Soulmates: The Collaboration of Leonard Baskin and Ted Hughes

In the midst of another April’s Poetry Month, it’s worth considering how closely the sister arts of verbal poetry and visual poetry can be. The almost symbiotic relationship of British poet Ted Hughes and American artist Leonard Baskin that gave birth to beautiful, complex works such as the illustrated poetry collection Crow: From the Life and the Songs of the Crow shows just how powerful that relationship can be when the right elements are in the right place at the right time. Fortunately, photographer and documentarian Noel Chanan was also in the right place at the right time to capture this relationship for posterity in The Artist and the Poet: Leonard Baskin & Ted Hughes in Conversation 1983. In what Chanan calls “an unrehearsed dialogue” between the two friends and collaborators held one day in Baskin’s studio in 1983 when Chanan turned on a tape recorder and let the magic happen, we witness the true meaning of the term “soulmates,” in which two artistic souls in different media find common ground and inspire one another to greater heights.

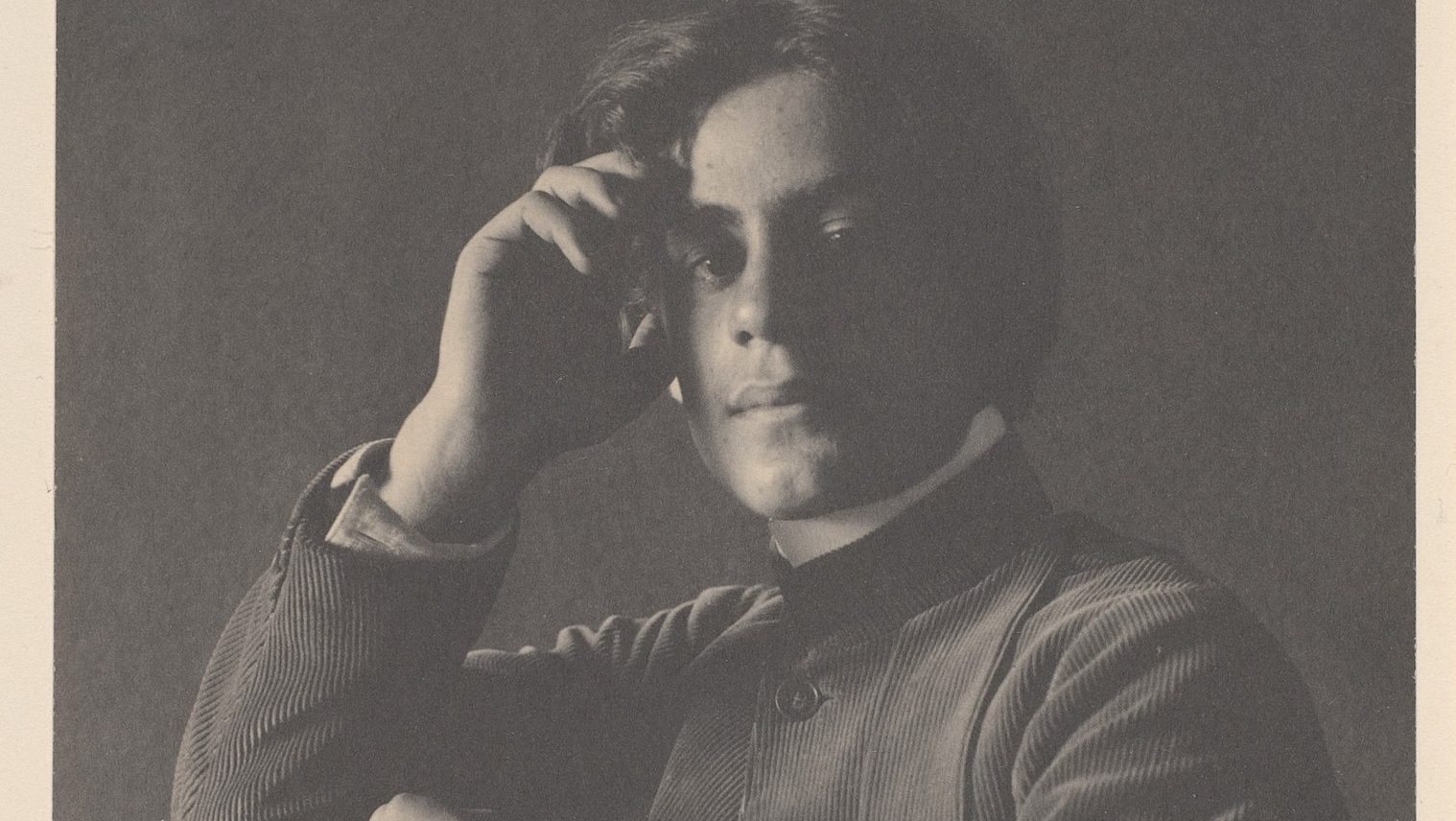

Chanan found himself a part of this magic circle of friends when he began photographing Baskin at work in his studio in 1976. At first hesitant to allow the intrusion, Baskin soon warmed to the opportunity and even began to embrace the camera’s eye. Hughes, a long-time friend, collaborator, and neighbor by that time, often dropped by the studio and allowed himself to be photographed by Chanan. (Two of Chanan’s more iconic shots of these subjects appear above.) So inspired by the discussions filling the air, Chanan convinced the two soulmates to allow him to record their musings on tape in 1983. You never get the sense that they are playing to the recording. Instead, they seem natural and real—as authentic as their true friendship. Chanan accompanies the audio (interspersed with readings of poems by Hughes) with his photographs of the two friends as well as images and sculptures by Baskin. The overall effect is as if you’re right there in the studio with them, reminiscing and musing on the world without and within.

