Study Shows How LSD Mimics Infant’s Mind as Ego Dissolves

A groundbreaking series of experiments show how LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) alters the operation of the brain. Scientists gave LSD to 20 healthy volunteers in a specialist research center and used cutting-edge brain scanning techniques to understand what happens once the LSD is ingested.

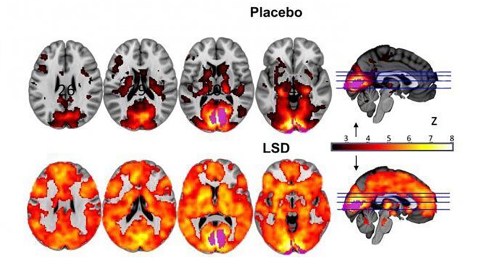

One significant finding of the experiments was that when volunteers took LSD, many parts of their brain contributed to visual processing, not just the visual cortex. They could essentially see things that weren’t there, experiencing dreamlike hallucinations.

Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, from the Department of Medicine at Imperial College London, who led the research, elaborated on this discovery:

“We observed brain changes under LSD that suggested our volunteers were ‘seeing with their eyes shut’ — albeit they were seeing things from their imagination rather than from the outside world. We saw that many more areas of the brain than normal were contributing to visual processing under LSD — even though the volunteers’ eyes were closed. Furthermore, the size of this effect correlated with volunteers’ ratings of complex, dreamlike visions. “

Dr. Carthart-Harris explained further that under LSD, people’s brain networks behave in a “unified” way, with specialized functions like vision, movement and hearing working without separation.

He said: ”Our results suggest that this effect underlies the profound altered state of consciousness that people often describe during an LSD experience. It is also related to what people sometimes call ‘ego-dissolution’, which means the normal sense of self is broken down and replaced by a sense of reconnection with themselves, others and the natural world. This experience is sometimes framed in a religious or spiritual way — and seems to be associated with improvements in well-being after the drug’s effects have subsided.”

FIG. 1: Whole-brain cerebral blood flow maps for the placebo and LSD conditions, plus the difference map (cluster-corrected, P

Interestingly, Dr. Carthart-Harris also said that the brain in the LSD state resembles the free and unconstrained brain of infancy, with its inherent hyper-emotionality and imaginative nature. He added that “our brains become more constrained and compartmentalized as we develop from infancy into adulthood, and we may become more focused and rigid in our thinking as we mature.”

It’s noteworthy that the study was crowdfunded, raising almost $80,000 from individual donations. You can see their crowdfunding pitch which explains some of their approaches here:

Additional research from the same team showed for the first time that listening to music while on LSD trigged more information to be received from the parahippocampus, which is involved in mental imagery and personal memory. The combination of music and LSD triggered complex visions in the subjects, such as evoking scenes from their lives.

The researchers hope that their findings will eventually lead to new therapies involving LSD, in particular directed at conditions with entrenched negative thought patterns such as depression or addiction. The intention is to disrupt negative patterns by employing psychedelics.

“Scientists have waited 50 years for this moment — the revealing of how LSD alters our brain biology. For the first time we can really see what’s happening in the brain during the psychedelic state, and can better understand why LSD had such a profound impact on self-awareness in users and on music and art. This could have great implications for psychiatry, and helping patients overcome conditions such as depression,” said Professor David Nutt, the senior researcher on the study and Edmond J Safra Chair in Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London.

The findings were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).