What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Art

Nothing haunts like a skeleton in the closet. When art museums and cultural institutions talk about their treasures, there are always a few items they’d rather keep out of the conversation. In Controversy 2: Pieces We Don’t Talk About, which runs through December 30, 2012 at the Ohio History Center in Columbus, Ohio, the Ohio Historical Society once again takes a few skeletons out of their closet. Focusing on five items from their archives that touch on stereotypes, the organizers don’t just dare to touch the third rail but dance along its length while inviting viewers to dance with them. By opening up the conversation about what we don’t talk about when we talk about art, Controversy 2 takes us to the dark side and sheds light not only on the pieces themselves but also on how to talk about them.

With a minimum of wall text and a maximum number of avenues of discourse, Controversy 2 challenges you to look at these five objects deeply and actively participate in the discussion rather than passively accept an official line or, even worse, the stereotype the object embodies. The most obviously controversial object is a Nazi flag captured by an American soldier at the end of World War II from a German tank and brought home to Ohio. The swastika appeared in many different cultures around the world—from Indian to Native American—long before the Nazis adopted it. White supremacist groups in the United States and abroad continue to use the swastika in the same twisted manner as the Nazis. Yet, it’s not the symbol itself but how it has been used that stirs controversy. Just when you want to apply a label of good or evil, this show makes you step back and think.

Home-grown racially charged items in the show include a poem in typescript by African-American author Paul Lawrence Dunbar written in “black” dialect, a set of toy bowling pins featuring ethnic caricatures, and a 1946 Cleveland Indians warm-up jacket with a grotesquely caricatured Native American. Ohio-born Dunbar’s “dialect” poems (including “Scamp,” the poem appearing in the exhibition) helped him become one of the first mainstream African-American poets in the late 19th century, but literary critics today focus on his non-dialect poetry, perhaps acknowledging that “dialect” was just a game Dunbar played to gain acceptance and not his true verse language. The bowling pins could double as a who’s who of early 20th century ethnic stereotypes: Middle Eastern, Scottish, African American, Native American, Italian, English, Irish, Jewish, and Asian. (The tenth pin is actually a clown, demonstrating just how seriously the makers of the set took other ethnic groups.) The baseball warm-up jacket with its garish smiling “Injun” galls even more when you realize that the current Indians’ logo isn’t much better even today.

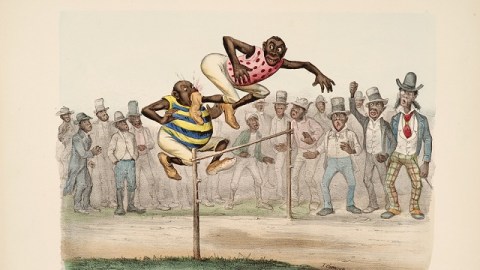

The item that set my head spinning the fastest, however, was a Currier and Ives’ lithographic print from the Darktown Series created between 1882 and 1893. The print (detail shown above) features the caption, “Darktown Athletics—A Running High Jump. Match between the darktown grasshopper and the blackville frog.” When I think Currier and Ives, I think of quaint images suitable for Christmas cards, inaccurate but charming historical scenes, and vignettes of 19th century American life, not horribly racist and dehumanizing (“grasshopper,” “frog”) caricatures of African Americans that a Klansman would cheerily collect. But there it is—a perfect reminder of the artistic skeleton in the closet. I haven’t felt this bad since seeing Dr. Seuss’ World War II era anti-Japanese cartoons.

Controversy 2 takes such bad feelings and provides outlets for channeling and talking them out. Anyone can join the conversation through Facebook or Twitter (#controversy2) and interact with the curators or other people simply looking for more information and understanding. Social media are such powerful tools for communication today that it seems a no brainer to harness that power to talk about these items that nobody wants to talk about for whatever reasons. If it seems impolite to talk about race, it’s even more impolite to ignore the racism of the past and how it lingers today in American society. If political cartoonist Mike Lester’s depiction earlier this week of President Obama as a 1970s blaxploitation-style pimp (complete with fur coat and feathered hat) as part of the Rush Limbaugh-Sandra Fluke controversy doesn’t convince you of the skeletons in our collective American visual closet, then nothing will. Controversy 2: Pieces We Don’t Talk About should start a national process of cleaning the skeletons out of the cultural closets and rattling the bones in the name of progress.

[Image:Currier and Ives. Detail of lithographic print from the Darktown Series, 1882-1893. Caption: “Darktown Athletics—A Running High Jump. Match between the darktown grasshopper and the blackville frog.” These hand-colored lithographs are part of a series created by Currier and Ives called the Darktown Series. The company made the prints between 1879 and 1893. With over 100 scenes in the theme, it was among the most popular and best-selling series that Currier and Ives produced.]

[Many thanks to the Ohio Historical Society and Sharon Dean, director of Museum and Library Services, for providing me with the image above and other materials related to Controversy 2: Pieces We Don’t Talk About, which runs through December 30, 2012 at the Ohio History Center in Columbus, Ohio.]