Baskin credits the fact that both he and Hughes were “crow-haunted and death-involved” as the genesis of their collaboration on Crow. Despite coming from wildly different backgrounds, Hughes and Baskin arrived at an “affinity,” as Baskin calls it, that develops into “a relationship of presence” rather than “a relationship of influence.” Both artists are inalienably present in every work. Neither simply derives ideas from the other. Hughes imagined his crow character as a “generalized character” taking on trickster elements and other bits and pieces of mythology from all around the world. Baskin similarly saw the crow as a symbol of something despised, maybe even as an emblem of the plight of African-Americans seeking equality at the time. All of those ideas coalesced through collaboration into the illustrated poems of Crow. The illustrations, just like those Baskin later did for other collections of poems by Hughes, resist the too-common temptation to act as what Baskin derides as “visual nomenclature” for poems. Instead, they extend and illuminate the poems, standing on their own, but standing even taller for the poems they accompany.

As Hughes and Baskin recall the origins of Crow, you get a full sense of the warmth and intellectual liveliness of their relationship. Baskin speaks at one point of how crows are “fractiously alive, but despised,” only to be quickly countered by Hughes, who cites examples of crows as good luck in Chinese culture, as the bird of choice of Apollo, etc. In that single exchange you encounter both Baskin’s limitless passion and Hughes breathtaking scope of knowledge and see how those two halves bonded into a creative whole. Hughes calls this the “hidden, telepathic level” of great collaborations. Chanan’s documentary does it’s very best at uncovering that hidden power.

“Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments,” wrote Shakespeare. In the marriage of these two true minds of Hughes and Baskin, there are seemingly no impediments to collaboration. (One wonders what thoughts they shared regarding Hughes’ wife Sylvia Plath, who knew Baskin and even dedicated the poem “Sculptor” to him, but do not share in this conversation.) The Artist and the Poet: Leonard Baskin & Ted Hughes in Conversation 1983 should serve as a template for how collaborations should work and how to be the best soulmate you can be.

[Images: (Left) Ted Hughes in Leonard Baskin’s studio, Devon, England, 1979, © Noel Chanan. (Right) Leonard Baskin, Northampton, Mass., 1991 © Noel Chanan.]

[Many thanks to Noel Chanan for providing the images above and a review copy of The Artist and the Poet: Leonard Baskin & Ted Hughes in Conversation 1983.]