Man’s Final Lore: How Shakespeare Shot Lincoln

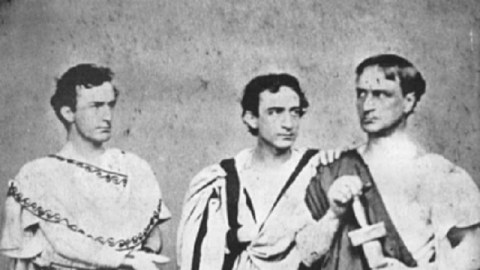

It’s one of the most infamous images of American Shakespearean theater. Taken from a performance of Julius Caesar in New York City in 1864, the photograph shows three brothers from a distinguished acting family pose in character: Junius as Cassius on the right, Edwin as Brutus in the center, and on the left, as Marc Anthony, the youngest brother, John Wilkes Booth. It was the only time the three brothers appeared together on stage, but that play would haunt them the rest of their lives. John Wilkes watched his brother Edwin’s portrayal of the “noblest Roman of them all” and decided to become an “American Brutus” who would slay the tyrant Abraham Lincoln who waged a Civil War against his beloved South. Today is the anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 by the would-be Brutus, who failed to recognize the tragic flaw of hubris Shakespeare gave to the protagonist of Julius Caesar. Shakespeare didn’t pull the trigger, of course, but it was his play that inadvertently triggered a series of events that inspired the act.

Everyone who remembers Julius Caesar from high school also remembers that the title character is not the hero of the play. It’s the trials and tribulations of Brutus we watch until the final act. Brutus takes in the false praise of Cassius and the other conspirators and lends his good name and reputation to sweeten the foul murder. That good name and reputation echoes throughout the play until Marc Anthony’s famous speech calling “Friends, Romans, Countrymen…” In Marc Anthony’s mouth the repeated “and surely Brutus is an honorable man…” rings more and more hollowly. And, yet, John Wilkes Booth failed to hear that hollow ring and its deeper meaning despite declaiming the words on stage. For him, Brutus remained an ideal to emulate.

Once that fateful shot was fired, life for all the Booths changed. Edwin, perhaps the greatest Shakespearean actor in America at the time, never shook the specter of his brother’s actions. Edwin actually supported the Northern cause and voted for Lincoln, despite John Wilkes protestations that Lincoln would soon crown himself king. Even the fact that Edwin had saved the life of Lincoln’s son Robert in 1864 provided little solace. The quintessential Hamlet of his age, Edwin felt the ghosts of the past pursuing him to the grave.

Shortly after Lincoln’s assassination, Herman Melville viewed an art exhibition at the National Academy in New York City. Among the works shown was Sanford Gifford’s A Coming Storm (now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art). Noticing that Edwin Booth owned the painting, Melville found a deeper significance in the foreboding landscape. In the poem “The Coming Storm,” Melville connected that landscape to the psychic landscape of Edwin Booth:

A demon-cloud like the mountain one

Burst on a spirit as mild

As this urned lake, the home of shades.

But Shakspeare’s pensive child

Never the lines had lightly scanned,

Steeped in fable, steeped in fate;

The Hamlet in his heart was ‘ware,

Such hearts can antedate.

Melville saw the “Hamlet” in Edwin’s heart through his choice to purchase Gifford’s painting. In essence, allowing the painting to exhibit was Edwin’s public statement on the assassination—a deep sadness mixed with a realization of the same human failings Shakespeare wrote of over and over. Melville finishes the poem with the following lines:

No utter surprise can come to him

Who reaches Shakspeare’s core;

That which we seek and shun is there—

Man’s final lore.

For Edwin, Melville, Gifford, and Shakespeare, “Man’s final lore”—the last lines of the story we write with our actions—is what we both “seek and shun” in human nature. As Edwin well knew, Shakespeare has Hamlet say, “What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals—and yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me…” The paradox of angelic and barbaric in humanity vexed Edwin, especially when his brother became the embodiment of betrayal. John Wilkes Booth, a Brutus wanna be, scanned Shakespeare’s lines too lightly seeking justification for his own desires and was genuinely shocked at the negative public reaction to his act. If anything good can come of remembering the assassination of Lincoln, it is the lesson that we fail to read Shakespeare, or dare to misread him, at our peril.