is sure to make a student at Brown or Hampshire queasy, and some will be turned off by such a comprehensive standardized curriculum in the first year, but if the courses are great, the concept could work beautifully and ignite students’ scholarly passions. This is how Minerva explains the approach in a press release last month announcing that Stephen M. Kosslyn, a Stanford psychologist and neuroscientist, will be its founding dean:

Every aspect of the academic experience is being reimagined, including a fresh approach to the first-year curriculum. To ensure that all students begin their Minerva experience by learning the foundational skills necessary to succeed in college and professional life after graduation, all students will take the same four cornerstone courses during their first year. Case studies will form a key component of these courses, and will serve to integrate the learned material with concepts in real-world contexts. The foundational skills students develop in their first year will be drawn upon in coursework throughout the following three years of study. Students will select a concentration during the middle of their sophomore year and culminate their Minerva experience with a senior capstone project.

With students taking the same classes in several different cities and sitting down together for real-time online conversations, the concept has great potential. Imagine a unit in the Social Sciences cornerstone class on wealth inequality around the world. After reading several philosophical perspectives on the question, students could investigate the magnitude, etiology, and politics of the wealth gaps in their own societies and compare Gini coefficients, tax policy and local attitudes toward inequality. Imagine the breadth of knowledge and range of views that could come to life with this type of interaction among three or four real classrooms linked by fiber optics and widescreen monitors. Think of how rich the discussions could be.

This is mostly still in the realm of theory. I wonder how the reality of time zones will enable a 10am seminar in San Francisco to function at 1am in Shanghai or at 3am in Melbourne. I’m also unclear on how Minerva plans to scale up its educational business model while limiting class sizes to two dozen. And there are significant technological challenges associated with making this all run smoothly. But with our increasingly global 21st century making the traditional college quadrangle look a little parochial, the Minerva vision is an intriguing development.

Image credit: Shutterstock.com

Read on:

Lessons in Being Human

Kant & Cryptology at 16: Thoughts on “Academically Adrift”